EDitorial Comments

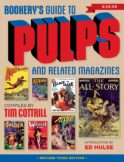

Vintage Pulps Added to Collectibles Page

I’ve just added a dozen or so pulps to the Collectibles page, including a handful with stories by the late great Ray Bradbury. Half of them are science fiction, but you’ll also find Western, fantasy, detective, and general-adventure magazines for sale. Pretty good stuff, if I do say so myself.

I’ll be listing a few cherce pieces tomorrow, among them some rare vintage hardcovers and paperbacks. Check the Collectibles page often; I guarantee you’ll regularly find real bargains there.

Update: Just as I was typing the above sentence, two pulps were purchased. See, you gotta act fast if you want to score the best items!

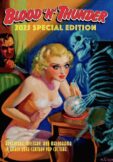

It’s Now Easier to Start or Renew Your BLOOD ‘N’ THUNDER Subscription

As some of you know, the Murania Press site was in development quite a while, with work conducted in fits and starts. Chris Kalb came up with the basic design for what began as a Blood ‘n’ Thunder site, but after launching the “Classic Pulp Reprints” line last year I decided to put all my publications under the Murania umbrella. Chris and I made several major changes and ironed out numerous glitches before actually getting the site up and running a couple weeks ago.

I guess we were bound to miss something, and some of our earliest visitors picked up on it. Great site, one told me by e-mail, but where do you sign up for a subscription? Within four days of going on line I’d received a handful of similarly worded comments. So this weekend I finally asked Chris to add a Subscribe link to the Shopping Cart feature, which he did today. You can find it at the bottom of the Blood ‘n’ Thunder page. Or, if you’re really lazy, you can click here.

As the blurb says, it actually does pay to subscribe rather than buy issues one at a time. Single-copy price is $11.95, and I have to add two bucks more for shipping. At fourteen bucks per, you’re paying $56.00 for the full yearly complement of four issues. If you subscribe, you get all four for $40.00 — and that includes shipping. Ten bucks an issue versus fourteen. It should be a no-brainer.

Now is a particularly good time to re-up or subscribe for the first time. The upcoming Summer 2012 number is our jumbo-sized Tenth Anniversary Special. It will be half again as large as the average issue (which runs 110 pages, give or take a couple) and bear a single-copy price of $14.95. The extra weight will increase the cost of shipping to nearly three dollars. But to subscribers it’ll be just another issue, worth the same ten bucks out of forty you pay for a year’s worth.

The Tenth Anniversary Special — about which you’ll be reading more in weeks to come — debuts at this year’s PulpFest. By renewing or subscribing for the first time now, you won’t risk missing it at the bargain price.

Looking Ahead to PulpFest

I’ve just returned from New York City, where my day’s activities included attending a four-hour meeting of the Gotham Pulp Collectors Club. The group assembles at a library in downtown Manhattan on the second Saturday of every month, and members can always count on a lively time. Some of us continue to gab during lengthy after-sessions at a nearby Dunkin Donuts. The conversations are dominated — but not monopolized — by hobby talk, with attendees showing off new acquisitions, weighing in on stories they’ve recently read, and commenting on special events such as auctions, conventions, and pulp-art exhibitions.

At today’s meeting we discussed the upcoming PulpFest, now just a scant nine weeks away. I could overstate the case by reporting that GPCC members were breathless with anticipation, but let’s just say those who plan on making the trip to Columbus are looking forward to our first confab in a new venue: the Hyatt Regency Hotel, located in the middle of the bustling downtown area. Those of us on the committee are especially excited to be moving to larger and more luxurious digs, given the steady deterioration of our previous home. The Hyatt Regency recently completed a $12 million refurbishment of its guest rooms, adding WiFi access, iHome Stereo with iPod docking access, and other amenities commensurate with the hotel’s size and stature. We’re quite confident you’ll find it an extremely convenient and comfortable venue.

I won’t waste space here repeating information you can find easily on the PulpFest site linked to above, but if you’re at all interested in coming — as either a fan or a vendor — you should make reservations soon. Our hucksters room at the Hyatt is larger than the one we had at the Ramada, but dealer space is going rapidly, so potential exhibitors should get in touch as soon as possible. I know that most wall tables are already spoken for, and a majority of island tables as well. If the pace of last year’s bookings is any guide, the entire room will be filled within the next four, maybe five weeks. Since PulpFest is a little later this year than was previously the case, you’ve got extra time to finalize your plans — but not much extra time.

Attendance-wise, this year’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention was another record-breaker, notwithstanding the still-sluggish economy. We’re hoping to draw an equally big crowd. Interest in pulp fiction continues to grow, fueled by a seemingly inexhaustible supply of reprints, newly written works in the classic tradition, and surprising strength of demand for the vintage magazines themselves. The recent Adventure House auctions of pulps owned by noted SF writer Frank Robinson have generated record-shattering prices, and PulpFest is nothing if not Nirvana for collectors of rough-paper rarities.

If you’ve attended our convention before, you know what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, you owe it to yourself to visit us at least once (and this is the year to do it, as a cursory glance at our guest-star lineup and schedule of activities demonstrates). And if you already plan on coming but haven’t made your reservations…well, what are you waiting for, an engraved invitation?

FIRE-TONGUE: Not So Hot.

For me, Sax Rohmer novels (along with those of Edgar Wallace, Erle Stanley Gardner, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and a half dozen other authors I could name) are the literary equivalents of comfort food: easy to digest, easy on the palate, and full of familiar flavor. Every now and then, though, I devour one that just doesn’t satisfy. Fire-Tongue (1921), which I recently consumed, actually left a bad taste in my mouth.

Published in England by Cassells and serialized here in Collier’s prior to being issued in hard covers by Doubleday, Page & Company, Fire-Tongue continues the adventures of a minor Rohmer hero, London-based private investigator Paul Harley, whom we’re told has had considerable success solving bizarre crimes and is “the last court of appeal to which Home Office and Foreign Office alike came in troubled times.” In other words, he’s Nayland Smith without the earlobe-tugging and nervous energy.

As the story opens Harley is visited in his Chancery Lane office by Sir Charles Abingdon, a prominent surgeon whose background includes a lengthy stint in the Orient. He tells the detective that his life is in danger but, characteristically for a Rohmer novel, seems curiously unwilling to unburden himself fully at the outset. Nonetheless, Harley agrees to help and promises to join Sir Charles at home that evening for a full explanation.

Abingdon is convinced that he’s being watched and followed constantly, and the investigator gets the same feeling as he approaches the surgeon’s residence. Rohmer explains that Harley has a sixth sense, which alerts him to the presence of potential danger: “It was an evasive, fickle thing, but was nevertheless the attribute which had made him an investigator of genius.”

There’s more beating around the bush when Sir Charles welcomes Harley into his home—which, not unexpectedly, is furnished in Oriental style. (One can be forgiven for believing that all Rohmer characters patronize the same curio shop.) Later, without having explained much at all, the surgeon has some sort of seizure and collapses. His last words are “Fire-Tongue…Nicol Brinn.”

Twenty-seven pages into the novel, we don’t know a whole lot more than we did at the beginning. Abingdon has a beautiful daughter named Phyllis (referred to throughout the yarn, somewhat annoyingly, as “Phil”), who enjoys the friendship of a handsome Persian named Ormuz Khan. Sir Charles distrusted this man, perhaps owing to a conviction that his recent problems and general unease had their origins in the East.

Nicol Brinn proves to be a charismatic American adventurer with a tragic secret, well known for having courted and cheated death repeatedly with a series of sensational exploits. He, too, has had strange experiences in the East and shares Abingdon’s reluctance to reveal anything that could help clear up the mystery of the surgeon’s sudden death, eventually revealed as the by-product of a subtle, cleverly administered poison.

Following the death of Sir Charles, nothing of significance occurs in Fire-Tongue for more than a hundred pages. Rohmer serves up plenty of atmospherics but few characters and little plot development. Halfway through the 304-page Doubleday edition I got the distinct impression that he began the story with little or no idea where it was headed, that he made it up as he went along. Even though Paul Harley has been established as the protagonist, it’s Nicol Brinn who comes to dominate the story.

Not surprisingly, this “Fire-Tongue” is our friend Ormuz Khan, who secretly heads an Oriental cult determined to unite the forces of the East and wreak havoc on the West. But he’s a singularly ineffectual menace: Aside from capturing Phyllis Abingdon and Paul Harley (whose vaunted intuition fails him miserably), Fire-Tongue utterly fails to accomplish anything worthy of note. Brinn’s tragic secret turns out to be his love for the novel’s femme fatale, Naida, who is dispatched without prejudice by Ormuz Khan once he learns she’s been playing footsie with the American.

Not surprisingly, this “Fire-Tongue” is our friend Ormuz Khan, who secretly heads an Oriental cult determined to unite the forces of the East and wreak havoc on the West. But he’s a singularly ineffectual menace: Aside from capturing Phyllis Abingdon and Paul Harley (whose vaunted intuition fails him miserably), Fire-Tongue utterly fails to accomplish anything worthy of note. Brinn’s tragic secret turns out to be his love for the novel’s femme fatale, Naida, who is dispatched without prejudice by Ormuz Khan once he learns she’s been playing footsie with the American.

In a brief, perfunctory, and wholly disappointing climax, Fire-Tongue abandons his headquarters and is hotly pursued by Harley and Brinn, who crash their car into his. The big chase lasts all of two short paragraphs. Ormuz Khan is killed in the crack-up and Harley is taken to hospital with minor injuries.

The novel’s last 36 pages—more than a tenth of its total wordage—are devoted to a laborious explanation by Nicol Brinn of Fire-Tongue’s origin and miraculous powers (which have amounted to little more than an ability to produce flame at will—a simple magic trick). The American adventurer, we learn, used his well-publicized trip to Tibet as an excuse to search for the fabled Temple of Fire—where, according to ancient prophesy, a second Zoroaster was about to appear to “redeem and revolutionize the world” and “preach the doctrine of eternal fire.” Brinn found the place, learned that Ormuz Khan had set himself up as the Master, and fell in love with Naida, one of Fire-Tongue’s followers.

In this novel Rohmer gives the reader a big build-up but lets him down badly. Put succinctly, the yarn lacks punch. The enigmatic Fire-Tongue and his followers are, quite unintentionally I’m sure, revealed as bunglers; my sense was that the whole bunch wouldn’t have lasted a single round in the ring with one of Fu Manchu’s dacoits. And the sublimely intuitive Paul Harley reminds me of Hallorann, the old caretaker played by Scatman Crothers in the movie version of Stephen King’s The Shining. Remember him? Hallorann has the psychic ability to “see” things unfolding hundreds of miles away, but he can’t tell that Jack Nicholson’s Torrance is waiting around the corner to bury an ax in his chest. Rohmer wastes hundreds, maybe thousands of words describing Harley’s sensitivity to dangerous surroundings and occult phenomena, but his ostensible protagonist is captured by Fire-Tongue’s minions with laughable ease, leaving a supporting character to perform the story’s nominal heroics. Phooey.

Bottom line: About the only thing Fire-Tongue did was burn me up.

DON WINSLOW OF THE NAVY: Finally, a Good-Looking DVD!

Props to the good people at Hermitage Hill Media for their new, bargain-priced DVD edition of Don Winslow of the Navy, a 1942 Universal serial based on the once-popular comic strip by Frank V. Martinek and Leon Beroth. It features brawny, iron-jawed Don Terry as the intrepid Winslow, Walter Sande as Don’s sidekick Red Pennington, Claire Dodd as love interest Mercedes Colby, and Kurt Katch as the strip’s principal villain, The Scorpion. Shot in the fall of 1941 with scenes laid in and around Pearl Harbor, this well-remembered chapter play anticipates impending conflict with the Axis powers without naming names, as was Hollywood’s habit in the months leading up to our entry into World War II. There’s more than a little stock footage of America’s mighty fleet (before much of it was destroyed on December 7, 1941), but also plenty of action. Serial fans have joked for years that Winslow is one of the most ineffective scrappers in chapter-play history because he seems to lose every fight — and there are plenty of them. But that hasn’t prevented the serial community from lamenting the unavailability of a high-quality video transfer.

Existing 16mm prints of Don Winslow of the Navy, struck for non-theatrical use and early TV syndication, are not particularly crisp, and the jury-rigged transfer systems employed by bootleggers aren’t capable of yielding a sharp, properly timed image. Hermitage Hill has made something of a speciality of working with problem prints of rare serials to come up with more-than-acceptable transfers, and frame-by-frame comparison of their Winslow with others shows that they’ve hit pay dirt again. It doesn’t look as good as commercial DVD releases mastered from pristine 35mm film elements (such as master positives struck from the original camera negatives), but it’s clearly superior to anything video-era serial buffs have seen to date on this title. Moreover, you can’t beat Hermitage Hill’s prices and service. Highly recommended!

Ray Bradbury, R.I.P.

I’ve just read that Ray Bradbury died this morning in Los Angeles at the age of 91. He had been in failing health for several years now, but he never lost his zest for life or his enthusiasm for the genre he helped shape. I imagine most folks today remember Ray for his SF works, including The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451, but in his salad days as a penny-a-word pulpster he turned out some terrific fantasy and horror stories for Weird Tales and some neat mystery yarns for Popular Publications’ detective mags.

I don’t have the time or, frankly, the knowledge to do Bradbury justice here, so I’ll just say that his loss is a major one — not only to science fiction, but to American popular culture in general.

I’ll try to put a more fitting tribute together for Blood ‘n’ Thunder‘s Summer issue. Anyone with ideas along those lines, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with me.

Hoppy birthday, William Boyd: Part 2

The first series entry, Hop-a-long Cassidy, was released on August 23, 1935. Within weeks it was playing in thousands of theaters, most of them owned by Paramount. Reviews were positive but not especially enthusiastic; Variety, for example, called the film “not overly exciting” but allowed that it “moves along smoothly, without going in too heavily for usual horse-opera dramatics.” Nonetheless, the movie-going public immediately took to Hoppy – who, by the way, earned his nickname in the third reel by catching a bone-shattering bullet in the leg while rescuing his fellow Bar 20 puncher, hotheaded young Johnny Nelson (played by James Ellison).

Below you’ll find a couple photos taken at the Lubkin Ranch in Lone Pine, California, during production of Hop-a-long Cassidy. I realize the image quality isn’t great, but bear in mind that the scans were made from small snapshots and then blown up. You can view them at a somewhat larger size by clicking on them. These pictures have never been published, by the way. (Readers of this blog can count on seeing such rarities from time to time, so come back often.)

When the first six films proved successful, Paramount brought the series in house, increasing the budgets and paying Harry Sherman a salary while giving him complete autonomy to produce the pictures as he saw fit. The studio released six Hopalong Cassidy Westerns per “season” (the period beginning roughly around Labor Day and extending through the following year’s Memorial Day) until 1942, when distribution of the series was transferred to United Artists, at that time suffering an acute product shortage.

His career reinvigorated, Boyd initially resisted being typed as a “B”-Western star but eventually accepted the new reality. He got his personal life in order too, divorcing fourth wife and drinking buddy Dorothy Sebastian in 1936 and marrying Paramount contract player Grace Bradley the following year.

Grace had developed a schoolgirl crush on William Boyd after seeing The Yankee Clipper (1927), one of his DeMille-produced PDC films. The Brooklyn-born Bradley was still a teenager – and a stunningly beautiful one at that – when she entered show business herself, performing in Broadway musicals and coming to Hollywood in 1933 as a Paramount contractee. She still adored Bill Boyd, even after the scandal that cost him his RKO contract.

Upon learning this, Boyd asked the star-struck actress on a date in early May of 1937. (When he called Grace at home, she initially balked, convinced that he was an imposter put up to phone her as a gag.) The ensuing whirlwind courtship culminated in their marriage on the fifth of June – Bill’s birthday – exactly 75 years ago yesterday. None of Boyd’s previous four unions lasted more than six years, but Grace stuck by him through good times and bad. Their storybook romance ended only with his death in 1972, after 35 years together.

Grace is credited with keeping Bill on the straight and narrow. He never entirely gave up drinking, but she kept him from going off the rails, even when he became depressed after Harry Sherman stopped producing the Hopalong Cassidy Westerns in 1944. By that time Bill had played his slicked-down version of Clarence Mulford’s rough-hewn cowboy hero in 54 feature-length movies. He doubted any producer in Hollywood would ever cast him in another role.

Scraping together every last dollar, Boyd bought out his old producer, who had retained a financial interest in the character. Then he renewed Sherman’s distribution deal with United Artists and produced another dozen Hopalong Cassidy films for theatrical distribution, six for 1946-47 and six for 1947-48. Bill tried to freshen up the series by changing sidekicks, injecting strong mystery elements, and even discarding his trademark black outfit. But his self-produced Hoppy entries, lacking verve and panache, failed to reap box-office rewards.

Broke again, his feature-film career over, William Boyd turned to a new medium called television. The big studios were initially constrained from releasing their libraries to TV by the complaints of exhibitors, who feared movie fans would quit going to theaters if they could get major Hollywood motion pictures in their homes on the small screen. In the late Forties and early Fifties, product-hungry commercial stations were programming old, independently made American “B” movies and British imports. So, in 1949, Boyd licensed the first 54 Hopalong Cassidy Westerns – his self-produced efforts were still making their theatrical rounds – to the NBC network, which aired them in prime time.

A new generation of youngsters discovered Hoppy via TV, and within a couple years Bill was back on top. Cannily but carefully, he doled out limited-term rights for a slew of licensed products featuring Hopalong Cassidy. His image appeared on shirts, pajamas, blankets, lunch pails, pocket knives, coloring books – just about every kid-oriented consumer product you can imagine. In 1952 he produced a half-hour series for network broadcast. The first 12 episodes were cutdowns of Bill’s 1946-48 features; the remainder found him once again in the familiar black outfit with well-known character actor Edgar Buchanan playing Cassidy’s saddle pal Red Connors. That same year he briefly went back to work for his old mentor, Cecil B. DeMille, making a cameo in the latter’s star-studded, Oscar-winning The Greatest Show on Earth.

The Hoppy fever eventually broke, but not before making Bill and Grace very wealthy. Childless (Bill’s five marriages produced only one child, a son born to third wife Elinor Fair; tragically, the boy died in his infancy), they retired to California’s Palm Desert in 1953 but remained socially active until the late Sixties, when Bill’s health began to fail. In 1968 he underwent surgery to have a cancerous tumor removed from his lymph gland, and refused to appear in public following that disfiguring procedure. By that time Boyd had contracted Parkinson’s Disease, and he died in 1972 with beloved wife Grace at his side. She enjoyed a healthy and active later life, passing away on September 21, 2010 — her 97th birthday.

I could say a lot more about Bill, Grace, and Hoppy. But this post is already way longer than I intended, so it’ll keep. Meantime, let’s recognize William Boyd’s 117th birthday and the 75th anniversary of his marriage to Grace.

Hoppy birthday, William Boyd: Part 1

One hundred and seventeen years ago today, William Boyd was born in Hendrysburg, Ohio. When he was seven his family moved to Oklahoma, where Bill’s parents both died before he finished high school. Left to fend for himself, the strikingly handsome youth initially found work as a grocery-store clerk, then as a surveyor and oil-field worker. Bill married for the first time in 1917 and soon thereafter moved with his wife to Hollywood, California, where they hoped his pretty face would land him work in moving pictures. Happily for generations of Western fans, they were right.

In 1918 Bill made his screen debut as an unbilled extra in Cecil B. DeMille’s Old Wives for New. The already famous director championed young Boyd and over the next seven years gave him increasingly larger parts. Following Bill’s strong showing as the second male lead in The Road to Yesterday (1925), DeMille made him a full-fledged star in The Volga Boatman (1926) and gave him a pivotal role in the Biblical epic King of Kings (1927).

Boyd’s light, wavy hair and boyish good looks stood him in good stead throughout the silent era. He never reached the heights attained by such matinee idols as John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, or John Barrymore, but he achieved some prominence as a dependable leading man in moderate-budgeted films made by the DeMille-sponsored Producers Distributing Corporation and released by Pathé Exchanges, Inc.

The advent of talking pictures didn’t hurt Boyd’s career; his voice was perfectly suitable to the new medium. When Pathé was absorbed into the conglomerate that became RKO Radio Pictures, Bill maintained his star status for several years, although his films were relatively inexpensive “program pictures”—the type that could play either half of a double bill, according to theater size, location, and clientele. Disaster struck in 1933, when newspapers and wire services across the country ran a photo of him accompanying lurid accounts of a sex-and-booze scandal involving another actor named William Boyd. Although it was a plain case of mistaken identity, the ensuing kerfuffle stopped Bill’s career dead in its tracks. It didn’t help that he was thrice divorced and a big drinker himself. Some media outlets ran corrections, but the damage was already done. RKO dropped Boyd like a hot potato, and for the next two years he could only find work in Poverty Row cheapies that traded on his earlier fame.

In early 1935, independent producer Harry “Pop” Sherman acquired screen rights to the Hopalong Cassidy stories written by Clarence E. Mulford. He raised funds to make a series of six pictures and then cut a distribution deal with Adolph Zukor’s Paramount Pictures. There was one caveat: In the interest of facilitating the series’ marketing and promotion, Paramount insisted that Sherman cast a recognizable star—past or present—in the lead role.

Originally, Pop had planned to make his celluloid Cassidy the grizzled cowpuncher of Mulford’s later novels (which were serialized in the pulp magazine Short Stories prior to book publication by Doubleday), but Paramount’s demand forced him to change direction. Problem was, the major movie cowboys were getting more money than he could afford to pay.

Sherman was turned down by several actors before someone recommended he approach Bill Boyd, who was “at liberty” after having completed four low-budget melodramas for Poverty Row producer George Hirliman. Boyd was not a horse-opera star per se, but two of his most popular starring vehicles—The Last Frontier (1926) and The Painted Desert (1930)—had been epic Westerns.

Although Bill wasn’t especially fond of Westerns, he eagerly accepted Sherman’s offer of five thousand dollars per film with a six-picture guarantee. At the time, neither Boyd nor Sherman had any expectation that the Hopalong Cassidy series would extend beyond the half-dozen entries scheduled for Paramount release during the 1935-36 season. Happily for generations of Western fans, they were wrong.

More on birthday-boy Boyd and Hoppy tomorrow….

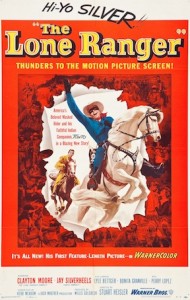

DVR Alert: THE LONE RANGER (1956)

Tomorrow (Saturday, June 2), at 4:30 PM Eastern time, Turner Classic Movies will be running The Lone Ranger (1956), which in my humble opinion is the best celluloid incarnation of this character. A Warner Brothers feature film directed by the underrated Stuart Heisler, this is a happy example of a Western made on an A-movie budget with B-movie pretensions. Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels, TV’s Ranger and Tonto, never looked better. The script recycles many familiar elements of the TV series — i.e., the Lone Ranger masquerades as a crusty old prospector to get information, Tonto goes to town and gets beat up — but sports a relatively mature storyline and even humanizes its chief villain by making him a doting father whose atrocities are committed for the purpose of building an empire he can leave to his only child. The film was clearly designed for family audiences, not just for kids. The narrative is undergirded with a muted plea for racial tolerance that’s just as timely today as it was in 1956. I love this movie — every bit as much now as I did when I first saw it some 50 years ago. It’s a must-have for Lone Ranger fans and well worth recording even if you don’t have the typical baby boomer’s nostalgic fondness for the character. Oh, and did I mention that it has the all-time best “who was that masked man” finale?

Tomorrow (Saturday, June 2), at 4:30 PM Eastern time, Turner Classic Movies will be running The Lone Ranger (1956), which in my humble opinion is the best celluloid incarnation of this character. A Warner Brothers feature film directed by the underrated Stuart Heisler, this is a happy example of a Western made on an A-movie budget with B-movie pretensions. Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels, TV’s Ranger and Tonto, never looked better. The script recycles many familiar elements of the TV series — i.e., the Lone Ranger masquerades as a crusty old prospector to get information, Tonto goes to town and gets beat up — but sports a relatively mature storyline and even humanizes its chief villain by making him a doting father whose atrocities are committed for the purpose of building an empire he can leave to his only child. The film was clearly designed for family audiences, not just for kids. The narrative is undergirded with a muted plea for racial tolerance that’s just as timely today as it was in 1956. I love this movie — every bit as much now as I did when I first saw it some 50 years ago. It’s a must-have for Lone Ranger fans and well worth recording even if you don’t have the typical baby boomer’s nostalgic fondness for the character. Oh, and did I mention that it has the all-time best “who was that masked man” finale?

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net