EDitorial Comments

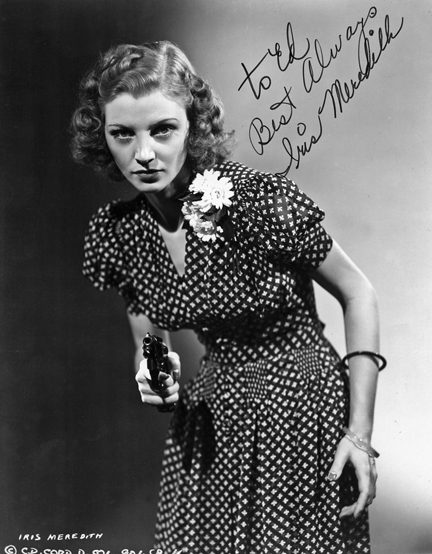

Birthday Girl: Iris Meredith

One of the most popular and frequently commented upon articles in Blood ‘n’ Thunder history is “My Dinner with Nita,” my tribute to Iris Meredith, the lovely actress who played pulp-fiction heroine Nita Van Sloan in a 1938 Columbia serial, The Spider’s Web. It first ran in issue #15 (Summer 2006) and was later reprinted in Blood ‘n’ Thunder’s Cliffhanger Classics. More recently it appeared as an interstitial piece in one of Anthony Tollin’s Spider pulp-reprint volumes. Since Iris was born exactly one hundred years ago today, I’m giving it some additional exposure: below you’ll find the complete text of “My Dinner with Nita.” I hope you enjoy it….

In the summer of 1976, I had an experience most serial fans could only dream of. I actually met, interviewed, and broke bread with the Spider’s paramour, Nita Van Sloan!

Not the real Nita, of course. That would have been impossible, because there wasn’t any real Nita. No, I attended a dinner with the reel Nita, the beautiful actress who played opposite Warren Hull in The Spider’s Web (1938), first of two fast-action Spider chapter plays made and released by Columbia Pictures.

Her name was Iris Meredith, and she had come to Nashville, Tennessee as a guest of the Fifth Annual Western Film Fair, a movie-buff confab sponsored by Western Film Collector magazine. Over the course of this four-day convention, some 160 feature-length films and a couple dozen serials—among them The Spider’s Web—unspooled in six makeshift screening rooms outfitted with 16mm projectors manned by bleary-eyed collectors. Movie showings began at 10 a.m. every day and continued until the wee hours of the next morning. The hucksters room included well over a hundred tables, some of them covered with boxes full of vintage-movie memorabilia, others sagging beneath the weight of film cans containing 16mm prints. Film Fair attendees could either screen themselves blind or spend themselves poor. Some did both.

Much-needed diversions were provided by panel discussions (in which the many guest stars reminisced about filmmaking in the Good Old Days) and the Saturday-night awards banquet, when actors long forgotten by the public at large accepted handsome plaques and standing ovations from True Believers who still cherished the Saturday-matinee movies of their youth.

I had already attended several such events and would likely have returned to Nashville even if Iris Meredith hadn’t been among the dozen or so performers invited to this year’s convention. But her presence was the icing on the cake for me. To think I’d be meeting the silver screen’s one true Nita Van Sloan! (Those of us who had seen both Spider serials rarely spoke of The Other, that brassy, garish floozy so obviously miscast in the 1941 sequel, The Spider Returns. As far as we were concerned, Iris Meredith was Nita. Period.)

Born on June 3, 1915 in Sioux City, Iowa, Iris Shunn didn’t have an easy childhood. By the time she was 10, her family had moved twice, first to Minnesota and then to southern California. By the time she was 13, both parents had died, leaving her to support three younger siblings with a Depression on the way. She attended school in the morning and toiled as a theater cashier in the afternoon and evening. Legend has it that Iris was discovered by a talent scout while working at the Loew’s theater in downtown Los Angeles. Still just a teenager—albeit a beautiful one—she briefly joined the fabled Goldwyn Girls and first appeared on screen with them in a 1933 Eddie Cantor vehicle, Roman Scandals.

Iris worked as a chorus girl in several movie musicals before landing her first substantial part: an ingénue role in The Cowboy Star (1936), a better-than-average “B” Western in which she played opposite Charles Starrett for the first time. (This film was the first in which she received on-screen billing, and for it she assumed the Meredith surname.) Starrett, scion of a wealthy northeastern family, had taken up acting while attending Dartmouth College. He never really caught on with adult moviegoers and in 1935 began starring in low-budget horse operas released by Columbia. He spent 17 consecutive years making Westerns for that studio, appearing exclusively as The Durango Kid from 1944 to 1952.

When Iris landed a Columbia contract, she was initially assigned to the unit cranking out Charlie’s pictures, and she co-starred with him in some 19 Westerns released between 1937 and 1940. The Starrett vehicles of this period maintained a fairly high standard, but their strict adherence to formula made one virtually indistinguishable from another. The Sons of the Pioneers, a Western-music group to which Roy Rogers once belonged, worked with Charlie and Iris in every picture. The supporting casts nearly always included Dick Curtis as the principal heavy and silent-screen veteran Edward Le Saint as either Starrett’s or Meredith’s father. Even the bit players were the same from picture to picture, and they almost always wore the same clothes. For that matter, so did Iris: She generally showed up in an ensemble consisting of plaid shirt with vest and split skirt.

Iris lobbied for parts in better movies but rarely escaped confinement in the Western and serial unit headed by producer Jack Fier. When she did, it was only temporarily and usually in a thankless role. In late 1940, after appearing in 22 Westerns and three serials, she left Columbia. For the next couple years Iris freelanced, finding it difficult to land roles outside of Hollywood’s Poverty Row. By 1943 she had married director Abby Berlin, himself a Columbia contractee; shortly thereafter she had a daughter and settled into domestic life.

Unlike some of her contemporaries, Iris never attempted a comeback when television series production created new opportunities for technicians and performers used to working at top speed on short budgets. She never dreamed that people still remembered her fondly, or that she had won new fans thanks to TV reruns of her old movies and the proliferation of 16mm dupe prints of the old Westerns. By the mid Seventies, however, the word was out. The “B”-Western stars, starlets, and supporting players were very much in demand at nostalgia-oriented film festivals, and Iris eventually accepted an invitation to appear at one such event.

Of course, those of us who attended that 1976 Western Film Fair had no way of knowing what hell Iris Meredith had been through. Some ten years earlier she had been diagnosed with oral cancer. She endured 14 operations, surrendering part of jaw and tongue in her fight against the disease. None of us expects our film favorites to withstand indefinitely the ravages of time, but we weren’t fully prepared for the severely disfigured, prematurely aged woman who courageously greeted her fans.

However shocked Film Fair attendees may have been, they never let on. Iris bravely met and talked with all of us, laboring mightily to make herself understood. Losing part of her tongue made it impossible to clearly articulate certain words, and her slurred speech was reminiscent of someone who’d had way too much to drink.

But ultimately this didn’t matter to us, and our outpouring of love plainly lifted her spirits. As the convention progressed Iris seemed demonstrably happier; by the second or third day one could see a twinkle in her rheumy eyes. Initially reluctant to speak, she pushed herself to engage fully with fans who approached her with questions as well as stills and lobby cards for her to sign.

She was accompanied by her grown daughter, who occasionally sat with her mom when Iris elected to watch one of her old movies. About halfway through a screening of The Spider’s Web—all 15 chapters in one marathon session, interrupted only by the projectionist’s reel changes—the daughter excused herself, leaving Iris alone. The screening rooms were sparsely attended at that moment; my recollection is that another guest-star panel was just getting underway. Only a dozen or so people remained to see the Spider battle his arch-foe, the Octopus, to a standstill.

A few rows behind and to the right of Iris, I stared at the erstwhile actress as the next episode began. She sat very still and straight, apparently transfixed by the flickering image of a younger, beautiful version of herself. I couldn’t help but wonder what might be going through her mind. Having already seen the serial several times, I left after one more chapter to attend another screening. As I eased through the screening-room door I shot a glance back at her. She was still riveted by the adventures of Dick, Nita, and the others.

On the third day of the convention, I persuaded Iris to sit for an interview. We adjourned to a small meeting room down the hall from the massive ballroom that housed dealers and other stars. She briefly stiffened when I brought out my portable cassette recorder, but after a few seconds—just as I was about to stuff it back into my briefcase—she relaxed again. “What would you like to know?” she asked.

Naturally, I was most eager to hear whatever she had to say about The Spider’s Web. “You know,” she said, “a year ago I couldn’t have told you anything about it. But now that I’ve seen it again, little things come back to me.

“Those serials were very hard to do. With the Westerns, you worked for a week or two and then you had time off. But those damn serials went for four, or five, or six weeks at a time. And we worked very long days, sometimes 12 or 14 hours. So every night you came home exhausted. It was all we could do to remember our lines the next day. The directors had it bad because they had to keep track of everything, all those little things that happened in the chapters.”

I asked her what she remembered about her castmates.

“Well, of course, I knew Richard Fiske already. We worked together on some of the pictures I did with Charlie [Starrett]. Warren Hull was a dear. Between takes he was a great kidder. And he loved to sing. He had a lovely voice. But then we would get in front of the camera and he would get so serious and squint, you know, and start shooting at people.

“I remember we all thought it was funny that Kenny Duncan was playing this Hindu [Ram Singh]. He was Canadian! And they gave him some of the craziest lines to say.” (I imagined Iris referred to Ram Singh’s snarling threats, like my favorite: “Dog with a pig’s face! If I had my knife, I’d carve my name in your heart!”)

“The other thing I enjoyed was that I got to wear nice clothes. I only had a few changes of wardrobe, but it was so much fun to wear nice dresses after doing all those Westerns in that damn split skirt. And of course, in the Spider film I didn’t have to deal with horses.”

Iris insisted, as had so many serial actors before and since, that she barely remembered making the chapter plays. “Really, we were rushing around so much we didn’t know half the time whether we were coming or going. The scripts were as thick as telephone books and every night I only memorized as many lines as I needed for the next day. We didn’t shoot the chapters separately, it was all done according to where on the back lot we were scheduled to be on any given day. Or on which set; we did many scenes on sets that had been built for other movies. I still wonder how the production managers kept things straight [during the making of a serial].”

She did, however, have specific memories of Overland with Kit Carson, the 1939 serial she did with newly minted cowboy star “Wild Bill” Elliott. “We went to Utah to shoot most of it,” she told me. Then she tried to pronounce the name of the town where the company stayed while on location, but I couldn’t understand what she was trying to say. Finally she scribbled the name on my note pad: “Kanab.” Several Westerns were made in and around that community, which the town fathers hoped would attract Hollywood producers in greater numbers. A Western street was built in the area to make Kanab a more appealing location for filmmakers; Overland with Kit Carson was the first production to utilize it.

Iris was fond of her Kit Carson co-star, with whom she also made three feature films. “Bill Elliott took his work very seriously,” she said. “The first picture I made with him, he wasn’t much of a rider yet. But he always practiced between takes. He got to be very good at it. And you know how he wore his guns, backward in the holsters? Well, he spent hours practicing a quick draw with those guns. I really admired him for working so hard to be convincing.”

She also had kind words for Ed Le Saint, another member of the Starrett stock company. “He was such a dear man. Very kind to me. But, you know, he was so old! I could never understand why they cast such an old man to play my father. Really, he was old enough to be my grandfather.”

By this time Iris seemed to be enjoying herself. She was no longer self conscious about the tape recorder, or about the effort it took to pronounce certain words. But I inadvertently brought our chat to an awkward halt with my next question:

“In 1940 you did your last serial, The Green Archer, for one of your Spider’s Web directors, James W. Horne. What do you remember about that film?”

Her face clouded and the spark went out of her eyes. She seemed more than a little sad as she quietly replied: “I don’t want to talk about that film. Please don’t ask me about it.”

I was stunned. What on earth could have happened during the making of that serial to elicit such a reaction? Fortunately, Green Archer was the last film about which I’d wanted to ask, and with nothing else to say I cleared my throat nervously and mumbled, “Well, I think we’re pretty much covered everything.” I thanked her, she thanked me, and as I got up from the table I could see several dozen fans milling outside in the hall, waiting for a chance to say hello and get her autograph.

That night at the banquet, following the typical rubber-chicken dinner, Iris Meredith was one of a dozen people presented with the inscribed plaque traditionally given to Western Film Fair guest stars. As she made her way to the podium, every person in the ballroom rose to give her a lengthy standing ovation. It was our way of honoring her for the courage and grace she had exhibited during the show. The room fairly crackled with electricity. Even from where I was, some ten feet from the dais, I could see her eyes welling up with tears. When the applause died down, she said just two words: “Thank you.” Then, as it swelled again, she took her seat and stared intently at her award, as if embarrassed to make eye contact with her adoring fans.

Subsequently Iris Meredith attended another film festival, but she never became a regular on the “nostalgia circuit,” as did some of her contemporaries. She continued her struggle with cancer, but the disease eventually overtook her. Not yet 65 years old, Iris died on January 22, 1980.

In 40 years of convention-going, I’ve met dozens of the actors, writers, directors, and stuntmen who worked on my favorite serials, Westerns, and “B” movies. I’ve enjoyed my encounters with all but two or three of them. But none ever affected me quite the way Iris Meredith did. It’s difficult to explain, but even now, decades later, I get a little thrill whenever I revisit The Spider’s Web and gaze at the optical player credits—you know, those glimpses of the principal actors with their names splashed across the bottom of the frame. Iris always stands there, clad in Nita Van Sloan’s flying togs, smiling sweetly and placidly even though she will shortly find herself menaced yet again by the minions of the Octopus.

In those moments, I like to pretend she’s smiling at me.

4 thoughts on “Birthday Girl: Iris Meredith”

Leave a Reply to Richard Sereci Cancel reply

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net

Nice job Ed. Really enjoyed the article. Have seen her in a ton of Starrett westerns (have all available) & the serials tool. Did you ever find out what happened on The Green Archer that made her so upset?

Al

Very nice ,do you still have the tape from that interview? Would love to hear my grandmother’s voice.. Was 4 or 5 years old when she was diagnosed with cancer so that’s the only voice I remember. thank you.

Real nice article on my alltime favourite b western actress.Having been a kid of the 40’s I have

comtinued my love of B westerns all these years.I write articles for the 48 year old British B western magazine

“Wranglers Roost” one of which was one

on Iris &I included a photo of that 1976 Nashville convention,Together with the editor,Colin Momber of “Wranglers Roost” we visited in 1984 with Charles Starrett at his home at Laguna Beach.He spoke glowingly of Iris “a great gal,but smoked too much”.She made 20 B westerns wih Charles,but sadly so many of them have never been made available to the public.

She was so right about Ed Le Saint,

he was too old looking to play the

heroines father,born in 1870 he looked more like a grandfather in his

18 appearances in the Starretts 1935-1940.

Thanks again for delivering us such a

memorable recollection of Iris.

Somehow you have already posted my comment