EDitorial Comments

2019 Windy City con’s Film Program: Saturday schedule

10:00 a.m. — THE LEOPARD MAN (1943), 66 minutes.

Adapted from “The Street of Jungle Death” (Strange Detective Mysteries, July-August 1939), revised and expanded into the novel Black Alibi by Cornell Woolrich.

Cornell Woolrich’s output—novels and pulp stories combined—was the basis of a good many classic “B” movies and films noir. We’ve already run some of the more obscure; this one is better known and commercially available. But The Leopard Man is such a crackerjack little picture that, after revisiting it at home a couple months ago, we couldn’t resist slotting it into this year’s film program.

The black leopard employed in a nightclub act escapes during an engagement in a small New Mexico town. Following the death of a young girl at the beast’s claws, a posse is formed to hunt the man-killer. Other victims fall prey to the leopard and suffer similarly gruesome fates. Press agent Jerry Manning (Dennis O’Keefe) and his client Kiki Walker (Jean Brooks), for whose act the leopard was rented, are devastated to have been the unwitting cause of this reign of terror. But then evidence surfaces that human agency might be behind the grisly murders. . . .

Third of nine stylish low-budget films produced for RKO by Val Lewton, The Leopard Man was directed by Jacques Tourneur, who also helmed Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), the unit’s previous sleeper hits. Made in just four weeks on a budget of less than $150,000, this third Lewton offering exhibits the same ingenuity in maximizing thrills while minimizing expenditures. Robert de Grasse’s cinematography, utilizing clever lighting effects to create an atmosphere of nocturnal terror, can reasonably be characterized as “virtuoso,” and Mark Robson’s editing sustains a measured pace while heightening tension during sequences that depict the stalkings and murders. You’d be hard pressed to find a more suspenseful 66 minutes in any motion picture of the era.

11:15 a.m. — HIGH TIDE (1948), 72 minutes.

Adapted from “Inside Job” (Black Mask, February 1932) by Raoul Whitfield. Reprinted in The Hard-Boiled Omnibus (Simon & Shuster, 1946).

An obscure “B” movie released by humble Monogram Pictures, one of Hollywood’s smallest studios, High Tide some years ago was “rediscovered” by film noir cultists who proclaimed the modest thriller an unjustly neglected work. It had come to our attention in the early 1970s with the private screening of an old, worn 16mm TV print. At that time. though, we were unaware of the original story’s pulp origin.

The narrative gets underway at night, showing us a wrecked car on a beach. One passenger, newspaper editor Hugh Fresney (Lee Tracy), has broken his back in the crash and is immobile. The other, private detective Tim Slade (Don Castle), is pinned beneath the vehicle. Both are certain to drown as the high tide sweeps in. Helplessly awaiting their finish, Fresney and Slade reflect on the strange circumstances that brought them to this point.

Although lacking the bravura visual style of noir classics like Phantom Lady or Out of the Past, High Tide has the archetypal characters familiar to genre devotees: the sultry femme fatale, the cynical private eye, the hapless fall guy, the brutal crime boss, the scheming “big shot” cloaked in wealth and prominence. The narrative is well developed, although noir fans doubtless will figure out what’s going on long before Robert Presnell’s screenplay spells it all out. But this is a taut, compelling film, and one of the very few adapted from a non-series Black Mask yarn.

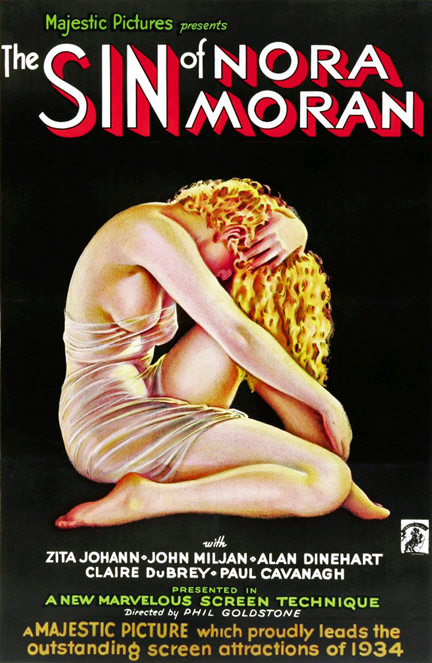

12:30 p.m. — THE SIN OF NORA MORAN (1933), 65 minutes.

Adapted from “Burnt Offering” (The Underworld, August-October 1930) and “The Woman in the Chair” (Complete Underworld Novelettes, Summer 1932) by Willis Maxwell Goodhue.

Nora Moran has an odd pedigree. Its plot was originally developed for a 1930 pulp novelette that the author, playwright Willis Maxwell Goodhue, subsequently used as the basis for a stage drama, The Woman in the Chair, making significant changes in the process. Then, using the play as inspiration, he composed a new prose version and sold it to another rough-paper magazine! Goodhue primarily wrote breezy comedies for the stage, and Nora Moran was not just his sole property adapted by Hollywood, but also his only melodrama.

Convicted of a murder she did not commit, Nora Moran (Zita Johann) is executed—the first woman in her state to die in the electric chair for 20 years. Her sad story unfolds in a series of flashbacks and hallucinatory interludes, with additional explanation provided by District Attorney John Grant (Alan Dinehart).

Sin of Nora Moran reached the screen as a vanity project undertaken by independent producer Phil Goldstone, who attended a performance of the Goodhue play and saw in it a potential showcase for actress Zita Johann (best known for her role in Boris Karloff’s 1932 horror hit The Mummy), with whom he was infatuated. Goldstone, a highly successful businessman, was best known in Hollywood as a money lender who supplied short-term loans to cash-strapped studios during the Great Depression’s darkest days. A dilettante filmmaker, he not only earned interest on his money but as a courtesy was loaned popular contract players for key roles in his Poverty Row productions. During principal photography Goldstone replaced original director Howard Christie after becoming convinced that the latter wasn’t effectively utilizing his stage-trained star.

Using the then-daring “narratage” technique—which relied on a series of non-chronological flashbacks knitted together by a narrator—the bizarre, morbid Nora Moran today is considered Poverty Row’s meisterwerk, a characterization we’re not prepared to refute. See it and judge for yourself.

1:45 p.m. — FAST AND LOOSE (1939), 80 minutes.

Adapted from “Fast and Loose” (Argosy, February 25-March 25, 1939) by Marco Page [Harry Kurnitz].

“Marco Page” was the pseudonym employed by critic and journalist Harry Kurnitz for his 1938 whodunit Fast Company, winner of that year’s “Red Badge Detective” contest sponsored by Dodd, Mead & Company. In addition to collecting the thousand-dollar prize, Kurnitz saw his first novel published by Dodd, Mead and quickly optioned by M-G-M, which rushed a film version into production. A murder mystery set in the rarified world of high-end bibliophiles, Fast Company had as its reluctant sleuths the rare-book dealer Joel Glass and his wise-cracking wife Garda. Metro, looking to duplicate the success of its popular “Thin Man” series, cast second-tier stars Melvyn Douglas and Florence Rice in the leads, changing their characters’ surnames from Glass to Sloane.

While not exactly a runaway hit, the Fast Company movie did well enough to justify a sequel, so M-G-M commissioned Kurnitz to write one. In a concession previously granted pulp favorite Max Brand, then providing stories for the studio’s Dr. Kildare pictures, Kurnitz was allowed to sell a prose version of his screenplay to Argosy, which serialized “Fast and Loose” just as the resulting movie was playing its first-run engagements. Unlike the original novel, it never saw print in book form.

The sequel once again embroils Joel and Garda (now portrayed by Robert Montgomery and Rosalind Russell) in a bibliomurder, this one revolving around the theft and potential forgery of a Shakespeare manuscript. The dramatis personae include a shady millionaire, his wastrel son, his trusted broker, an eccentric supermarket tycoon, and a crooked nightclub owner.

The Kurnitz screenplay doesn’t quite reach the mark set by Fast Company. Nor can we honestly say that Montgomery and Russell match Douglas and Rice in their portrayal of the Sloanes. The first film’s stars were relaxed and breezy; the second’s somewhat less so. Their byplay seems forced and ever so slightly inauthentic. Nonetheless, Fast and Loose moves briskly and is a slick, entertaining programmer.

3:15 p.m. — THE SHADOW (1940), Chapters Eight through Fifteen, app. 160 minutes.

Partially adapted from the Shadow Magazine novels “The Green Hoods” (August 15, 1938), “Silver Skull” (January 1, 1939), “The Lone Tiger” (February 15, 1939), and the Shadow radio episode “Prelude to Terror” (January 29, 1939) by Maxwell Grant [Walter B. Gibson].

In these final eight episodes The Shadow’s struggle with the Black Tiger reaches a shattering climax—but not before there’s been plenty of laughs and fast-paced action.

Immediately following Saturday auction — CHEROKEE STRIP (1937), 56 minutes.

Adapted from “Cherokee Strip Stampeders” (New Western, October-November 1936) by Ed Earl Repp.

A burly, red-headed baritone from New Jersey, erstwhile band singer and radio vocalist Dick Foran played small roles in a handful of Fox films (including Shirley Temple’s first starring vehicle, Stand Up and Cheer) before signing a long-term contract with Warner Brothers in 1935. The studio had just decided to reenter the horse-opera market and was about to begin production on a low-budget oater titled The Boss of the Bar-B Ranch. But surprising audience reaction to a warbling Westerner named Gene Autry—seen in a 1934 Ken Maynard picture titled In Old Santa Fe and boosted to stardom in The Phantom Empire, a Western serial with science-fictional trappings—persuaded Warners to enter the singing-cowboy sweepstakes.

Boss of the Bar-B Ranch was retitled Moonlight on the Prairie and slightly rewritten to accommodate two songs performed by newly minted star Foran. Given better-than-average production mounting, Moonlight elicited generally favorable reviews and satisfied audiences. Foran’s acting left something to be desired, although his dime-novel dialogue and caricaturish Texas accent was partially to blame. In subsequent Westerns he delivered relaxed performances, although his robust vocal style always seemed more appropriate to the stage than to the sage.

Cherokee Strip, a reasonably faithful adaptation of Ed Earl Repp’s pulp novelette, has as its background the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 and casts Foran as a frontier lawyer who comes to the aid of homesteaders being victimized by cattle rustlers. At a negative cost of approximately $99,000 it was by far the most expensive of the star’s 12 “B” Westerns, but also one of the most successful. The film’s box-office fortunes were heavily skewed by the surprise Hit Parade success of its featured song, “My Little Buckaroo.”

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net