EDitorial Comments

Windy City 2020 Film Program Notes 1

At each year’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention, Murania Press sponsors a film program that concentrates exclusively on movies adapted from stories originally published in pulp magazines. This is the con’s 20th year, and the 19th for our film screenings. Below are program notes describing the Friday offerings; tomorrow we’ll post notes covering Saturday’s selection.

FRIDAY

12:00 pm — The Roaring West (1935), Chapters One through Eight, 160 mins.

Adapted from Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, January 1935).

Buck Jones, who had been a Western star for 15 years when he made Roaring West, was also an avid reader of pulp fiction. During his 1934-37 tenure at Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures, Buck had his own production unit and personally selected the stories for his starring vehicles. The vast majority were yarns first published in rough-paper magazines. We have not read Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law,” the credited source for The Roaring West, and therefore can’t comment on the serial’s degree of fidelity to the original story. But very few novels had plots dense enough to fill 15 two-reel episodes, and it’s obvious that screenwriters George H. Plympton, Nate Gatzert, Basil Dickey, Robert Rothafel, and Ella O’Neill added numerous capture-and-escape sequences to pad the proceedings.

Jones plays Montana Larkin, a two-fisted cowboy who helps his pal Jinglebob Morgan (Frank McGlynn Sr.) rescue the latter’s brother Clem (Harlan Knight) from claim jumpers led by Gil Gillespie (Walter Miller). The bad guys are eager to learn the location of Morgan’s gold mine. Montana’s allies include prominent rancher Jim Parker (William Desmond) and his daughter Mary (Muriel Evans).

Some Windy City viewers might find Roaring West unnecessarily repetitive, although it should be remembered that serial chapters were designed to be seen at the rate of one per week, not bunched together in groups of seven or eight per day. But the chapter play’s plot deficiencies are compensated for by a wealth of fast action and Buck’s endearing performance. He’s especially good in scenes with Muriel Evans, his favorite leading lady, who also appeared in six of his self-produced feature films. Their chemistry is palpable and authentic; when I met Muriel in 1990 and asked her about Jones, she described him as “one of God’s great gentlemen.”

At the time of this serial’s production Buck Jones was the nation’s top cowboy star, a favorite of exhibitors and hero to millions of American boys. The Roaring West isn’t the best of his motion pictures by a long shot, but it’s representative of his peak-period output and rollicking good fun even today, 85 years after its theatrical release. We can guarantee that it won’t tax your brain, so if looking to take a break from the dealer room’s hustle and bustle, you could do a lot worse than to relax by watching a few chapters.

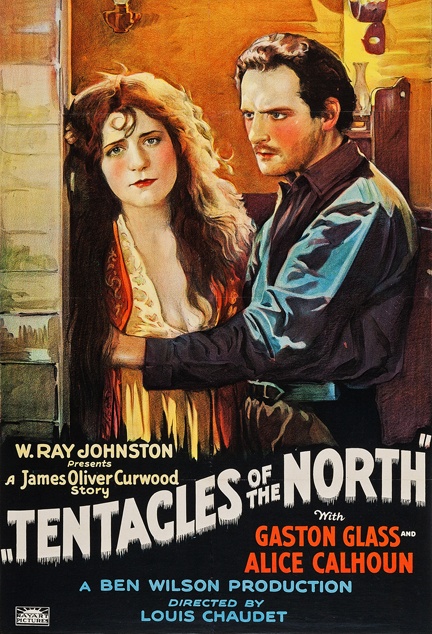

02:45 pm — Tentacles of the North (1926), 52 mins.

Adapted from James Oliver Curwood’s “In the Tentacles of the North” (Blue Book, January 1915).

Few fictioneers ever attained the success enjoyed by James Oliver Curwood, who wrote for slicks and pulps alike and saw many of his best tales published between hard covers. His virile adventure stories, mostly taking place in Alaska and the Canadian Northwest, were extremely popular with filmmakers, who began licensing them in 1910 and adapted them to the screen regularly for the next 50 years. Some Curwood yarns, including River’s End, The Wolf Hunters, and Back to God’s Country, were made into movies three and four times each. For many years, especially during the Twenties and Thirties, his name on a movie poster virtually guaranteed an audience regardless of the film’s quality.

This low-budget thriller, while hardly among the best Curwood-based movies, is certainly typical of the breed. A terse synopsis from Motion Picture News captures its essence nicely: “Ice in North seas ties up two vessels; one with boy mate and other with daughter of seaman left alone through death of crew. Boy leaves his ship and discovers girl. He is chased by his crew but outwits them and escapes both them and the Arctic wastes. He brings girl back to civilization.”

Produced by Poverty Row habitué Ben Wilson, Tentacles of the North hews closely to the Blue Book yarn on which it’s based and seems to have pleased the undiscriminating small-town audiences for which it was intended. The unabashed melodrama wasn’t very well received by big-city sophisticates, though. Variety‘s critic “Mark” (no last name given), reviewing the picture after a screening in Manhattan, was decidedly unimpressed: “It may have been the intention to make this Curwood [adaptation] a big production, but it pulled a smashing dud, face down. Little to commend it despite the apparent camera effort to make the far, far northland, but the icy, frigid scenes won’t. [sic] The New York audience didn’t think much of it. Some of them sighed when the end came. One wonders if Mr. Curwood could recognize in this production any of the realistic scenes his book [sic] describes.”

On the plus side, we are showing a privately pressed DVD mastered from an original tinted 35mm nitrate print of Tentacles. As always with the silent movies we include in our Windy City film program, it’s accompanied by a period-appropriate music score.

03:45 pm — The Working Man (1933), 75 mins.

Adapted from Edgar Franklin’s “The Adopted Father” (All-Story Weekly, January 22—February 19, 1916).

Totally forgotten by even the most rabid fans and collectors of pulp magazines, Edgar Franklin (real name: Edgar Franklin Stearns) for many years was a ubiquitous presence in the Munsey sheets—Argosy, Cavalier, All-Story, Scrap Book, Railroad Man’s Magazine—and sold frequently to other general-interest pulps such as People’s, Blue Book, and The Popular Magazine. His work also appeared regularly in such prestigious slicks as Red Book, Hearst’s Cosmopolitan, and the mighty Saturday Evening Post. So why is Franklin so little known today? Mostly because he specialized in humorous tales with domestic settings and not gun-dummy Westerns, lost-race adventures, or masked-hero melodramas—in other words, not the types of stories favored by most present-day collectors.

Franklin’s stories were licensed by Hollywood studios some 32 times between 1914 and 1938, although elements from the best were “borrowed” rather promiscuously by scripters cranking out purportedly original screenplays. His 1916 book-length comedy-romance “The Adopted Father” was filmed three times: in 1924 as $20 a Week, in 1933 as The Working Man, and finally in 1936 as Everybody’s Old Man. The first two versions starred stage actor George Arliss, a horse-faced ham who reinvigorated his film career with a series of well-regarded early-Thirties biopics that cast him as Voltaire, Disraeli, Cardinal Richelieu, Alexander Hamilton, and the Duke of Wellington. A scenery-chewer of the first water, Arliss occasionally eschewed heavy historical fare in favor of lighthearted contemporary tales that permitted him to portray avuncular characters.

The Working Man casts Arliss as wealthy shoe manufacturer John Reeves, who leaves his business in the hands of ambitious nephew Benjamin Burnett (Hardie Albright) and goes to Maine on a fishing trip. While up there Reeves meets Tommy and Jenny Hartland (Theodore Newton and Bette Davis), the fully grown but undisciplined children of his friendly rival, the late Tom Hartland. Distressed by their cavalier handling of the family business, Reeves has himself appointed a trustee of the Hartland estate. He insinuates himself into the lives of Tommy and Jenny—who don’t know his true identity—and persuades them to take greater interest in the venerable firm that is their father’s legacy. Jenny becomes sufficiently competitive to secure a job at the Reeves Company under an assumed name, but she doesn’t count on falling in love with John’s nephew Benjamin. As the saying goes, complications ensue.

Working under his favorite director, John G. Adolfi, Arliss turns in a delightful performance. Bette Davis, still a year away from her star-making turn in Of Human Bondage (1934), is appropriately spirited as Jenny Hartland; it’s hard to imagine that Working Man audiences wouldn’t have recognized the obvious talent that would soon make her one of the biggest names in the picture business. Fast-faced and funny, this Warner Bros. programmer is easily the best adaptation of Franklin’s thrice-filmed 1916 pulp story.

Immediately Following Auction — Lawless Valley (1938), 59 mins.

Adapted from W. C. Tuttle’s “No Law in Shadow Valley” (Argosy, September 26, 1936).

A phenomenally prolific pulpster whose Westerns appeared in rough-paper magazines for more than 40 years, Tuttle also enjoyed considerable success in Hollywood. Movie rights to his yarns were being snapped up by studios as early as 1920, and during the silent-film era he penned original screen stories for such popular cowboy stars as Hoot Gibson. One of his pulp tales, “Sir Piegan Passes,” was adapted by filmmakers three times.

Tuttle’s 1936 novelette “No Law in Shadow Valley” was licensed early in 1938 by RKO, at that time on the lookout for properties that would make suitable vehicles for its newest Western star, George O’Brien. No stranger to horse operas adapted from pulp stories, O’Brien at Fox Film Corporation during the early Thirties had top-lined sturdily made Westerns based on popular yarns by Zane Grey and Max Brand. Budgets routinely approached $200,000 and funded lengthy sojourns to picturesque locations in Arizona, Colorado, and Utah.

O’Brien’s RKO series, however, was produced on a more modest scale. Lawless Valley, which opened the 1938-39 season, cost exactly $80,364 with exteriors lensed in familiar Southern California locations and on the Western street in the studio’s Encino facility. A strong entry, it has a dialogue-heavy first act but picks up the pace considerably about 30 minutes in, finishing with the knuckle-bruising action that audiences had come to expect from George’s pictures. The brawny star plays an ex-con who returns to his home range to apprehend the men responsible for killing his father and framing him into prison. Forbidden from carrying a gun by the terms of his parole, O’Brien’s character is forced to rely on his wits to expose the real culprits.

In a nice bit of casting, veteran heavy Fred Kohler and his son Fred Jr. play a crooked father and his offspring. Chill Wills, rail-thin at this early stage in his film career, interprets a familiar Tuttle character type: the lanky, disrespectful deputy who’s forever needling a blustery sheriff. Erstwhile silent-serial leading man Walter Miller contributes a solid supporting turn as a tramp who befriends O’Brien after the latter is released from prison.

Nobody will ever mistake Lawless Valley for Shane, Stagecoach, or The Searchers. It’s a Saturday-matinee “B” Western, plain and simple, but a first rate example of the species. If you’re not expecting too much we think you’ll thoroughly enjoy this encore presentation from our 2002 lineup.

One thought on “Windy City 2020 Film Program Notes 1”

Leave a Reply to Al Stone Cancel reply

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net

Enjoyed the writeups. Makes me wish I was going.