EDitorial Comments

CLASSIC PULP REPRINTS 2015 Slate

Although it’s been a long time between issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder and volumes in our Classic Pulp Reprints series, that doesn’t mean we haven’t been planning and working on Murania’s 2015 slate of releases. The planned double issue of BnT has ballooned into another triple issue (but without a book-length novel this time) that will debut at next month’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention. I’ll have more to say about the issue in a future post. Today let’s concentrate on the upcoming Classic Pulp Reprints releases.

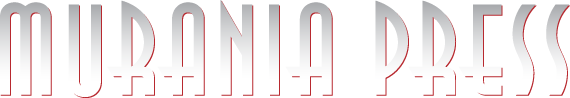

First up will be J. Allan Dunn’s The Island, his 1922 sequel to Barehanded Castaways, which was the second book in our reprint line. Island, like Castaways before it, originally appeared in Adventure magazine and—quite inexplicably—never saw publication between hard covers in America. It continued the saga of men with widely differing backgrounds coming together to survive on a small Pacific island after being shipwrecked. Barehanded Castaways ended with a handful of survivors attempting a return to civilization on a sturdy sea-raft while several of their comrades stayed behind. The Island picks up where the earlier tale left off and is every bit as engrossing as its predecessor. The Murania Press edition has a similar design to our Castaways, even to using the same N. C. Wyeth painting for the cover, so that buyers can instantly see that it’s a companion volume to the first story. Look for it next month.

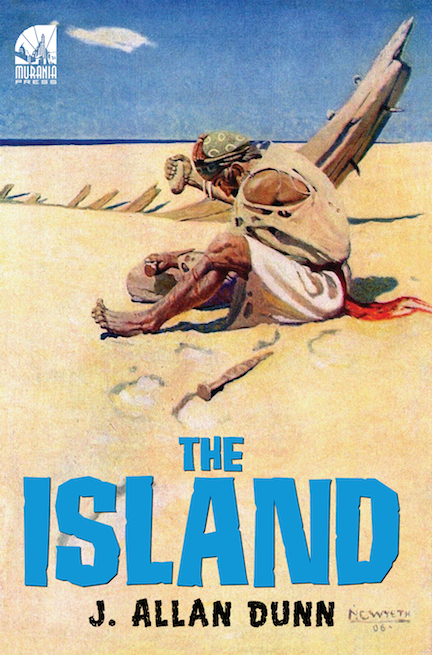

Next in the series is what I believe to be one of the unsung great pulp yarns of the early Thirties, originally published in a 1933 issue of the Popular Publications magazine Dime Mystery Book. Written by William Corcoran and titled The Purple Eye, it’s a 60,000-word novel that could very well have been the template for later hero pulps from Harry Steeger’s Popular. Corcoran is largely forgotten today, but he was a successful fictioneer who wrote for most of the major detective pulps (Black Mask, Detective Story, and Detective Fiction Weekly among them), the top anthology pulps (including Argosy, Short Stories, and Adventure, which he briefly edited), and some of the best slicks (Liberty, Cosmopolitan, and The American Magazine).

The Purple Eye has as its protagonist one of those globe-trotting millionaire adventurers so common in the hero pulps. Wayne Saxon returns to New York City from a round-the-world trip to find his home town terrorized by a crime cult, The Brotherhood of Baktuun, headed by the brilliant but seldom-seen Purple Eye. The police prove unable to halt the Brotherhood’s depredations, and Saxon combats the Eye’s murderous followers with the aid of a vigilante band known as The Secret Hundred. The Purple Eye moves like a runaway train and crackles with action, and after reading it you’ll wonder why this glittering little gem isn’t better known by pulp aficionados.

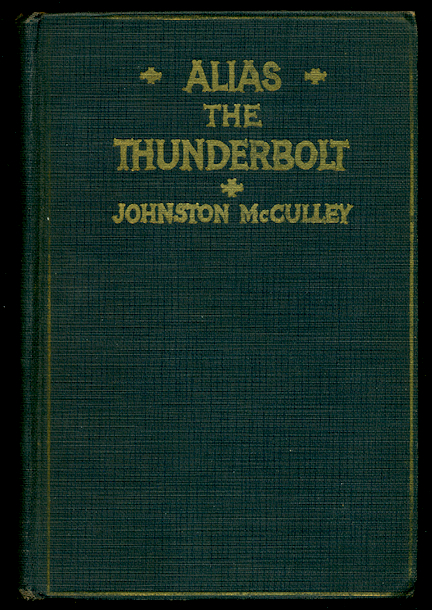

Coming later this year is our Johnston McCulley Collection, three volumes of crime and mystery yarns written by the creator of Zorro and originally published in Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. I’ve chosen novel-length compilations of novelettes featuring favorite McCulley series characters. These books are Alias The Thunderbolt, The Return of Black Star, and The Spider Spins His Web. Each volume will include a specially commissioned essay on the prolific author. Thunderbolt and Spider reprint the first three installments of their respective series, while Black Star contains novelettes from that series’ third year. I’ll share more information on this trio as their publication draws closer.

Finally, this year will see publication of the first “double” volume in the Classic Pulp Reprints line. Two by Sheehan (that’s just a tentative title; I hope to come up with something snappier) will offer a brace of exemplary short novels written by Perley Poore Sheehan for the Munsey pulps: 1913’s The Copper Princess and 1915’s The Abyss of Wonders. Neither story is easy to categorize, but together they offer enough fantasy, mystery, melodrama, science fiction, and lost-race adventure to satisfy any fan of pulp fiction. Unlike many pulpateers of the Teens, Sheehan wrote in a fresh, vibrant style that makes his novels eminently readable a hundred years after they first saw print. Two by Sheehan will also include a long essay covering not only Sheehan’s pulp career but also his long involvement with Hollywood. The books in our Classic Pulp Reprints line generally sell for $19.95 each, but this one will carry a retail price of $24.95.

We’ve bitten off a lot to chew on for 2015 but, like I said earlier, work on these books is already well underway. Keep checking back here for further information and release dates.

Birthday Boy: George F. Worts

A popular and prolific purveyor of pulp fiction, George Frank Worts was born in Toledo, Ohio, on this day in 1892. There was little about his upbringing to suggest that he would eventually become a ubiquitous presence in such notable rough-paper magazines as Argosy, Blue Book, and Short Stories. The most adventurous thing he had ever done was “punch brass”—operate a wireless radio set—aboard ships that sailed up and down the Central American coast.

During one fateful voyage Worts made the acquaintance of a writer who, as he later said, “painted the joys of free-lancing so vividly that I could not resist the call.” Soon thereafter he abandoned seafaring life to attend Columbia University. He completed his freshman year and then dropped out to accept a job as motion picture editor for the New York Evening Mail. In 1916, at the age of 24, he served as associate editor of Motion Picture News, one of the film industry’s leading trade journals. It was while toiling for the News that he began writing fiction on the side.

Worts sold his first story to The Argosy in 1917. It was published under the name Loring Brent because he didn’t want News editor William A. Johnston to know he was moonlighting. (Johnston, Worts recalled years later, “thought I fell asleep at my desk because I was working so hard for him!”)

When the income from his fiction writing surpassed his salary from Motion Picture News, Worts quit his job and began freelancing full time. The Argosy remained his top market but he also cracked the top slicks: Collier’s, Red Book, and the Saturday Evening Post all carried yarns by Worts. Yet it was work for the pulps commanded most of his time and effort.

“Peter the Brazen,” a six-part series published in late 1918 issues of Argosy, introduced the intrepid protagonist who became Worts’ best-remembered series character. Peter Moore was a ship’s wireless operator of unusual skill. Rumor had it he could “read a message in the receivers when the ordinary operator could detect only an indistinct scratching sound.” Although he was said to have worked all over the Pacific Ocean and in South America, Peter habitually manned a wireless on board the steamship Latonia, which sailed from the west coast of the United States to Hong Kong and ports south.

Like most pulp heroes Peter Moore had a knack for attracting women and trouble in equal measure. His first major adversary was the Gray Dragon, one of numerous Fu Manchu imitators who slithered across pulp pages in those days. The Dragon was summarily dispatched and late in 1919 Peter the Brazen returned to Argosy in “The Golden Cat,” this time pitted against the malevolent Fong-Chi-Ah, who coveted an ancient and fabulously valuable necklace adorned with a cat-shaped charm of gold.

Worts suffused his tales with atmosphere, painting vivid word-pictures with brief but pointed descriptive passages. He transported readers to the Orient with adventures that stretched the bounds of credulity yet captured the imagination of thrill-seeking readers. No one would mistake him for a great literary talent, but like the best pulpateers Worts was a gifted storyteller with a knack for grinding out page-turners with admirable regularity.

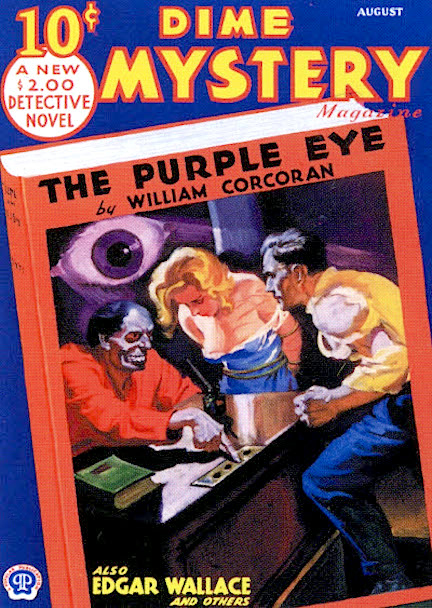

Peter the Brazen went into hibernation for a decade after appearing in “The Golden Cat,” but his creator returned to the pages of Argosy and its successor, Argosy All-Story Weekly, throughout the Twenties with stories of every type and genre. One of the more memorable was 1927’s “The Return of George Washington,” in which a great scientist claims to have found a method of regenerating human tissue from long-buried remains. His process is supposedly used on the skeleton of our first president, whose reappearance shocks a jaded nation. It all turns out to be a hoax, with “Washington” unmasked as a dull-witted hillbilly bearing an amazing resemblance to the nation’s father.

Worts revived Peter the Brazen in early 1930 at the behest of Argosy editor A. H. Bittner, who dusted off several long-dormant series characters, such as John Solomon and Semi-Dual, in a bid to recapture the allegiance of readers who had deserted the magazine. Peter Moore’s Thirties exploits were, if anything, more fantastic—but they crackled with action and excitement. He battled another Chinese master villain, the Blue Scorpion, in a trio of rapid-fire stories published between 1931 and 1933, and enjoyed many other adventures until 1935.

During this period Worts also wrote of slick lawyer Gillian Hazeltine and two-fisted Singapore Sammy Shay; the latter first appeared in Short Stories but eventually made his way into Argosy. These characters warrant further examination but will have to wait for a future blog post.

George F. Worts slowed down in the late Thirties, perhaps having finally exhausted his voluminous store of story ideas. Having married and divorced twice, he took a third wife and moved to Hawaii, doing public relations work and becoming a Collier’s correspondent during World War II. Worts returned to the States after the war and for a time lived in Arizona, editing Tucson magazine during the early Fifties. Unlike many of his fellow pulpateers, Worts invested wisely; his real estate holdings were extensive and provided him with enough income to travel widely. He died in 1968, leaving behind a dozen books and hundreds of stories now remembered only by pulp-fiction aficionados.

Overstock Sale for Serial Fans

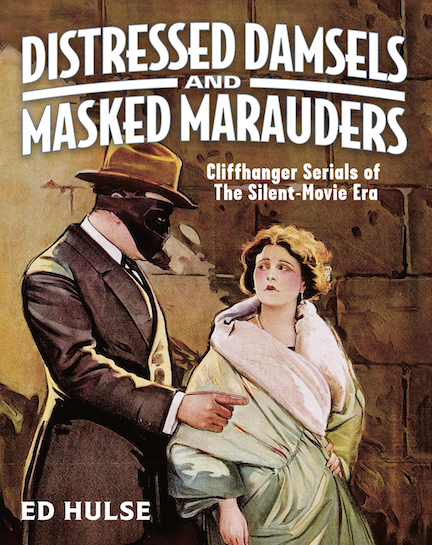

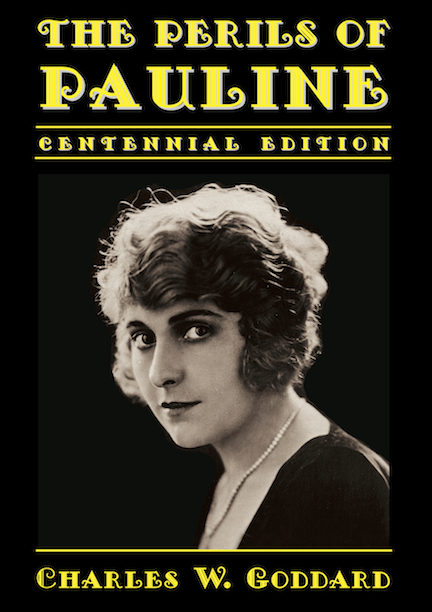

Recently I printed some extra copies of Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders and The Perils of Pauline: Centennial Edition for a Pearl White birthday commemoration organized by the Fort Lee Film Commission. Unfortunately, circumstances arising at the last minute prevented me from attending the event (which, I’m told, packed the venue), and as a result I’m in an overstock situation on these two books.

So for a limited time—a very limited time—I’m offering both books as a set for $40, shipping included, which represents a 20 percent discount. Distressed Damsels is the first book in my two-volume history of American movie serials of the silent-film era. The Perils of Pauline reprints the original 1914 novelization of the iconic chapter play, which made Pearl White an international star. The novel is preceded by my 5,000-word essay on the making of Pauline, a behind-the-scenes account every bit as interesting as the serial itself.

This offer is good only for as long as it takes to liquidate the sets I have on hand . . . and I don’t imagine that will be very long. You can order your own set here.

Rare and Unique Items Added to Collectibles Section

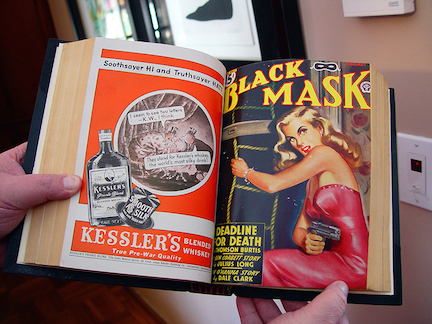

I’ve just added another batch of rare pulps and pulp-related books to the Collectibles For Sale section, including several bound volumes of the legendary Black Mask (previously owned by the magazine’s editor, Kenneth White), three collections of Johnston McCulley novelettes originally published in Detective Story Magazine, and a classic 1936 issue of The Shadow Magazine in high grade. And I’ve added a sharp copy of the first mass-market collection of Black Mask stories, The Hard-boiled Omnibus.

The Black Mask bound volumes include 18 consecutive issues from September 1943 through May 1946. The provenance alone should make these three books very desirable, but I realize that many collectors would be satisfied to own just one of them, so being in an experimental mood I’m also offering the third volume in the sequence by itself. If it sells before the lot of three, I’ll list the others singly as well.

Aside from being in exceptionally nice condition, the Black Mask books cover an historically important period in the magazine’s development. By this time Mask was no longer the hard-boiled, rat-a-tat-tat pulp edited by “Cap” Shaw; it had settled into a medium-boiled mode, with fairly orthodox murder puzzles solved predominantly by private eyes. Under Ken White the prose was no longer terse or chiseled, and the detectives often boasted amusing eccentricities. Leslie Charteris’ The Saint and Brett Halliday’s Michael Shayne are two of the well-known super sleuths found in these mid-Forties issues, many of which sport striking woman-in-distress covers painted by Rafael de Soto, a past master at this sort of thing.

The Johnston McCulley books, published by Street & Smith subsidiary Chelsea House, reprint the adventures of his popular series characters created for Detective Story Magazine: Black Star, The Spider, The Thunderbolt. These yarns, now difficult to find in their original pulp-magazine appearances, hardly match the quality of Black Mask fiction edited by Cap Shaw and Ken White, but they have many of the qualities of later hero pulps and therefore still have adherents today. The Chelsea House hardcovers are nearly as tough to find as Teens issues of Detective Story, and they’re almost impossible to get in jacket. The copies I’m selling, while well read, are perfectly sound, eminently collectable, and—in my opinion—fairly priced given their scarcity these days.

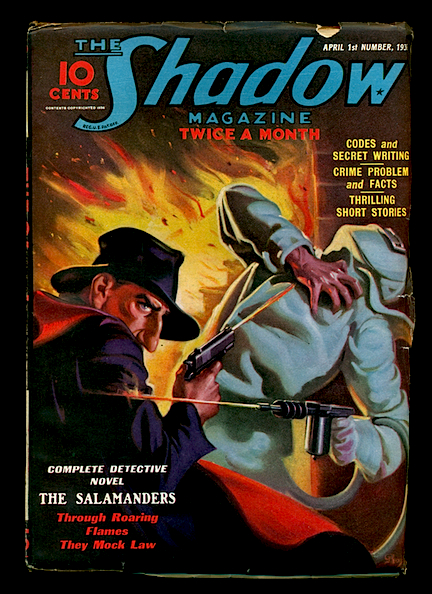

The April 1, 1936 issue of The Shadow Magazine carries one of the most memorable novels in the history of this long-running pulp. Reportedly, “The Salamanders” was commissioned by editor John Nanovic as a reaction to the action-packed adventures of the Spider, whose Popular Publications magazine was giving The Shadow some stiff competition. In my view, Walter Gibson was simply incapable of emulating Spider scribe Norvell Page, and while “Salamanders” was well received by faithful fans—ranking high in the first poll of reader favorites taken in 1937—it was by and large a one-off. Perhaps for that reason, and for the striking George Rozen cover, the April 1, 1936 number remains quite desirable. The copy I’m offering is a high-grade beauty marred only by a small chip in the front cover.

There’s still lots of good stuff available in the Collectibles section; check it out.

Speaking of Serials….

If you’re a film buff who spends a fair amount of time watching the Turner Classic Movies channel, you’re probably familiar with Flicker Alley. Originally a small boutique DVD label that offered rare and obscure silent films to hard-core collectors, they have broadened their activities to include full-scale restorations and marketing of archival gems sourced from around the world. Many of their efforts appear on TCM. Their latest project is an English-titled release of La Maison du Mystère (The House of Mystery), a 1923 French silent serial directed by Alexandre Volkoff and starring the distinguished Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine. Like many chapter plays produced in France during the silent era, Maison du Mystère eschewed the American model of fast action and daredevil stuntwork, preferring instead to tell its melodramatic story — which unfolds over an 18-year period— at a more leisurely pace. It’s a remarkable film, perhaps not blood-n-thundery enough for some tastes but extremely fascinating in its own right.

Flicker Alley asked me to be their most recent guest blogger and I’ve just filed a piece on silent serials,which you can read here under the title “Careers, Cliffhangers, and Commerce: The Serial’s Place in Film History.” I’m looking forward to their upcoming DVD release of Mystère, which will be previewed later this year at the Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention.

Rare, High-Grade Arkham House Titles and Other Pulp-Related Books Added to Collectibles Page

I’ve just added a slew of terrific pulp-related books to the Collectibles for Sale section, among them some avidly pursued Arkham House/Mycroft & Moran first editions. Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland, Lovecraft’s The Dunwich Horror and Others, Seabury Quinn’s The Phantom-Fighter, and Carl Jacobi’s Revelations in Black are just a few of these books, most of them in high grade and some like new.

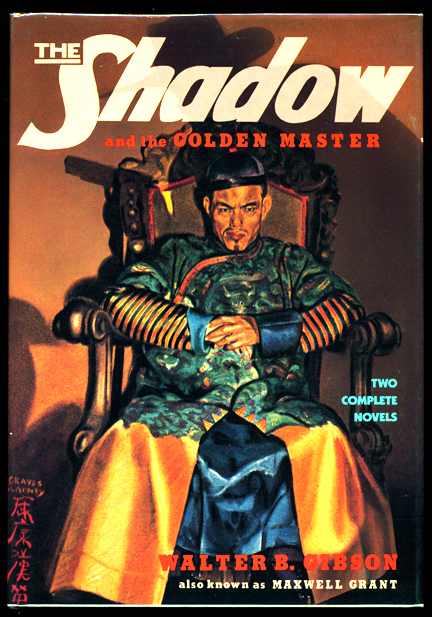

I’ve also listed a pristine copy of Mysterious Press’ 1984 hardcover The Shadow and the Golden Master, which reprinted the first two Shiwan Khan novels in facsimile with the original Edd Cartier illustrations and a new introduction by Walter B. Gibson.

You’ll also find a gorgeous copy of the definitive Hugh B. Cave collection, Murgunstrumm and Others, which reprints Hugh’s very best stories from the horror pulps. This copy is one of a limited number containing a bookplate signed by Cave and illustrator Lee Brown Coye.

Additionally, I have several unopened Girasol facsimile reprints of Terror Tales priced at $20 each; these sell for $35 from the publisher. If you’ve been curious about these great issues from the magazine’s sex-n-sadism phase, you can get them now for little more than half what they normally sell for.

Of course, I still have quite a few nice pulps and related items left from previous updates, and if you look carefully I wouldn’t be surprised bu that you’ll find something you’ve just got to have. Happy hunting!

Throwback Thursday: H. Bedford-Jones and THE WILDERNESS TRAIL

Exactly 100 years ago today, a fiction reader scanning the magazine rack at his local newsstand might very well have seen the February 1915 issue of Blue Book, one of the classic pulps. That particular issue was an important one, because it contained the debut story of a contributor whose name would become synonymous with the magazine’s title.

Today’s pulp-fiction devotees, born during the Baby Boom years (1946 to 1964), are too young to have bought rough-paper magazines on the newsstands and therefore gravitate primarily to those characters whose life spans were extended by Sixties paperback reprints and frequent appearances in other media: Conan, Tarzan, Doc Savage, The Shadow, and so on. Lester Dent, Walter B. Gibson, and Robert E. Howard are lionized in the fan press, and justifiably so. But they were not pioneers; they trod paths already well worn by the generation of pulpateers that preceded them. And of those, one loomed larger than most of his contemporaries.

Born in 1887, Henry James O’Brien Bedford-Jones spent his early months in Ontario, Canada, the family moving to Michigan when he was barely a year old. The future fictioneer showed an aptitude for writing as a public-school student, and he matriculated at Toronto’s Trinity College but dropped out after one year to pursue a career in journalism. As H. Bedford-Jones, he contributed to newspapers in Detroit and Chicago before turning his hand to fiction. His earliest short stories appeared in Frank A. Munsey’s pioneering pulp magazine, The Argosy, during 1909. He was not quite 22 years old when editor Matthew White purchased them. Published under the pseudonym “H. E. Twinells,” these initial efforts revealed him to be a born storyteller, if not a literary wunderkind.

Over the next few years Bedford-Jones threw himself headlong into full-time fiction writing, placing additional yarns with The Argosy and its sister pulp, The All-Story (later All-Story Weekly), as well as Street & Smith’s People’s Magazine, Top-Notch Magazine, and New Story Magazine. In a 1914 Argosy two-parter, “The Gate of Farewell,” he created what would become his most popular recurring character: John Solomon, the outwardly amiable, innocuous-looking Cockney who was actually a capable covert operative of the British government.

Of Bedford-Jones’ early output his biographer Peter Ruber had this to say: “His writing style during those years was remarkably fluid and polished; his imaginative storytelling ability far superior to many of his contemporaries, and a significant number of those stories are not as dated, nor the dialogue as stilted, as might be expected.”

Late in 1914 Bedford-Jones submitted a book-length novel to The Blue Book Magazine, an up-and-coming sheet published by Louis Eckstein’s Story-Press Corporation. Edited by Ray Long with the assistance of young Donald Kennicott, Blue Book was finally hitting its stride after several years of relative mediocrity. Long purchased the yarn from Bedford-Jones, beginning the author’s decades-long relationship with the magazine that would become his most reliable market. A rousing adventure set in early 19th-century America, The Wilderness Trail saw print in the February 1915 issue alongside tales by such popular fictioneers as H. Rider Haggard, E. Phillips Oppenheim, Ellis Parker Butler, and Albert Payson Terhune.

Over the next 34 years H. Bedford-Jones sold Blue Book an astounding 360 stories, including another five complete-in-one-issue novels and seven serialized novels. He was prolific in every genre but seemed to have a special affinity for historical adventures. Although he had no trouble selling to Long’s successor, Karl Harriman, it was Blue Book’s next editor, Donald Kennicott, who bought the most Bedford-Jones stories—some 280, of all lengths, between 1935 and 1949.

Having gone through a rough patch in the early years of the Depression (the inevitable consequence of failing magazines and reduced word rates), H. Bedford-Jones evolved the strategy of pitching editors not just individual yarns but entire series of stories with a central theme. In 1934 he simultaneously persuaded Kennicott and Short Stories head honcho Harry Maule to let him adopt this approach to the mass production of pulp fiction.

Blue Book’s February 1935 number offered the first installment of “Arms and Men,” a historical series that extended to 28 entries. Bedford-Jones followed this in 1937 with two more skeins, the self-explanatory “Ships and Men” and 17 Foreign Legion adventures collectively titled “Warriors in Exile.” In 1938 he launched what is arguably his best-remembered series for Blue Book. “Trumpets to Oblivion” combined fantasy, science fiction, and historical adventure. The premise involved a wealthy inventor’s perfection of a combination time machine and TV set—a device that reached back into the ether and retrieved images from past history. Each series installment opened with the inventor welcoming an audience to monitor the repeat “broadcast” of some famous event.

Bedford-Jones wrote 19 series for Blue Book, some of them overlapping, and until he died in 1949 each issue contained at least one and often two installments. They were published under his own name and also as by “Gordon Keyne” and “Captain Michael Gallister.” He occasionally turned out novel-lengthers for Kennicott as well, the most memorable of these being They Lived by the Sword, a fictional account of Hannibal’s army crossing the Alps. Remarkably, in addition to pounding out his Blue Book work, Bedford-Jones still found time to contribute regularly to other pulps, placing thematically linked series in Weird Tales and Short Stories as well.

An obituary published in the New York Herald-Tribune stated that H. Bedford-Jones earned more than a million dollars during his 40 years as a fiction writer. In King of the Pulps: The Life and Writings of H. Bedford-Jones (Ontario: The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2003), Peter Ruber estimated that the veteran pulpateer wrote a minimum of 25 million words. The true total may never be known, as Ruber allows that some yarns could have appeared under pseudonyms not yet attributed to the legendarily prolific author.

The Wilderness Trail is a seminal work in Bedford-Jones’ oeuvre. It not only kicked off his 34-year association with Blue Book but also was his first historical novel with an American setting. The author had a deep and abiding interest in the country’s post-Revolutionary War expansion and returned many times to the milieu he describes so well in this yarn. His employment of such real-life characters as Daniel Boone, Zachary Taylor, John J. Audubon, and the Indian chief Tecumseh is particularly skillful; we have no way of knowing if these historical figures ever interacted, but Bedford-Jones weaves the tale so cleverly that it’s easy to believe they did.

The novel is ambitious but never unwieldy. Its plot is straightforward, and seemingly random or divergent events are shown in the concluding chapters to have a critical bearing on the adventure’s climax. The story’s only failing—a minor one—is the awkwardness of romantic interludes featuring hero and heroine. The dialogue in these passages is stilted, which is surprising inasmuch as the exchanges between male characters have a natural ring.

Despite having been written relatively early in the author’s career, Wilderness Trail is a smooth, polished work with the unimpeded narrative drive that was a hallmark not only of H. Bedford-Jones, but of all popular and successful pulp fictioneers. Strangely, no American firm published it in book form, although the London-based firm of Hurst & Blackett Limited issued a British hardcover edition in 1925. Murania Press is both happy and honored to present to American readers this fine example of early pulp fiction, available in this country for the first time in nearly a hundred years. Why not take a chance on it? You can order it right here.

Birthday Boy: Sax Rohmer

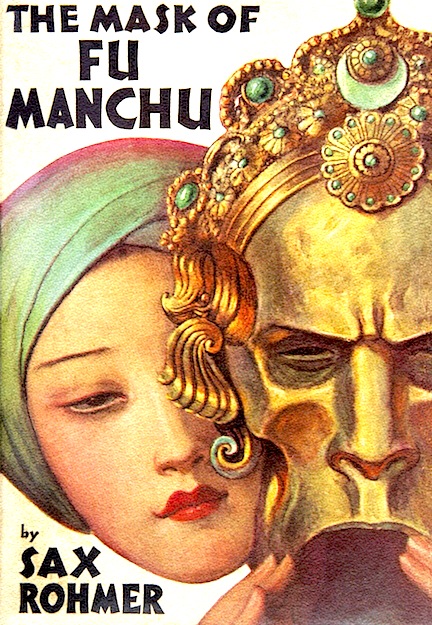

“Imagine a person, tall and lean and feline, high-shouldered with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan—a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with the all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present. Imagine that awful being and you will have a mental picture of Fu Manchu.”

The man whose birthday we celebrate today, the creator of the insidious Dr. Fu Manchu and writer of the above words, was born in 1883 as Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward. Raised in a working-class Irish Catholic family, he had a brief career in civil service but gave it up to pursue a life of letters. He wrote songs and comedy sketches for music-hall performers and sold his first short story, “The Mysterious Mummy,” to Pearson’s Magazine in 1903. After ghosting a fanciful 1911 autobiography of famous music-hall star Little Tich he turned to more sinister fare, drawing for inspiration upon his lifelong fascination with the East.

Rohmer later stated that his infamous “devil doctor” was loosely based on a Chinese master criminal operating out of London’s Limehouse district under the name of “Mr. King.” This engimatic figure reportedly controlled the opium trade and was backed by a powerful syndicate. Rohmer even claimed to have caught of a glimpse of the mysterious Mr. King one night in Limehouse: “A tall, dignified Chinese, wearing a fur-collared overcoat and a fur cap. . . . He was followed by an Arab girl wrapped in a grey fur cloak. I had a glimpse of her features. She was like something from an Edmund Dulac illustration to The Thousand and One Nights.”

“The Zayat Kiss,” a short story featuring as its villain one Dr. Fu-Manchu (the hyphen in his name was later dropped), was the first in a series of yarns published in England’s Cassell’s Magazine and in America’s Collier’s Weekly. In 1913 the British publisher Methuen collected the ten stories in book form as The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu; later that year the American firm McBride, Nast issued the tome here as The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu. The publication of these books gave Rohmer his first real taste of success. He penned a second series of Fu-Manchu short stories during the fall of 1914 and the winter of 1915—exactly one hundred years ago. These appeared first in the same periodicals and later, in book form, from the same publishers. Methuen titled the second book The Devil Doctor; McBride titled it The Return of Dr. Fu-Manchu. A third series was collected in 1917 by Methuen as The Si-Fan Mysteries and by McBride as The Hand of Fu-Manchu.

At that point the author put his most famous literary creation in mothballs. He had tired of Fu Manchu, just as Conan Doyle had previously tired of Sherlock Holmes and as Edgar Rice Burroughs would soon tire of Tarzan. But Rohmer continued to write stories, both short and long, suffused with Eastern mysticism. These yarns exploited his fascination with Egyptology and occult phenomena. Some Rohmer fans actually prefer them to the Fu Manchu tales. There’s no question that such books as Brood of the Witch Queen, The Quest of the Sacred Slipper, The Golden Scorpion,The Dream Detective, Grey Face, Yellow Shadows, and others have plenty to offer readers with a taste for Rohmer’s type of fiction. I love ’em all but am also partial to his 1930 novel, The Day the World Ended, a bizarre fusion of detective story, supernatural thriller, and science-fictional adventure.

As the Roaring Twenties ended, Sax Rohmer was rich and famous. He traveled to the East with his wife Elizabeth and enjoyed the fruits of his labors. Like many formerly struggling fictioneers who suddenly found themselves wealthy—including Edgar Rice Burroughs, Max Brand, and Edgar Wallace, to name just a few—Rohmer was a spendthrift. The money kept rolling in, but it rolled out even faster.

I’m convinced he was moved to revive the Devil Doctor after the critical and commercial success of The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu, a 1929 Paramount feature film starring Swedish actor Warner Oland (the screen’s future Charlie Chan) in the title role. One of the studio’s earliest all-talking pictures, it altered the character’s motivations and strayed considerably from Rohmer’s works but was a top box-office grosser. Previously Fu Manchu had appeared on screen only in a series of popular but undistinguished two-reel featurettes produced by England’s Stoll Picture Productions. I don’t believe they were ever released in America, so stateside audiences got their first look at the good doctor in Paramount’s film. It didn’t matter that paunchy, dough-faced Oland not in the slightest resembled the character as described by Rohmer; he had been playing sinister celestials in motion pictures dating back to 1916 and skillfully exuded the proper malevolence. Paramount quickly threw more money at Sax and had a sequel, The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu, in theaters less than six months later.

The impetus for a new Fu Manchu novel seems to have emanated from Collier’s editors. Rohmer biographer Cay Van Ash claims that their entreaties to Sax were made prior to the release of Paramount’s first film, but I doubt this. The Devil Doctor hadn’t appeared in print for more than a decade, except in A. L. Burt’s popular-priced hardcover reprints of the first three books, and while not forgotten he probably hadn’t been missed until Hollywood picked up on him. Given the 1929 film’s success, the character was now familiar to millions of Americans who’d never read the books, including a new generation too young to have seen the early short stories in Collier’s during the Teens.

Whatever the case, Rohmer complied and the magazine serialized Daughter of Fu Manchu during the spring of 1930; the following year Fu’s first book-length adventure was issued in cloth by Doubleday & Doran. It was ostensibly—but not really—adapted by Paramount that same year as Daughter of the Dragon. Warner Oland was back as Fu Manchu but the screenwriters killed him off early in the proceedings.

As the Depression and profligate spending took its toll on his finances, Rohmer during the Thirties turned increasingly to his most famous creation in a bid to stay solvent. It is this “middle” group of Fu Manchu novels I enjoy most: Mask of… (1932), Bride of… (1933), Trail of… (1934), and President Fu Manchu (1936). A friend of mine once described the key element of such yarns as “The Threat Of Death From Everywhere,” and that to me is their most endearing quality, the thing that makes them compulsively readable. These and other Rohmer books were published under the auspices of Doubleday’s Crime Club, which also was home to such popular fictional characters as The Saint and Bulldog Drummond.

You can see strain on the formula beginning in The Drums of Fu Manchu (1939) and continuing with The Island of Fu Manchu (1941), which varied the locales of the Doctor’s activities but lacked the sparkle of earlier series entries. Rohmer abandoned Fu Manchu for the duration of World War II but brought him back, now something of an anachronism, in The Shadow of Fu Manchu (1948), a weak installment novelized from an unsold play and dutifully published in magazine form by Collier’s and in book form by the Crime Club.

The atomic age found Sax Rohmer pretty well written out. During the Fifties he penned a series of mediocre novels (with occasional flashes of his old brilliance) featuring a female villain named Sumuru. He failed to interest Doubleday in these stories and they were published by Fawcett as paperback originals, as were his last two yarns featuring the Devil Doctor, Re-enter Fu Manchu (1957) and Emperor Fu Manchu (1959). They sold well, although the Sumuru books owed their success as much to the sexy covers as to the prose inside. Rohmer died on June 1, 1959.

Fu Manchu fared well on the silver screen, although filmmakers frequently took liberties not only with the doctor, but also his nemesis Nayland Smith and such supporting characters as Dr. Petrie, Inspector Weymouth, and especially Fu’s daughter, Fah Lo Suee. The Stoll shorts and Paramount features were followed by The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932 M-G-M) with Boris Karloff in the title role and Myrna Loy as Fah Lo Suee. Uncharacteristically lowbrow for a Metro production, it tinkered with Rohmer’s narrative and added elements of horror and science fiction not present in the original. But it’s great fun just the same. The characters returned in a 1940 Republic serial, Drums of Fu Manchu, which didn’t adapt the novel of that title but, rather, returned to Mask for its principal plot thread: the search for Genghis Khan’s tomb and the doctor’s subsequent representation of himself as the reincarnation of that leader. The serial, which starred Henry Brandon in the title role, also incorporated gimmicks and situations from earlier books in the series and was remarkably faithful to Rohmer’s vision. Its only transgression was the unnecessary killing-off of Fah Lo Suee. Drums was quite profitable and Republic contemplated making a sequel, only to pass when the U.S. entered World War II and China became our ally.

In Hollywood the character remained dormant throughout the Forties. An unsold 1952 TV pilot starred John Carradine as Fu Manchu and Cedric Hardwicke as Nayland Smith. Three years later Republic brought Rohmer’s Devil Doctor to the small screen in a short-lived (12 half-hour installments) and not terribly well done series titled The Adventures of Fu Manchu. The somewhat charismatically challenged Glenn Gordon played the eponymous evildoer, with Lester Mathews in support as Sir Nayland.

A full decade later, peripatetic producer Harry Alan Towers revived Rohmer’s creation is a series of color feature films with international casts and locations. British actor Christopher Lee took the role and made it his own; the sensuous Chinese actress Tsai Chin played Fu’s daughter, inexplicably renamed Lin Tang but every bit as venomous as Fah Lo Suee. The first Towers entry, The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), was undoubtedly the best. It co-starred Nigel Green as Smith and Howard Marion-Crawford as Petrie. In a brilliant bit of casting to capture the German audience, Towers cast Joachim Fuchsberger and Karin Dor in supporting roles. They were regulars in Germany’s krimi films adapted from the works of Edgar Wallace, whose thrillers shared many of Rohmer’s melodramatic plot devices. Face unreeled at the pace of an entire serial rolled into 90 minutes.

The immediate sequels, The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966) and The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), didn’t quite reach the mark set by the series opener, but they delivered more than their fair share of thrills and lived up to Fu’s promise, “The world shall hear from me again.” The latter film had a plum supporting role for Towers’ wife, the lovely Austrian actress Maria Rohm, who also appeared in the fourth entry, The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968). This film saw Richard Greene (former 20th Century-Fox contractee and TV’s Robin Hood) as Nayland Smith. He reprised the role in Towers’ last crack at the character, The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969). Both Blood and Castle were directed by Spanish filmmaker and current cult favorite Jess Franco, who had done several fine films for Harry Alan Towers. Sadly, his two Fu Manchu offerings were not up to the level of the three previous Towers-produced series entries, but Christopher Lee and Tsai Chin were still in fine fettle and one wishes the series had not ended when it did. (Towers also produced several Sumuru films, the last one released in 2003).

Reading Room: THE BLACK GANG

Herman Cyril “Sapper” McNeile, a British military engineer who saw combat during the First World War, turned to writing after the conflict and in 1920 began chronicling the exploits of one Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond, who would become one of pop culture’s most enduring heroes. Perhaps an idealized version of his creator, Drummond was the first of fiction’s many well-to-do WWI vets who, having become accustomed to action and danger during the War, found themselves bored and listless after returning to civilian life.

Like most vigilante heroes, Drummond is an unapologetic patriot with immense respect for the established order but equally immense impatience with the niceties of law enforcement and British jurisprudence. He’s inclined to favor direct action over legal wrangling and sees no problem in killing ruthless villains without due process. A born leader, he has gathered around him a group of like-minded friends—most of them also veterans of the Great War—who cheerfully match their wits and courage against a succession of crooks, traitors, and Bolsheviks operating to bring down Mother England. Drummond’s nemesis is the arch-criminal Carl Peterson, whom he bests for the first time in Bulldog Drummond, a 1920 novel received with equal enthusiasm on both sides of the Atlantic.

The second Drummond-Peterson bout takes place in The Black Gang, second novel of the series, published in the U.S. by Doran in 1922. This time around the action takes a pulpy turn. Although the British government privately applauds the work of Drummond and his cohorts, Scotland Yard takes a dim view of their activities. To safeguard their identities and thus guard against arrest and prosecution, Bulldog and his buddies begin wearing black masks and cloaks as they dash around the countryside. In addition to foiling Peterson’s plans, the black-clad vigilantes have taken to scooping up assorted malefactors and imprisoning them on a remote island off the coast of England. (Pulp fans will note that this predates similar practices later employed by The Shadow and Doc Savage.)

Peterson does not take kindly to this decimation of his ranks and strikes back by kidnapping Bulldog’s wife Phyllis. (Genius of crime that he is, Carl has quickly tumbled to the identity of the Black Gang’s leader.) But Drummond is one of those blokes who’s always at his best when things look worst, and this time is no exception.

I enjoyed The Black Gang a great deal. McNeile’s prose is clean-cut and vigorous, with a total lack of pretension or artifice. He’s a gifted storyteller whose defining trait is continuous forward motion, which is why his later novels were almost exclusively published in pulp magazines before appearing between hard covers. (Bulldog’s adventures splashed across the pages of The Popular Magazine, Detective Fiction Weekly, Mystery Novels Magazine, and Popular Detective.) His only failing is one not uncommon to Brits of a certain age and class: a clear disdain—if not outright hatred—for certain racial, ethnic, and religious groups deemed undesirable in early 20th century England. Russians and Italians are singled out for harsh treatment in The Black Gang, although Jews also take considerable abuse at the hands of Drummond and his compatriots. For this reason some people today find McNeile unreadable, but while such casual bigotry is grating to modern-day sensibilities, I’ve learned to read past the offending language and accept it as reflective of attitudes from a different time and place.

The Black Gang was adapted to the silver screen in 1934 as The Return of Bulldog Drummond, a British production starring Ralph Richardson in the title role. Although Richardson was an odd choice for the role, the movie is great fun—kind of like a 12-chapter serial boiled down to a 65-minute feature film.

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net