EDitorial Comments

“What, another one?” Yep….

Just an hour ago I okayed a digital proof of Murania’s latest book — yes, later than Western Movie Roundup — and ordered bound copies. This is another quickie I whipped up after deciding to attend next week’s Western Film Fair in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. It should do pretty well down there, I think.

Cliffhanger Classics collects all 20 essays on serials printed in Blood ‘n’ Thunder since the first issue came out ten years ago. It’s quite a coincidence that the number is a nice round 20. It’s even more of a coincidence that the coverage is evenly divided between silent and sound serials. BnT readers know that motion-picture chapter plays are very close to my heart: As I explain in a newly written Introduction, I’ve studied and collected them for many years. So BnT doesn’t print gushy fanboy puff-pieces that rehash the same tired facts and suppositions about serials; our essays on episodic thrillers are backed by solid research and, in many cases, interviews with the actors, writers and directors involved.

Those who’ve been waiting patiently for Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders, my comprehensive history of silent-era serials, can be forgiven for being annoyed if they think I’ve postponed that book yet again. But it’s not so. DD&MM is in the home stretch, and throwing together Cliffhanger Classics didn’t change our timetable for that book’s completion.

When I use the term “whipped up” to describe preparation of the new tome, I’m really talking about the yeoman work done by Murania Press art director Chris Kalb. My part of the task was fairly simple: collating the articles, doing minor re-edits, making a few corrections, and writing an intro. Using his Best of Blood ‘n’ Thunder design as a template, Chris did the interior layout in record time. And then, to my amazement, he assembled a dynamic, colorful collage from bits and pieces of a dozen serial posters I’d sent him for possible use on the cover.

When I use the term “whipped up” to describe preparation of the new tome, I’m really talking about the yeoman work done by Murania Press art director Chris Kalb. My part of the task was fairly simple: collating the articles, doing minor re-edits, making a few corrections, and writing an intro. Using his Best of Blood ‘n’ Thunder design as a template, Chris did the interior layout in record time. And then, to my amazement, he assembled a dynamic, colorful collage from bits and pieces of a dozen serial posters I’d sent him for possible use on the cover.

Naturally, the contents of this book will be familiar to those of you who’ve been long-time Blood ‘n’ Thunder subscribers. But my target market for this particular book is the film-buff crowd, members of whom attend such conventions as the Western Film Fair just as regularly as we pulp-fiction devotees attend PulpFest and the Windy City Pulp and Paper show. Naturally, they will not have seen or read this material before. I expect them to take to this book like the proverbial duck to water. Of course, if you’d like to have a nice, spiffy new volume collecting all of BnT‘s serial essays between two covers, I won’t try to talk you out of buying Cliffhanger Classics.

For the record, the book is 308 pages and nearly a hundred thousand words long. There are two picture galleries of 20 pages each; they reprint rare stills, posters and lobby cards, including some that did not accompany the essays as initially published in BnT. Believe me, Cliffhanger Classics makes a dandy companion volume to The Best of Blood ‘n’ Thunder, especially since it has the same dimensions (six by nine inches) and the same spine design.

It’s a nifty little book, if I do say so myself. You can order it from the Home page, where it’s listed under “Latest Releases.”

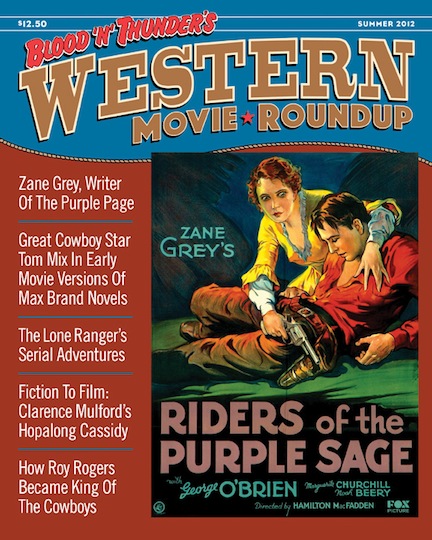

A New Magazine from Murania Press!

Surprise, surprise.

For some time now I’ve contemplated launching a separate magazine to cover Western movies. I’ve been seriously researching film history for nearly four decades and have devoted more time and effort to the Western than any other genre. (The serial isn’t a genre, it’s a format.) Over the years I’ve amassed gobs of information about horse operas and interviewed dozens of people who helped make them from both sides of the camera. At one time I had a collection of several thousand vintage photographs from Westerns, and though I’ve since sold the whole kit and kaboodle, before doing so I scanned hundreds of stills for possible publication and can access the others at my convenience.

Having written one book on Westerns (Filming the West of Zane Grey) and co-edited another (Don Miller’s Hollywood Corral: A Comprehensive B-Western Roundup), I’ve often been asked to lend my expertise, such as it is, to projects covering similar ground. Since 2004, for example, I’ve been editing Lone Pine in the Movies, a magazine published for, and distributed during, the annual Lone Pine Film Festival, which celebrates motion pictures — most of them Westerns — produced in and around that small California community. As a result my “field research” remains ongoing.

The recent all-Westerns double issue of Blood ‘n’ Thunder gave me an excuse to include a considerable amount of movie-related material, and it’s actually the foundation on which the first issue of Murania’s new magazine has been built. To be honest, the issuance at this time of Blood ‘n’ Thunder’s Western Movie Roundup has been occasioned by my spur-of-the-moment decision to attend the upcoming Western Film Fair in Winston Salem, North Carolina. It’s the group’s 35th annual convention and will be the first I’ve been to in more than two decades. Originally based in Charlotte, the Western Film Fair previously was a must-attend event for me. In the early years its guest stars included many B-Western stars, including Charles Starrett, Lash LaRue, Sunset Carson, Eddie Dean,and Bob Allen, to name a few off the top of my head. Such perennial horse-opera heavies as Terry Frost and Pierce Lyden were among the regulars, as were former B-Western ingenues Jennifer Holt, Lois January, Peggy Stewart, and Dorothy Gulliver.

As the Thirties and Forties stars began dying off, I gradually lost interest in the Charlotte show. Upon moving to Los Angeles in 1992, I gave up on the Film Fair for geographical reasons but followed its progress via reports in movie-hobbyist publications like Classic Images and The Big Reel. The guest lists were increasingly comprised of actors from more recent Western feature films and TV shows. Fascinating people, but none I had much interest in.

Over the past several years some old friends in the hobby have been encouraging me to return to the fold, as it were. And even though my plate is full to overflowing at the moment, I actually have a compelling reason to go south this summer, if only briefly. So, with the knowledge that I could kill two birds with one stone, I agreed to attend the 2012 Western Film Fair. But I didn’t see any point in showing up empty-handed.

At my urging, BnT art director Chris Kalb quickly assembled this new magazine. I didn’t have time to write anything for it, other than an introductory editorial, so the first issue consists entirely of articles “repurposed” from recent issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder. I say this up front because I’m not trying to pull a fast one on BnT subscribers and regular readers who might be tempted to buy it. The new magazine will be targeted to Western-film aficionados who, for the most part, have never seen BnT. Subsequent issues will, of course, contain newly written material. I still have in my files many hours of interviews that can be transcribed and lots of original research to mine for articles. In every way Western Movie Roundup will maintain the level of quality readers have come to expect from Blood ‘n’ Thunder.

Watch this space for information on ordering and/or subscribing. The inaugural issue has just gone to the printer and the Western Film Fair begins a week from Thursday. Once I get past that, I’ll update the site with a page devoted to WMR, as Chris and I call it.

The Book Cave: Enter At Your Own Risk

Recently I was interviewed by Ric Croxton and Art Sippo, co-hosts of the popular Book Cave podcast, which caters to fans of genre fiction, comic books, and other pop-culture storytelling forms. Every year around this time they graciously allow me to plug PulpFest as well as upcoming issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder and other Murania Press books. Our conversation has just been posted, and while I can’t honestly say I was at the top of my game during the recording session (which was interrupted when my elderly neighbor needed emergency aid) I think it covers all the bases.

Pulp Historian Albert Tonik’s Collection Will Be Auctioned at PulpFest

Albert Tonik, long-time fan, scholar and collector of pulp magazines and related popular-culture artifacts, has decided to sell his holdings and has chosen PulpFest as the most appropriate venue to do so. Therefore, the vast majority of lots offered at this year’s Saturday-night auction will be choice items from Al’s huge collection of hardcovers, paperbacks, pulps, fanzines, dime novels, comic books, and especially reference books that are both scarce and desirable.

Albert Tonik, long-time fan, scholar and collector of pulp magazines and related popular-culture artifacts, has decided to sell his holdings and has chosen PulpFest as the most appropriate venue to do so. Therefore, the vast majority of lots offered at this year’s Saturday-night auction will be choice items from Al’s huge collection of hardcovers, paperbacks, pulps, fanzines, dime novels, comic books, and especially reference books that are both scarce and desirable.

One of the last surviving PulpFest attendees who actually bought pulps off the newsstands, Al discovered fandom several decades ago and began collecting anew the rough-paper magazines he enjoyed so much as a youth. But his activity didn’t stop there: Al was determined to document the lives and careers of pulp writers, artists, editors, and publishers. He assiduously tracked down and made contact with surviving pulp-industry veterans, corresponding with many and meeting some face to face. More than a few considered him a friend and granted him unlimited access to their files for his research.

Over a period of several decades, Al researched aspects of pulp history previously covered sketchily, if at all. He unearthed long-buried records — letters, ledgers, invoices, inter-office memos — that enabled him to identify the works of pulp writers who had worked under pseudonyms, to determine how much they had been paid for their labors, where and when their stories had been reprinted (if at all), and so on. In the course of this research, which he came to enjoy as much if not more than reading the actual pulps themselves, Al amassed a huge library of reference works that facilitated cross-referencing and added to the wealth of knowledge he uncovered through his friendships with veteran pulpsters.

Al has loved sharing his knowledge. As an early member of PEAPS (the Pulp Era Amateur Press Society), he became well known for his contributions entitled “Ramblings of a Perambulating Pulp Fan.” He transcribed interviews, compiled exhaustive bibliographies, and wrote fact-filled articles for such popular fanzines as Echoes, Pulp Vault, The Pulp Collector, Purple Prose, and my own Blood ‘n’ Thunder. Al never wrote a pulp-history book himself, but he supplied hard-to-find information to more than a dozen tomes penned by his friends and fellow pulp scholars.

Although Al remains in relatively good physical condition for his 87 years of age, he has decided it’s time to dispose of the collection he spent so long compiling. He wants this treasure trove of material to be disseminated among his fellow hobbyists and to that end has asked PulpFest to auction the material.

Among the many treasures that will be offered during our August 11th auction will be Leonard A. Robbins’ multi-volume The Pulp Magazine Index, Marshall B. Tymn’s and Mike Ashley’s Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, Sam Moskowitz’s Under the Moons of Mars (signed by the author), Michael L. Cook’s Mystery, Detective, and Espionage Magazines, Quentin Reynolds’ The Fiction Factory, a complete run of the quarterly PEAPS mailings, a bound volume of Lynn Hickman’s The Pulp Era, runs of Echoes, The Pulp Collector, Pulp Vault, Rocket’s Blast Comic Collector, and other fanzines, a few issues of Standard’s Thrilling Comics and Street & Smith’s Shadow Comics, several issues of Jungle Stories and various Western pulps, many issues of The Pulp Review/High Adventure, a large number of Jim Hanos’ pulp reprints, film and television scripts, superhero paperbacks, and much more.

Over the years Al has been one of the hobby’s most generous participants. He has given us a great deal — including his friendship — and we’re pleased to have a role in giving something back, in addition to finding good homes for the books and magazines he has treasured for so many years.

More information will be supplied after the PulpFest staff has been able to catalog Al’s voluminous holdings. This auction is yet another reason to be excited about PulpFest 2012, which is almost certain to be the best yet!

More on “10-20-30” Melodrama

In addition to providing visceral thrills, 10-20-30 “mellers” regularly trafficked in narrative devices that would later be incorporated into motion-picture serials. They often revolved around a struggle for vitally important papers: the map to hidden wealth, the deed to a home, the will to an estate, the plans to an invention, the confession to a crime, the bill-of-sale for disputed property, or the birth certificate establishing parentage of a character whose fate was tied to his or her ancestry. In a chapter play, any document of that type might serve as what Pearl White termed “the weenie” and what Alfred Hitchcock later called “the MacGuffin.”

Another plot catalyst carried over from stage to film was the sudden death, disgrace or disappearance of a father, which forced his dutiful daughter to undertake arduous or unpleasant tasks. Like their 10-20-30 counterparts, the heroines of motion-picture serials always rose to the challenges presented them, invariably completing their missions, defeating their opponents, and triumphing over adversity.

Today, many people associate the word “melodrama” with post-World War II stories of domestic travail involving repressed or unfulfilled housewives. But during the 10-20-30 era it was used to describe overwrought plots and exaggerated situations. Suspense and sensation were the currency of these blood-and-thunder epics, which consciously downplayed emotional nuance in favor of externalized action. Reducing the dramatis personae to stereotypes was essential to maintaining narrative speed and clarity. Character delineation was always sublimated to physical action.

Like the silent serials, 10-20-30 mellers were ground out like sausages and seldom strayed from the well-established recipe. To practitioners of the form, ingenuity was defined as a writer’s ability to mix standard ingredients skillfully enough to create the illusion that spectators were being served something new. In another parallel to chapter plays (especially those of the Twenties), 10-20-30 melodramas were produced on fairly rigid budgets. Experienced theater owners knew almost to the seat how many local patrons could be coaxed to attend each new production, so any half-decent play that stuck to its budget was assured of turning a profit.

Ten-twenty-thirty melodrama offered carefully measured rations of comedy and pathos but emphasized nail-biting suspense and surprisingly vigorous, elaborately staged action. Iconic images associated with early serials — the heroine tied to railroad tracks, bound to a log sliding toward a buzz saw, or dangling from frayed ropes above deep pits and deathtraps — actually derive from scenes in famous 10-20-30 productions. The stagecraft behind these shows was remarkably sophisticated for its time, especially once electrical devices made certain illusions easier to create.

The sensational stage melodrama perished for one simple reason: money. During the 20th century’s early years, 10-20-30 admission prices gradually crept up to 25-50-75, keeping pace with rising production costs. But nickelodeons and other venues featuring motion pictures were charging five to ten cents for several reels of entertainment. Since melodrama was a staple of early motion pictures, it was inevitable that thrill-hungry, working-class patrons would forsake the more expensive vehicle for the cheaper one. Moreover, it was a logical choice. Narrative silent film, dominated in the waning years of 10-20-30 by one-reelers, was the perfect medium for stories built around easily identifiable character types and visual thrills. Realism was an additional inducement: movie horses did not run on treadmills and fire scenes could be staged without resorting to camouflaged smoke pots.

Popular-priced stage melodrama had already passed from the American pop-culture scene by 1914, when Pearl White’s Pauline faced her first perils. It disappeared from the pop-culture landscape with amazing rapidity — almost overnight, in fact. But filmmakers made celluloid adaptations of 10-20-30 warhorses throughout the silent years and even into the early talkie period.

The Movie Serial’s Precursor: “10-20-30” Stage Melodrama

(Have you ever wondered from whence the motion-picture serial developed? Here’s an excerpt from my upcoming book, Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders, which explains the chapter play’s origin at some length.)

From its beginnings, the motion-picture serial reflected the influences of popular-priced stage melodrama and mass-market fiction, the latter delivered to thrill-hungry readers in cheaply produced woodpulp magazines. Chapter-play writers hewed closely to the well-established conventions of pulp periodicals and sensation-based theatrical productions because they hoped to attract the same consumers to which those mediums appealed: largely working-class folks, and a small but significant percentage of the middle class. The relatively short lengths and primitive storytelling techniques of nickelodeon-era motion pictures made inevitable a reliance on melodrama, with its simple narratives, broadly sketched situations, and clearly defined character types.

Stage melodrama emerged at the turn of the 19th century, but it took nearly a hundred years to evolve into the form from which early filmmakers drew plots, themes, and concepts. By then known as “10-20-30” (reflecting the prices asked by theaters specializing in this sort of fare), the thrill-charged stage melodrama flourished in small towns and big cities alike, playing mostly to uncritical, unsophisticated, and sometimes marginally literate spectators. Many successful shows of the type premiered in New York City, where they were known generically as “Third Avenue melodrama,” owing to the proliferation of 10-20-30 theaters along that particular thoroughfare.

The hallmark of 10-20-30 was sensationalism. Nineteenth-century melodrama is often identified with mustache-twirling, black-garbed villains of the “Curses, foiled again” stripe, badgering defenseless young women for overdue rent money, but 10-20-30 productions went far beyond eyeball-rolling malefactors and sobbing ingenues.

The average 10-20-30 story was presented in four acts and incorporated as many as 20 separate scenes, some lowering the curtain in the immediate aftermath of thrilling situations — not unlike the serial’s “cliffhanger” endings — calling for elaborate scenic effects. The climax of Joseph Arthur’s The Still Alarm (1890, and adapted to celluloid several times during the silent-movie era) boasted a race to the rescue in which real horses, hitched to a real fire engine, galloped on a treadmill (backed by a revolving cyclorama to create the illusion of speed) to the scene of a conflagration represented by smoke wafting across the stage from carefully hidden pots.

The heroine of Charles T. Dazey’s In Old Kentucky (1893), which also had several screen incarnations, was called upon to swing by rope across a deep chasm and rescue a racehorse from a burning stable. Ramsey Morris’s The Ninety and Nine (1902) depicted the passing of a locomotive through a forest fire, and Charles A. Tyler’s Through Fire and Water (1903) simulated the plunging of a canoe over a waterfall. Such effects required complicated sets and apparatus, and were occasionally achieved with astonishing verisimilitude. Both natural and unnatural disasters paraded nightly across the stages of 10-20-30 theaters.

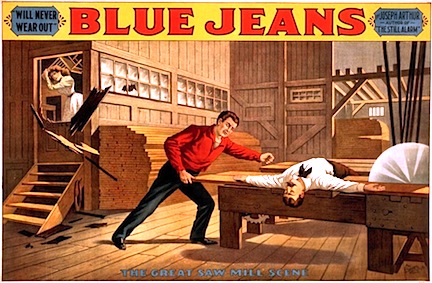

Perhaps the ne plus ultra of such thrills was the climactic sequence of Joseph Arthur’s Blue Jeans (1890), arguably the most influential 10-20-30 melodrama. Villainous Ben Boone (played by George Fawcett) lures hero Perry Bascom (Robert Hilliard) and wife June (Jennie Yeamans) to a lumber mill. The young woman is locked in a small office adjoining the plant, where her husband is knocked unconscious and placed on a conveyor belt atop a log being carried toward a whirling buzz saw. There was nothing phony about this scene — which worked on two levels, as explained by the Boston Evening Transcript’s Jeanette Leonard Gilder, writing as “Brunswick”:

The fourth and last act shows us the Buzz Saw going at full speed. To show that the saw is as real as the buzz, it is made to cut thick boards into lengths, and cold shivers pass over the audience as it settles itself down to enjoy what it thinks, I will not say hopes, may be a real tragedy. . . . With a fiendish smile upon his face, [villain Ben Boone] points to the buzz-saw, winks at the audience and places the unresisting form of Hilliard within a few feet of the cruel wheel. He is being drawn nearer and nearer his doom, and we expect every moment to see the buzz-saw do to the prostrate actor what King Solomon intended to do to the disputed baby, when [the heroine] June breaks through the door and grabs him away from certain death just before he is split in twain.

Not surprisingly, Blue Jeans was a huge hit — the gaslight-era equivalent of today’s “water cooler” TV programs. Fortunately, actor Hilliard escaped injury night after night, but the potential for disaster was there in every performance. (The buzz-saw bit became so firmly ingrained in memory that early serial writers and directors referred to any hazard-portraying chapter ending as “a Blue Jeans finish.”) Acting in 10-20-30 melodramas was not for the faint-hearted or weak-limbed: cast members were expected to do stunts such as wire-walking and rope-swinging in addition to trading poorly-pulled punches and making the occasional leap from a wood-flat scaffold painted to resemble a cliff.

(Part Two of this excerpt follows tomorrow. How could I cover this topic without giving you a “To Be Continued”?)

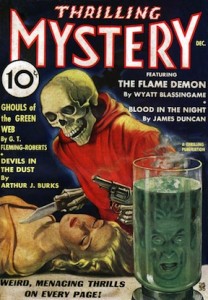

The Unbearable Lightness of Leo

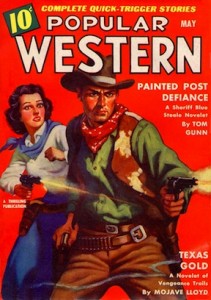

Lately I’ve been revisiting the “Thrilling Group” pulp magazines published by Ned Pines, whose numerous companies included Standard Magazines, Beacon Magazines, Better Publications, and Nedor Publishing Company. Pines, as many of you know, had a fetishistic attachment to the word “Thrilling,” which he used in no less than a dozen magazine titles. (He also had a thing for “Popular” and “Exciting,” which he employed with equal promiscuity.) He published 75 rough-paper magazines between 1931 and 1958, always maintaining healthy market share and outlasting all but one of his major competitors. For most of its existence the Thrilling Group was guided by editorial director Leo Margulies, who enjoyed the respect and admiration of writers and other editors alike.

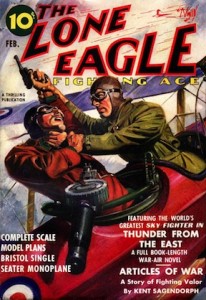

During the Thirties, Pines’s flagship titles included Thrilling Adventures, Thrilling Detective, Thrilling Love, Thrilling Mystery, Thrilling Ranch Stories, Thrilling Sports, Thrilling Western, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. In 1933 he entered the burgeoning single-character field with The Phantom Detective and The Lone Eagle. Pines was not an innovator. He never aspired to lead; he was content to follow. Other publishers took the risks while he sat back to see how they would fare. Street & Smith, having published the first single-genre magazines (Detective Story, Western Story, Love Story, Sport Story), began the hero-pulp revolution with The Shadow. Hugo Gernsback turned science fiction into a viable category with Amazing Stories. In retooling Dime Mystery, Popular Publications created the “weird menace” subgenre. Ned Pines and Leo Margulies tracked the progress of these successful pulps before launching competing titles. In every case they waited for proof that the new trends were sustainable.

During the Thirties, Pines’s flagship titles included Thrilling Adventures, Thrilling Detective, Thrilling Love, Thrilling Mystery, Thrilling Ranch Stories, Thrilling Sports, Thrilling Western, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. In 1933 he entered the burgeoning single-character field with The Phantom Detective and The Lone Eagle. Pines was not an innovator. He never aspired to lead; he was content to follow. Other publishers took the risks while he sat back to see how they would fare. Street & Smith, having published the first single-genre magazines (Detective Story, Western Story, Love Story, Sport Story), began the hero-pulp revolution with The Shadow. Hugo Gernsback turned science fiction into a viable category with Amazing Stories. In retooling Dime Mystery, Popular Publications created the “weird menace” subgenre. Ned Pines and Leo Margulies tracked the progress of these successful pulps before launching competing titles. In every case they waited for proof that the new trends were sustainable.

Not only was Margulies averse to risk, he strenuously opposed the imposition of any personal editorial point of view. The Thrilling pulps had individual editors, at least in a titular sense, but for the most part they were literally edited by committee. Three sub-editors reviewed every story that was tentatively selected for publication. A unanimous vote of approval was necessary to get every yarn published. In disputed cases Leo himself was the final arbiter.

There were exceptions to this process. Margulies reportedly gave Mort Weisinger considerable latitude in the editing of Thrilling Wonder Stories because neither he nor most sub-editors were conversant with the very specific traditions and characteristics of science fiction. The novel-length adventures of the Phantom Detective didn’t see print unless they passed muster with Marcus Goldsmith, an elderly Thrilling Group investor who rather inexplicably maintained a proprietary interest in that particular series. But for the most part, Leo ran things his way.

Of course, you can’t argue with success, and some might think it churlish of me to try. But I’ve never warmed up to the Pines pulps — and not for lack of trying, believe me.

It’s not that Thrilling Group pulps are bad. On the contrary, they were obviously produced with competence if not inspiration. They feature work by solid, professional fictioneers — not the first-tier writers, certainly, but many of the reliable second-tier scribes. And they are nothing if not uniform, a quality that normally is very much to be desired.

But, see, there’s the rub. When uniformity doesn’t rely on excellence, the result is often blandness. And I find the Thrilling pulps bland. They’re assembly-line products that sometimes exhibit ingenuity but never brilliance. They are, in the main, very much like the oeuvre of Norman A. Daniels, one of Margulies’ most prolific contributors. Daniels was nothing if not reliable; he was proficient in multiple genres and could be consistently counted upon to supply readable, entertaining fiction. But I think it’s fair to say that, just as he never wrote a really bad story, he never wrote a really good story. Despite the millions of words he turned out (sometimes in collaboration with his wife), Daniels never penned a truly memorable yarn — which is to say, one that had a life beyond the pulps and latter-day fan-published reprints. You never find him represented in mass-market anthologies of rough-paper stories. His Thrilling Group series characters are cut to familiar patterns and based on those created by better writers for more daring and innovative publishers. In short, he specialized — quite deliberately, I think — in middle-of-the-road pulp fiction.

The entire Thrilling line is middle-of-the-road in concept and execution, with the exceptions of the post-WWII Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories — which, under the editorial guidance of Sam Mines and Sam Merwin, finally jettisoned the juvenile approach initially taken by Mort Weisinger and Oscar Friend. Both magazines published some truly classic science-fiction stories in the late Forties and Fifties, and I find them to be the liveliest little fillies in the entire Thrilling stable. It’s significant that they were practically the only ones which didn’t have Leo’s bit in their mouths.

DC Comics editor Jack Schiff, who worked for Pines and Margulies during the Thirties before leaving pulps for funny books, told a Pulpcon audience that Leo saw his magazines as appealing primarily to adolescents. That might account for their blandness. Thrilling Detective and its fellow Pines-published crime mags were the least hard-boiled detective pulps in the business with the exception of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. At a time when most weird-menace pulps were ratcheting up their levels of sex and sadism, Thrilling Mystery remained positively demure by comparison. The apocalyptic, emotion-drenched, no-holds-barred action of Popular Publications’ The Spider and Operator #5 was nowhere to be found in the pleasant but predictable adventures of the Phantom, the Black Bat, the Masked Detective, or any other Thrilling Group heroes. They were light, airy, fluffy, compared to the sterner stuff dished up by Norvell Page, Frederick C. Davis, and Wayne Rogers.

DC Comics editor Jack Schiff, who worked for Pines and Margulies during the Thirties before leaving pulps for funny books, told a Pulpcon audience that Leo saw his magazines as appealing primarily to adolescents. That might account for their blandness. Thrilling Detective and its fellow Pines-published crime mags were the least hard-boiled detective pulps in the business with the exception of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. At a time when most weird-menace pulps were ratcheting up their levels of sex and sadism, Thrilling Mystery remained positively demure by comparison. The apocalyptic, emotion-drenched, no-holds-barred action of Popular Publications’ The Spider and Operator #5 was nowhere to be found in the pleasant but predictable adventures of the Phantom, the Black Bat, the Masked Detective, or any other Thrilling Group heroes. They were light, airy, fluffy, compared to the sterner stuff dished up by Norvell Page, Frederick C. Davis, and Wayne Rogers.

I know there still exists among present-day pulp fans a sizable constituency in favor of the Thrilling Group. Let’s hear from some of you. Am I being too hard on Leo and his boys? Opinions, please.

Chandu? Can Do!

I don’t remember exactly how, when or where I first learned about Chandu the Magician. Most likely I saw stills from it in Famous Monsters of Filmland, Castle of Frankenstein, or one of the other “monster mags” published during the Sixties. I do remember being intrigued by the character right away, and a little research told me he was created for a radio show that was wildly popular in the early Thirties. It didn’t occur to me — at least, not back then — that some of his airwave adventures might have survived in the form of transcription discs prepared when the series was syndicated.

I was especially fascinated to learn that Bela Lugosi appeared in the two Chandu films produced after the radio broadcast became a hit. The first, Chandu the Magician (1932), cast him as the series’ arch-villain, typically referred to as “the malevolent Roxor.” But the second, a 12-chapter serial fittingly titled The Return of Chandu (1934), gave him a shot at the title role. This really piqued my curiosity; just what sort of hero was this Chandu that he could be portrayed by Bela Lugosi?

Several years passed before I was able to screen feature or serial. In the interim I learned that Chandu’s real name was Frank Chandler; that he had gone to India after the first World War; that he spent years there studying occult practices common in the East; that he was given the name “Chandu” by a yogi whom he periodically consulted; that he loved the beautiful Nadji, last in a long line of Egyptian princesses; and that he belonged to a secret society committed to opposing evil men who employed the black arts in their pursuit of wealth and power.

In 1972 I saw Chandu the Magician at a New York City museum screening. Some audience members thought it too campy, but I loved every ultra-melodramatic minute. A few years later I caught up with Return of Chandu, not as good but certainly interesting in its own right. By this time — long before home video — I was collecting 16mm prints of vintage movies and in fairly short order tracked down two feature films edited from the serial, Return of Chandu and Chandu on the Magic Island.

Finally, in the late Seventies, I discovered that Chandu enjoyed two radio incarnations: The first run ended in 1934 or thereabouts, but there had been a 1949 revival using lightly updated rewrites of the original scripts. Few of the Thirties broadcasts (featuring Gayne Whitman as Chandu) seemed to survive, but all the revival episodes (starring Tom Collins) existed and tape copies of them could be purchased from various Old-Time Radio hobbyists. It took me a while, but eventually I acquired the entire run.

Still later, after discovering the works of pulp writer Talbot Mundy, I came across one of his novels that could well have served as a blueprint for the Chandu series. The similarities were numerous and profound. I remember thinking, “One of these days, I ought to write an article comparing the two.” Well, it took me more than a decade to turn that thought into action, but I’ve finally completed a history of Chandu. It’ll appear in the upcoming Tenth Anniversary Special issue of Blood ‘n’ Thunder.

I think you’ll find this piece very interesting, as it lays out a case that one of Mundy’s most popular yarns — one of his best-selling books — was ruthlessly pillaged for the characters and elements that made Chandu the Magician such a sensation in the early Depression years. The article is illustrated with many rare stills, including behind-the-scenes photos taken during production of the 1932 feature film and staged shots of Gayne Whitman in character, enacting scenes from the earliest radio episodes. If you don’t know anything about Chandu — or even if you do — you’re in for a treat.

Promising Pulp-Mag Series Characters Who Never Really Caught Fire

One of the items for sale on our Collectibles page is the November 23, 1935 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly. The cover story is Erle Stanley Gardner’s “The Silver Mask Murders,” featuring his short-lived vigilante hero The Man in the Silver Mask. This was the last of three novelettes Gardner wrote about this Shadow/Spider/Phantom Detective simulacrum. Readers following the series had to have been disappointed that it ended with several loose ends dangling. Other entries were obviously planned; “Murders” ends with its criminal mastermind plotting revenge after narrowly evading a trap set by the Silver Mask.

I assume the basic concept must have been palatable to DFW customers, especially the younger, action-hungry readers. The Silver Mask was another well-meaning playboy with seemingly unlimited resources at his disposal. He had a pretty assistant and a mute Chinese servant well schooled in the art of Oriental torture. His lavish hideout — outfitted with cutting-edge gadgets and boasting a perfectly swell dungeon — was constructed beneath the streets of Chinatown, accessible only to a chosen few familiar with the network of secret panels, trap doors, and sewer tunnels leading to it.

The Silver Mask didn’t actually engage in torture; usually the threat of physical violence was enough to loosen the tongues of hapless henchmen he captured, blindfolded, and took to his underground lair. But at least once in every story he was asked if he would torture captives if absolutely necessary to elicit vital information — and he always refused to rule it out.

The Silver Mask didn’t actually engage in torture; usually the threat of physical violence was enough to loosen the tongues of hapless henchmen he captured, blindfolded, and took to his underground lair. But at least once in every story he was asked if he would torture captives if absolutely necessary to elicit vital information — and he always refused to rule it out.

The Man in the Silver Mask series, while reasonably entertaining, didn’t come remotely close to being Gardner’s best work during that prolific period. I don’t think it’s a stretch to assume that he was assigned to develop such a character, dutifully agreeing even though his heart wasn’t in it. The series fairly teems with missed opportunities. The Silver Mask himself remains off stage for long intervals. Thornton Acker, the brilliant attorney and “fixer” who emerges as the series’ main villain, dominates “The Silver Mask Murders” by devising an apparently foolproof scheme to discredit the masked vigilante. Gardner in this story seems primarily interested in establishing Acker as a formidable foe; the Mask derails the malefactor’s plans but benefits most from the unexpected (and convenient) meltdown of a secondary villain who believes he’s been framed by the crooked fixer.

The adventures of The Man in the Silver Mask remind me of another brief series that held promise which went unrealized: H. Bedford-Jones’ “The Ghost of Screwface Hanlon” appeared in three consecutive 1931 issues of Short Stories before ending on the verge of bigger and better things. The protagonist was a reformed minor criminal who, for dubious reasons, impersonated a master miscreant long believed dead. The “revived” Screwface Hanlon was poised to wreak havoc on the underworld when Short Stories abruptly terminated the series. Like Gardner with the Silver Mask tales, Bedford-Jones seemed to be slumming; he introduced several fascinating ideas but failed to provide a substantive payoff to any of them. The third and final yarn at least offered a clear-cut resolution to the story arc, but it was anticlimactic and unsatisfying.

Among the “hero pulps” were several short-lived titles whose eponymous adventurers didn’t catch the fancies of readers: Captain Hazzard, Captain Zero, Captain Satan (hmmm…a pattern emerges), and the Secret Six, to name a few. But there must have been dozens of series in other pulps that began promisingly only to fade into obscurity after a handful of entries. If you can think of others, send them along in a comment to this post. Who knows, there might be an interesting Blood ‘n’ Thunder article in this topic.

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net