EDitorial Comments

Birthday Boy: Clarence E. Mulford

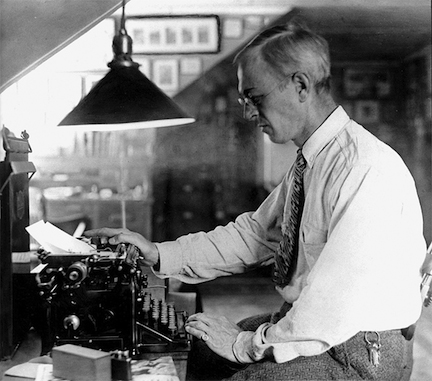

Western fiction’s most enduring hero was the offspring of a mild-mannered, bespectacled civil servant who spent his leisure hours writing about a mythical frontier from the confines of a modest Brooklyn apartment. The author was Clarence Edward Mulford, and the literary figure he sired was Hopalong Cassidy. Hoppy and his Bar-20 comrades first appeared in a short story, “The Fight at Buckskin,” published in the December 1905 issue of Outing Magazine. Today we celebrate the birthday of that prolific writer, whose work mostly (but not exclusively) appeared first in pulp magazines.

Born on February 3, 1883 in Streator, Illinois, Clarence Mulford grew up in a solidly middle-class household. Small of frame, quiet, and introverted, Clarence was an indifferent student with limited social skills and a disdain for athletics. His principal interest was the Wild West—or, at least, the Wild West depicted in the lurid dime novels of that era. He read in prodigious quantities the almost wholly fictitious exploits of Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, and Kit Carson, living vicariously through their adventures. After graduating from high school he toiled in several humdrum jobs before finding steady work as a civil servant, dispensing marriage licenses in Brooklyn, New York.

As a young man Mulford was animated by two passions: physical fitness and writing. Weight training and roadwork developed his undersized body; putting pen to paper developed his mind. “The Fight at Buckskin” wasn’t the first story he wrote, but it was the first he sold. This 6,250-word yarn introduced Outing readers to the scrappy cowpunchers of the Bar-20, a Texas cattle ranch managed for an Eastern syndicate by foreman Buck Peters. His loyal “waddies” included Red Connors, Johnny Nelson (also known as “the Kid”), Lanky Smith, Skinny Thompson, Pete Wilson, Billy Williams, and a particularly colorful gent known as Hopalong Cassidy.

The Cassidy of Mulford’s early stories is a raucous cowboy whose habits certainly wouldn’t make him welcome in polite society. He’s an inveterate tobacco chewer (and spitter) prone to swearing and fond of concocting creative insults good-naturedly directed at his fellow punchers. Described in an early story as “passably good-looking,” Hopalong sports a thatch of unruly red hair and typically wears the faded denims, chaps, and broad-brimmed sombreros common to working cattlemen. He can be volatile now and then, but for the most part he’s a cool character with a keen mind and a general’s sense of strategy. Like all his comrades at the Bar-20, he puts a high premium on loyalty. “The Fight at Buckskin” revolves around an all-day gunfight occasioned by the killing of one Jimmy Price, Buck’s youngest puncher.

Although Mulford was not a particularly distinguished writer—his prose was often stiff and formal, as per the Victorian style prevalent in the early 20th century—his Bar-20 yarns had the ring of authenticity. His early interest in the Wild West of dime novels had metamorphosed into a fascination with Western history, and he built a reference library that consisted not only of books written about the frontier, but also a library of file cards bearing data he gleaned from countless magazine articles and newspaper accounts. (Eventually he amassed more than 17,000 file cards, the largest such collection ever assembled by a single researcher.)

Mulford’s tales were accurate with regard to history, location, and the minutiae of ranch life, but the principal characters in the Bar-20 saga bore little resemblance to real working cowhands in the late 19th century. From the first, Hoppy, Buck, and the others were mythical figures comparable to Odysseus and his adventurers, or to the knights of Arthurian legend. Hardly perfect men, they nonetheless adhered to a rigid moral code and used violence primarily to achieve rough justice in a region of the country not yet bound by the rule of law.

For several years following publication of “The Fight at Buckskin,” the Bar-20 saga unfolded in short stories. In June of 1907, Mulford began writing his first novel-length installment in the series. He discarded two drafts before completing the manuscript in March, 1909. Hopalong Cassidy was published exactly one year later by Chicago’s A.C. McClurg & Co. The novel focused on the feud between the Bar-20 and an adjoining ranch, the H2, with a subplot detailing Hopalong’s romance with Mary Meeker, mistress of the rival cow outfit. Lengthy, episodic, and packed with supporting characters, the book didn’t overly impress critics but achieved considerable success nonetheless; McClurg went through six hardcover printings in the first year alone.

Mulford gradually eased up on short-story production and concentrated on cranking out book-length yarns. Hoppy wasn’t always the focal point of these; Buck Peters, Johnny Nelson, and reformed gambler Tex Ewalt (an early antagonist of the Bar-20) each “starred” in novels using their names in the titles. In 1923 Mulford transferred his allegiance from McClurg to Doubleday, and that house published his subsequent novels in hard covers after serializing most of them in its pulp magazines Short Stories and West. While not blockbuster best-sellers, Mulford’s books attracted a fairly large, faithful following that guaranteed consistent sales for Doubleday. Over the years the New York-based publishing house developed a warm relationship with Mulford, which directly resulted in Hopalong Cassidy being brought to the silver screen. Readers of this blog, Blood ‘n’ Thunder, and my other publications know how fond I am of the Hoppy films, which have been discussed in this space before and doubtless will be again.

A staunch small-government conservative, Mulford hated paying a huge percentage of his earnings in income tax, so after completing Hopalong Cassidy Serves a Writ in 1941 he stopped writing altogether. Royalty payments on his books and licensing fees from Hollywood enabled him to live comfortably, and in fact he became wealthy in the early Fifties from his small percentage of the revenue generated by sales of licensed Hopalong Cassidy consumer products. Ever the prudent steward of resources, Mulford continued to enjoy a modest lifestyle. He died in 1956 at age 72.

Mulford’s fiction shows its age more so than the works of many contemporaries. But he remains readable, and at their best his yarns have about them an almost magical aura. The Hoppy about whom he wrote is a larger-than-life figure despite the author’s efforts to make him seem like an ordinary cowhand with a good head for strategy. In recent years several early Bar-20 books have been reprinted in paperback, and I recommend them to fans of pulp fiction in general and Westerns in particular.

3 thoughts on “Birthday Boy: Clarence E. Mulford”

Leave a Reply to Al Stone Cancel reply

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net

Hi Ed,

Thanks for the great article. Really enjoyed it. I read a couple of the Hoppy books several years ago, but really found them too slow. Then I read the Louis Lamour Hoppys in paperback & enjoyed them. Just recently I found a Forge Pub. paperback released in 2014 of Hopalong Cassidy, and Bar 20 Days in one book. Tried angain & enjoyed them juch better this time. And I too loike the Hoppy movies, now that I’m older – especially his earier ones.

Al Stone

Ed, Thanks this is a fine article on Clarence. I grew up in the ‘50s listening to the Boyd version of Hoppy and only recently discovered a reprint of the Bar20 Three in a Junk store and am thoroughly enjoying the “real Hoppy” I grew up in the West Colo. NM and Az and it is refreshing to learn about Mulford’s take on western characters. I also like his way he has the cowboys speak, authentic I would think?

You stated that he compiled the most comprehensive catalog of Western info, do you know if he traveled there as well ? Thanks, Nelson

Nelson, after Mulford moved to Fryeburg, Maine, I don’t believe he did much traveling other than the occasional trip to New York to see his editors at Doubleday. Which means he never got any farther west than the small Illinois town in which he was born.