EDitorial Comments

2018 Labor Day Weekend Sale

Beginning Friday at 12:01 a.m. and continuing through Monday at 11:59 p.m., all Murania Press books are on sale. Prices have been marked down between 20 and 25 percent, and as always shipping is included for domestic U.S. customers.

What’s different about this sale is that it will be the last one for certain titles in our catalog. I’ve recently been informed by our printer that costs are going up for the first time in nine years. Rather than pay more for books that are marginal sellers I will retire them from the line. So this will be your last opportunity to get some of these books.

PulpFest 2018 Report: Part Two

(All photos accompanying this report were taken by Curt Phillips unless otherwise noted.)

Any hopes I had for getting plenty of sleep on Friday were dashed quickly, as I spent most of the night tossing and turning. I mention this only because it affected my actions late Saturday evening, as you’ll see below.

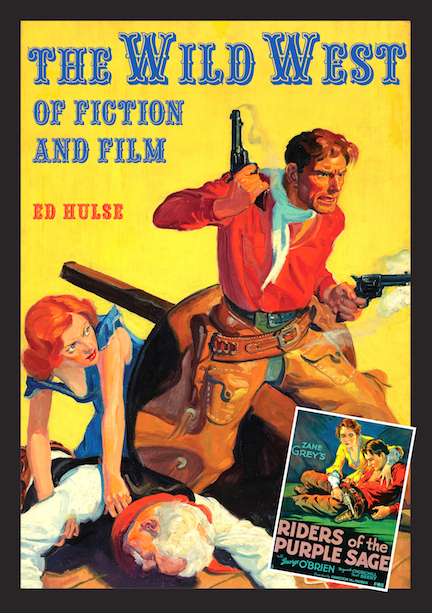

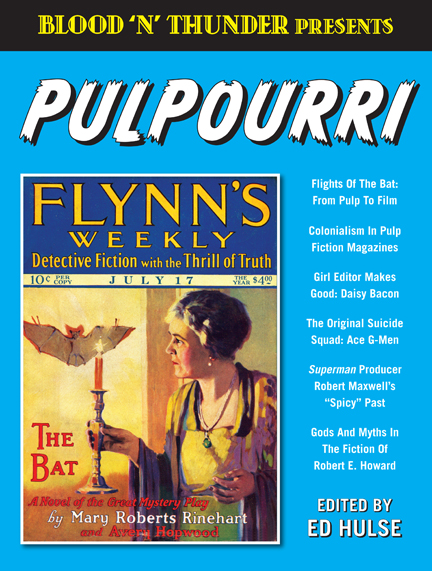

After breakfasting with pals I returned to the hucksters room for another day of wheeling and dealing. Sales of Murania Press product picked up, and by mid-afternoon I’d sold all available copies of our two most recent books, Blood ‘n’ Thunder Presents #4 and The Wild West of Fiction and Film. I also moved some of the collectable pulps and books on my table. Comics legend and old friend Jim Steranko stopped by for a lengthy chat, as did various PulpFest regulars I’d not yet had a chance to jawbone with. Periodic forays to tables manned by other dealers resulted in many purchases, some of them real bargains.

FarmerCon presentations and New Pulp readings (by Jim Beard, John Bruening, Win Scott Eckert, and Frank Schildiner) ate up the afternoon programming slots, and the day flew by rapidly. PulpFest held its usual Saturday-night dinner in the hotel, although for my evening meal I joined a large group that sauntered down the road to a local restaurant.

We were careful to finish eating in time for the annual business meeting, at which PulpFest committee members Mike Chomko, Jack Cullers, Barry Traylor, and Chuck Welch assembled on the dais to face convention attendees. It was an unexpectedly dramatic session owing to Jack’s revelation that the committee—burned out after years of mounting the con—would be losing Chuck, who is moving with his family to Canada. This loss promised to further burden the already-overworked committee members. Jack then dropped a bombshell: PulpFest has received an offer to merge with a larger comic convention back in Columbus, our original home. Nothing has been decided but the committee is carefully weighing all options. The ensuing discussion was lively but brief due to time constraints.

The business meeting drew a good-sized crowd.

Following the business meeting David Saunders, son of famed pulp artist Norman Saunders and designer of the Munsey Award for distinguished service to the pulp-collecting community, bestowed this year’s award upon William Lampkin, editor of The Pulpster, which doubles as program book and annual magazine. Mike Chomko accepted for Bill—a well-deserved honor, in my view—and read a brief statement.

Tony Davis, long-time former editor of The Pulpster, interviewed the convention’s Special Guest, author Joe R. Lansdale, whose multi-media credits are too numerous to mention here. That discussion was followed by a David Saunders presentation on the art of war pulps and a panel discussing WWI themes in the work of Philip José Farmer, featuring Christopher Paul Carey, Win Scott Eckert, and Paul Spiteri.

Although it’s embarrassing to admit, I skipped most of the Saturday-night programming out of fear I’d fall asleep and start snoring. Instead I mosied out to the Double Tree’s copious lobby and engaged in several lengthy conversations with various friends I’d not spent time with earlier.

Tony Davis (right) introduces Joe Lansdale.

The Saturday-night auction, another 200-plus-lot affair that promised to drag on for hours, got underway more or less on schedule shortly after 10 p.m. The Friday-night sale had been dominated by 12-issue lots of Wild West Weekly; Saturday night’s boasted similarly numerous batches of Western Story Magazine. But there were other interesting items as well, and I had my eye on one in particular: the 1941 issue of Thrilling Adventures that introduced Thunder Jim Wade in a novel credited to Charles Stoddard but actually written by prolific SF author Henry Kuttner. It came up late in the auction, when I was fighting to stay awake.

I didn’t have much competition for the pulp and won it for a reasonable price. Bleary-eyed and somewhat dazed (more so than usual, that is), I shuffled up to the dais to pay for my item. You won two lots, I was told. No, I replied, just the one. Turns out I also won a pulp I couldn’t remember bidding on. That’s what acute sleep deprivation will do to you. After seeing the second item, a high-grade 1945 issue of Jungle Stories, I realized it was indeed something I would have competed for. Luckily, it had only cost me $30. In my zombified state I might have bid considerably more.

At this point I should’ve called it a day and gone straight to my room, but upon passing through the lobby I spotted a large group in conversation. As they were all friends, I pulled up a chair and gabbed with them until the gathering broke up sometime around 2 a.m.

Fortunately, I got just enough sleep to be coherent the next day. PulpFest’s Sunday session is always a short one; no programming is scheduled and dealers begin packing up at noon, even though the convention technically ends at 2 p.m. The worst part is saying goodbye to friends and fellow collectors I only see once or twice a year. The weekend always passes way too fast.

Inscribing a book at my table. Photo by Scott Cranford.

We were back on the road by 12:30 and reached my place in northern New Jersey some seven and a half hours later, at which time the Great White Whale disgorged a tired but satisfied quintet of pulp fans.

So how did this year’s Pulpfest stack up against previous editions? On balance, quite well. It’s true that attendance was down and that dealer-room sales were not quite as robust as we would have liked. That speaks to an ongoing problem which deserves a separate discussion I might undertake here in a future post. Certainly the committee’s work was first-rate; Jack, Mike, Chuck, Barry, and their family members came through once again. I couldn’t detect any problems with the running of the show, although not having attended all the events I don’t know if any started egregiously late or were bedeviled by technical problems. PulpFest’s justifiably celebrated programming reflected the same careful thought and enthusiastic participation we’ve all come to expect.

In the end, we all have to wonder if this admittedly small, specialized hobby is large enough and strong enough to sustain two national conventions. The first PulpFest, back in 2009, nearly tripled the attendance at the disastrous 2008 Pulpcon, which killed off that venerable confab. The second and third saw additional growth, but subsequent years—when we moved to downtown Columbus—found the show leveling off. The 2017 move to this current location was widely heralded for the excellence of the venue, but PulpFest has not had noticeable support from fans in Pittsburgh and the surrounding communities. Hence the decline in attendance.

I don’t know what the answer is. I don’t know that there is an answer. But like I said above, the issue needs to be addressed. In the meantime, let’s all wish the PulpFest committee members well as they grapple with the tough decisions that lay ahead.

PulpFest 2018 Report: Part One

(All photos accompanying this report were taken by Curt Phillips unless otherwise noted.)

Last Thursday morning my New Jersey home was the site of a rendezvous with fellow pulp aficionados Nick Certo, Scott Hartshorn, Digges La Touche, and Walker Martin. They arrived shortly before 9 a.m. for our annual trip to PulpFest. We’ve been traveling together for many years now (the same motley crew accompanies me on our trip to the Windy City pulp convention every April), always riding in a rented 15-seat van we’ve affectionately dubbed the Great White Whale. There might only be five of us, but we need a vehicle that big to hold our dealer stock and convention purchases, so the rental agency removes the last two rows of seats for us.

We loaded up in double time and made a quick stop for coffee at my local Dunkin Donuts, as per our usual custom. By 9:30 we were zooming westward on Route 80, once more bound for the Double Tree Hilton Pittsburgh—Cranberry, which despite its name is actually located in Mars, Pennsylvania. Last year’s PulpFest was the first staged in this excellent venue, and we all looked forward to returning.

Arriving just before 5 p.m., we unloaded luggage and stock and made a beeline for the 13,500-square-foot ballroom that doubles as the con’s exhibit space. I dumped my boxes on the table assigned to me but didn’t bother setting up, preferring to canvas the room for bargains.

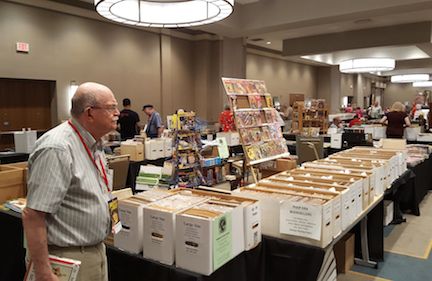

Long-time collector Walter Albert scans the dealer room.

Almost immediately I spotted an eye-popping display of high-grade, dust-jacketed editions of Chelsea House books reprinting stories from early Street & Smith pulps. Dozens and dozens of them. For more than 15 years I’d been seeking a copy of Cherry Wilson’s Stormy, originally serialized in Western Story Magazine. And there it was, right in front of me! I snatched up the book only to be informed by dealer Scott Edwards that fellow dealer and uber-collector Rich Meli had just that second purchased the entire lot. I was crushed. But at a table just down the aisle from Scott’s exhibit, my long-time friend Sheila Vanderbeek had just laid out another batch of Chelsea House first editions. Lo and behold, she too had a copy of Stormy! It lacked the wrapper and wasn’t quite as sharp as Scott’s, but I grabbed it nonetheless. My long search was over. O frabjous day!

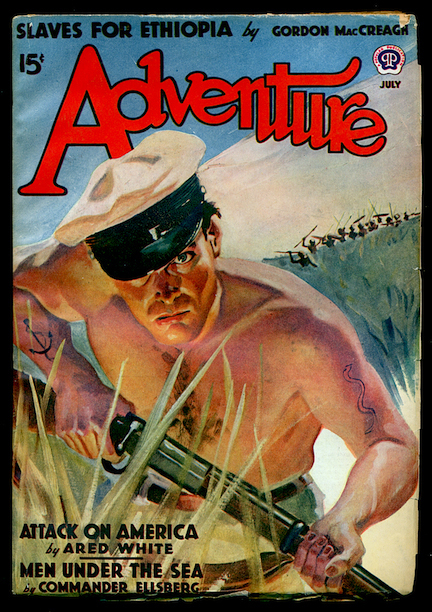

I joined a bunch of friends and fellow attendees for dinner, which took longer than anticipated and caused us to miss the show’s first programmed event. This year’s PulpFest celebrated the 100th anniversary of World War I’s conclusion, with the Philip José Farmer centennial a sub-theme being explored at Farmercon, PulpFest’s satellite gathering. Sai Shankar, whose Pulp Flakes blog is a treasure, discussed the life and output of Leonard Nason, a treasured contributor to Adventure who specialized in stories about the Great War. Sai’s presentation was followed by one from Burroughs Bulletin editor Henry Franke covering the War’s impact on ERB’s work. Michelle Nolan brought up the rear with an exploration of war comics. Fairly exhausted from my preparations for the trip and the long drive I retired early and was sound asleep by midnight. But I woke up at about 1:30 and couldn’t get back to sleep.

Friday’s session opened promisingly as bargain seekers hurried from table to table, but within a few hours the pace slowed and it occurred to me attendance might be down somewhat. (Later on, PulpFest chairman Jack Cullers confirmed that to me.) Quite unintentionally, pulp-convention huckster rooms often have their own theme—being dominated one year by hero pulps, the next by detective pulps, and so on—and this time around PulpFest was surfeited with Westerns. The two auctions, being made up primarily of material from three estates, fairly teemed with them. I had quite a few in my 20-percent-off Bargain Box. And even dealers who normally don’t stock the things, like Connecticut’s Paul Herman, were offering them in large quantities.

Dennis Harford making a box-by-box search for treasure.

Afternoon programming mostly featured readings from New Pulp authors, per usual. I heard good things about Christopher Paul Carey’s recitation from Swords Against the Moon Men, his authorized sequel to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Moon Maid. (Artist Mark Wheatley was also on hand to display his gorgeous illustrations for the book.) Chris and Mark, joined by Mike Croteau and PulpFest Special Guest Joe Lansdale, discussed the influence and legacy of Philip José Farmer in one of the prime-time sessions. That was followed by a presentation by Bob Deis and Wyatt Doyle on war-themed material in men’s “sweat” magazines. Next was a panel on air-war pulps featuring pulp historian Don Hutchison, PulpFest’s own Mike Chomko, and Age of Aces principals Bill Mann and Chris Kalb. After that Bob Gould, son of prolific Popular Publications illustrator John Fleming Gould, entertained con attendees with an account of his dad’s career.

Auctioneers Joe Saines (left) and John Gunnison.

The Friday-night auction featured a variety of items but was dominated by heavy bidding on nearly innumerable 12-issue lots of Street & Smith’s long-running Wild West Weekly. I didn’t compete for most of them—wouldn’t bid against good friends who had already expressed interest—but managed to win a dozen from 1936 and a dozen from 1943, the magazine’s last year. One lot set me back $50, the other $45, for a per-issue cost of four dollars. Not bad. Regular PulpFest auctioneers John Gunnison and Joe Saines did their usual top-notch job keeping things moving and disposing of more than 200 lots in record time. Even so, it was past 1 a.m. when they brought the gavel down on the last, and having gotten less than two hours of sleep the previous night I staggered back to my room for what I hoped would be deep, lengthy slumber.

(Part Two will follow shortly.)

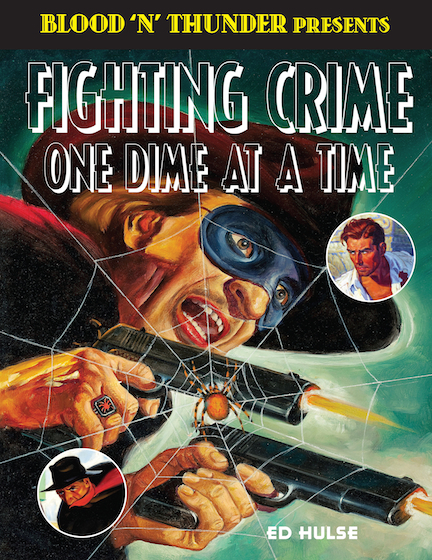

The Latest from Murania Press

Our newest release is The Wild West of Fiction and Film, a 286-page, 146,000-word tome that concentrates on the nexus of American popular fiction (especially pulp) and Western movies produced during Hollywood’s Golden Age. It contains 16 essays, some of which first appeared in issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder, some in other publications, and one written just for this book. That piece extensively covers the 1932 George O’Brien vehicle Mystery Ranch, a classic exercise in Western Gothic adapted from Stewart Edward White’s 1919 novella “The Killer,” which is reprinted in its entirety. The other 15 essays have been revised and reedited, with significant wordage added in some cases. Accompanying them are two 20-page picture galleries featuring rare pulp covers and a mix of original stills, posters, lobby cards, and advertisements for the individual films under discussion.

To be honest, we compiled The Wild West of Fiction and Film for genre devotees not especially interested in pulp history, but in our opinion the book features a good balance between coverage of rough-paper magazine stories and their celluloid adaptations. And, of course, it’s always nice to have so much thematically linked material in one volume for handy reference. You can check out The Wild West here.

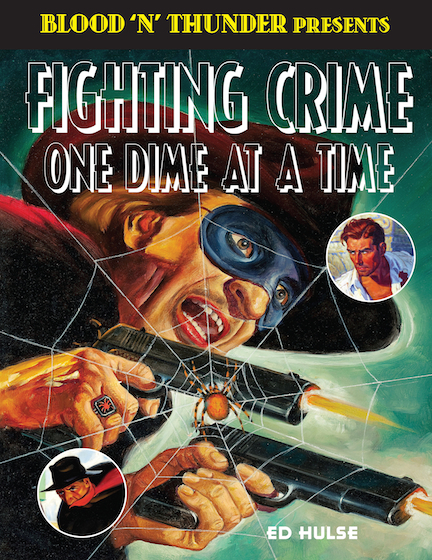

While you’re at it, by all means take a look at the listing for Pulpourri, the fourth volume in our Blood ‘n’ Thunder Presents series. Released last month, this 220-page book collects nine meaty essays along with a photo feature and two pulp-story reprints. With one exception (“Mates for the Morgue Master,” a 1939 Arthur J. Burks weird-menace story) none of this material previously appeared in BnT. And the Burks yarn dates all the way back to our second issue, published in Fall 2002. So it’s practically new.

For more information on Pulpourri, check out the listing here.

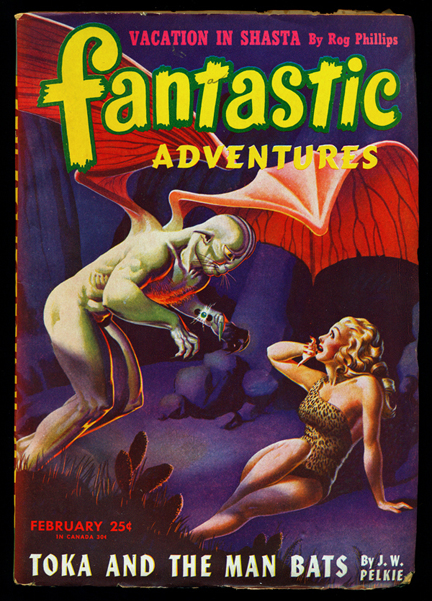

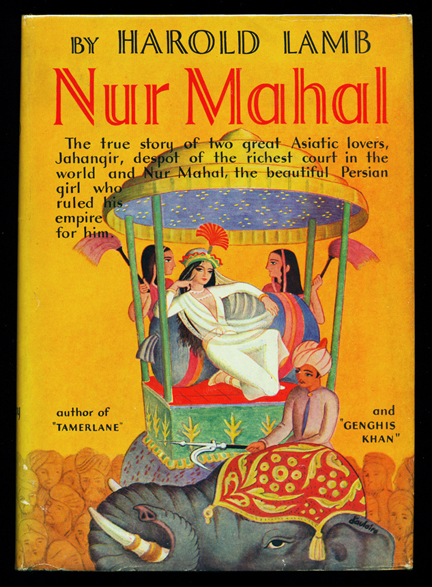

June 2018 Collectibles Section Update

It’s been a while since our Collectibles for Sale section was last updated, so we’ve just freshened it up with a couple dozen new items: pulps, pulp reprints, and pulp-related books. As usual, there’s a nice assortment of high-grade items, including some unread copies in As New condition. There are also a few bonafide rarities, including a beautiful first edition of Harold Lamb’s historical novel Nur Mahal inscribed by the author. Signed copies of books by this Adventure and Argosy favorite seldom turn up, especially in good shape. Also listed is the nicest copy we can remember seeing of Five Sinister Characters, a 1945 Avon pulp digest that reprinted for the first time a quintet of Raymond Chandler stories originally published in Dime Detective. It’s a fairly common item, but not in Fine condition with nice paper.

There’s a nice variety of material in the two dozen new items. Check ’em out. Below are a few samples….

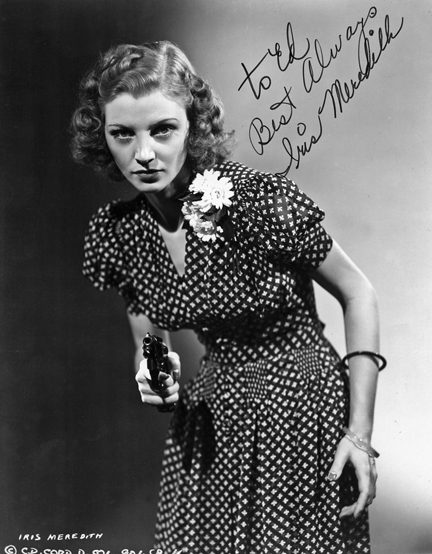

Happy Birthday, Iris Meredith!

Back for another go-round is one of the most popular and frequently commented-upon articles in Blood ‘n’ Thunder history: “My Dinner with Nita,” a tribute to Iris Meredith, the lovely actress who played pulp-fiction heroine Nita Van Sloan in a 1938 Columbia serial, The Spider’s Web. It first ran in issue #15 (Summer 2006) and was later reprinted in Blood ‘n’ Thunder’s Cliffhanger Classics. Several years ago it appeared as an interstitial piece in one of Sanctum Books’ Spider pulp-reprint volumes. Since Iris would have turned 103 today, I’m giving the piece another airing. Below you’ll find the complete text of “My Dinner with Nita.” I hope you enjoy it….

In the summer of 1976, I had an experience most serial fans could only dream of. I actually met, interviewed, and broke bread with the Spider’s paramour, Nita Van Sloan!

Not the real Nita, of course. That would have been impossible, because there wasn’t any real Nita. No, I attended a dinner with the reel Nita, the beautiful actress who played opposite Warren Hull in The Spider’s Web (1938), first of two fast-action Spider chapter plays made and released by Columbia Pictures.

Her name was Iris Meredith, and she had come to Nashville, Tennessee as a guest of the Fifth Annual Western Film Fair, a movie-buff confab sponsored by Western Film Collector magazine. Over the course of this four-day convention, some 160 feature-length films and a couple dozen serials—among them The Spider’s Web—unspooled in six makeshift screening rooms outfitted with 16mm projectors manned by bleary-eyed collectors. Movie showings began at 10 a.m. every day and continued until the wee hours of the next morning. The hucksters’ room included well over a hundred tables, some of them covered with boxes of vintage-movie memorabilia, others sagging beneath the weight of film cans containing 16mm prints. Film Fair attendees could screen themselves blind or spend themselves poor. Some, like me, did both.

Much-needed diversions were provided by panel discussions (in which the many guest stars reminisced about filmmaking in the Good Old Days) and the Saturday-night awards banquet, when actors long forgotten by the public at large accepted handsome plaques and standing ovations from True Believers who still cherished the Saturday-matinee movies of their youth.

I had already attended several such events and would likely have returned to Nashville even if Iris Meredith hadn’t been among the dozen or so performers invited to this year’s convention. But her presence was the icing on the cake for me. To think I’d be meeting the silver screen’s one true Nita Van Sloan! (Those of us who had seen both Spider serials rarely spoke of The Other, that brassy, garish floozy so obviously miscast in the 1941 sequel, The Spider Returns. As far as we were concerned, Iris Meredith was Nita. Period.)

Born on June 3, 1915 in Sioux City, Iowa, Iris Shunn didn’t have an easy childhood. By the time she was 10 her family had moved twice, first to Minnesota and then to southern California. By the time she was 13 both parents had died, leaving her to support three younger siblings with a Depression on the way. She attended school in the morning and toiled as a theater cashier in the afternoon and evening. Legend has it Iris was discovered by a talent scout while working at the Loew’s theater in downtown Los Angeles. Still just a teenager—albeit a beautiful one—she briefly joined the fabled Goldwyn Girls and first appeared on screen with them in a 1933 Eddie Cantor vehicle, Roman Scandals.

Iris worked as a chorus girl in several movie musicals before landing her first substantial part: an ingénue role in The Cowboy Star (1936), a better-than-average “B” Western in which she played opposite Charles Starrett for the first time. (This film was the first in which she received on-screen billing, and for it she assumed the Meredith surname.) Starrett, scion of a wealthy northeastern family, had taken up acting while attending Dartmouth College. He never really caught on with adult moviegoers and in 1935 began starring in low-budget horse operas released by Columbia. He spent 17 consecutive years making Westerns for that studio, appearing exclusively as The Durango Kid from 1945 to 1952.

When Iris landed a Columbia contract, she was initially assigned to the unit cranking out Charlie’s pictures, and she co-starred with him in some 19 Westerns released between 1937 and 1940. The Starrett vehicles of this period maintained a fairly high standard, but their strict adherence to formula made one virtually indistinguishable from another. The Sons of the Pioneers, a Western-music group to which Roy Rogers once belonged, worked with Charlie and Iris in every picture. The supporting casts nearly always included Dick Curtis as the principal heavy and silent-screen veteran Edward Le Saint as either Starrett’s or Meredith’s father. Even the bit players were the same from picture to picture, and they almost always wore the same clothes. For that matter, so did Iris: She generally showed up in an ensemble consisting of plaid shirt with vest and split skirt.

Iris lobbied for parts in better movies but rarely escaped confinement in the Western and serial unit headed by producer Jack Fier. When she did, it was only temporarily and usually in a thankless role. In late 1940, after appearing in 22 Westerns and three serials, she left Columbia. For the next couple years Iris freelanced, finding it difficult to land roles outside of Hollywood’s Poverty Row. By 1943 she had married director Abby Berlin, himself a Columbia contractee; shortly thereafter she had a daughter and settled into domestic life.

Unlike some of her contemporaries, Iris never attempted a comeback when television series production created new opportunities for technicians and performers used to working at top speed on short budgets. She never dreamed that people still remembered her fondly, or that she had won new fans thanks to TV reruns of her old movies and the proliferation of 16mm dupe prints of the old Westerns. By the mid Seventies, however, word had gotten out. The “B”-Western stars, starlets, and supporting players were very much in demand at nostalgia-oriented film festivals, and Iris eventually accepted an invitation to appear at one such event.

Of course, those of us who attended that 1976 Western Film Fair had no way of knowing what hell Iris Meredith had been through. Some ten years earlier she had been diagnosed with oral cancer. She endured 14 operations, ultimately surrendering part of jaw and tongue in her fight against the disease. None of us expects our film favorites to withstand indefinitely the ravages of time, but we weren’t fully prepared for the severely disfigured, prematurely aged woman who courageously greeted her fans.

However shocked Film Fair attendees may have been, they never let on. Iris bravely met and talked with all of us, laboring mightily to make herself understood. Losing part of her tongue made it impossible to clearly articulate certain words, and her slurred speech was reminiscent of someone who’d had way too much to drink.

But this didn’t matter to us, and our outpouring of love plainly lifted her spirits. As the convention progressed Iris seemed demonstrably happier; by the second or third day one could see a twinkle in her rheumy eyes. Initially reluctant to speak, she pushed herself to engage fully with fans who approached her with questions as well as stills and lobby cards for her to sign.

She was accompanied by her grown daughter, who occasionally sat with her mom when Iris elected to watch one of her old movies. About halfway through a screening of The Spider’s Web—all 15 chapters in one marathon session, interrupted only by the projectionist’s reel changes—the daughter excused herself, leaving Iris alone. The screening rooms were sparsely attended at that moment; my recollection is that another guest-star panel was just getting underway. Only a dozen or so people remained to see the Spider battle his arch-foe, the Octopus, to a standstill.

A few rows behind and to the right of Iris, I stared at the erstwhile actress as the next episode began. She sat very still and straight, apparently transfixed by the flickering image of a younger, beautiful version of herself. I couldn’t help but wonder what might be going through her mind. Having already seen the serial several times, I left after one more chapter to attend another screening. As I eased through the screening-room door I shot a glance back at her. She was still riveted by the adventures of Dick, Nita, and the others.

On the third day of the convention, I persuaded Iris to sit for an interview. We adjourned to a small meeting room down the hall from the massive ballroom that housed dealers and other stars. She briefly stiffened when I brought out my portable cassette recorder, but after a few seconds—just as I was about to stuff it back into my briefcase—she relaxed again. “What would you like to know?” she asked.

Naturally, I was most eager to hear whatever she had to say about The Spider’s Web. “You know,” she said, “a year ago I couldn’t have told you anything about it. But now that I’ve seen it again, little things come back to me.

“Those serials were very hard to do. With the Westerns, you worked for a week or two and then you had time off. But those damn serials went for four, or five, or six weeks at a time. And we worked very long days, sometimes 12 or 14 hours. So every night you came home exhausted. It was all we could do to remember our lines the next day. The directors had it bad because they had to keep track of everything, all those little things that happened in the chapters.”

I asked her what she remembered about her castmates.

“Well, of course, I knew Richard Fiske already. We worked together on some of the pictures I did with Charlie [Starrett]. Warren Hull was a dear. Between takes he was a great kidder. And he loved to sing. He had a lovely voice. But then we would get in front of the camera and he would get so serious and squint, you know, and start shooting at people.

“I remember we all thought it was funny that Kenny Duncan was playing this Hindu [Ram Singh]. He was Canadian! And they gave him some of the craziest lines to say.” (I imagined Iris was referring to Ram Singh’s snarling threats, like my favorite: “Dog with a pig’s face! If I had my knife, I’d carve my name in your heart!”)

“The other thing I enjoyed was that I got to wear nice clothes. I only had a few changes of wardrobe, but it was so much fun to wear nice dresses after doing all those Westerns in that damn split skirt. And of course, in the Spider film I didn’t have to deal with horses.”

Iris insisted, as had so many serial actors before and since, that she barely remembered making the chapter plays. “Really, we were rushing around so much we didn’t know half the time whether we were coming or going. The scripts were as thick as telephone books and every night I only memorized as many lines as I needed for the next day. We didn’t shoot the chapters separately, it was all done according to where on the back lot we were scheduled to be on any given day. Or on which set; we did many scenes on sets that had been built for other movies. I still wonder how the production managers kept things straight [during the making of a serial].”

She did, however, have specific memories of Overland with Kit Carson, the 1939 serial she did with newly minted cowboy star “Wild Bill” Elliott. “We went to Utah to shoot most of it,” she told me. Then she tried to pronounce the name of the town where the company stayed while on location, but I couldn’t understand what she was trying to say. Finally she scribbled the name on my note pad: “Kanab.” Several Westerns were made in and around that community, which the town fathers hoped would attract Hollywood producers in greater numbers. A Western street was built in the area to make Kanab a more appealing location for filmmakers; Overland with Kit Carson was the first production to utilize it.

Iris was fond of her Kit Carson co-star, with whom she also made three feature films. “Bill Elliott took his work very seriously,” she said. “The first picture I made with him, he wasn’t much of a rider yet. But he always practiced between takes. He got to be very good at it. And you know how he wore his guns, backward in the holsters? Well, he spent hours practicing a quick draw with those guns. I really admired him for working so hard to be convincing.”

She also had kind words for Ed Le Saint, another member of the Starrett stock company. “He was such a dear man. Very kind to me. But, you know, he was so old! I could never understand why they cast such an old man to play my father. Really, he was old enough to be my grandfather.”

By this time Iris seemed to be enjoying herself. She was no longer self conscious about the tape recorder, or about the effort it took to pronounce certain words. But I inadvertently brought our chat to an awkward halt with my next question:

“In 1940 you did your last serial, The Green Archer, for one of your Spider’s Web directors, James W. Horne. What do you remember about that film?”

Her face clouded and the spark went out of her eyes. She seemed more than a little sad as she quietly replied: “I don’t want to talk about that film. Please don’t ask me about it.”

I was stunned. What on earth could have happened during the making of that serial to elicit such a reaction? Fortunately, Green Archer was the last film about which I’d wanted to ask, and with nothing else to say I cleared my throat nervously and mumbled, “Well, I think we’ve pretty much covered everything.” I thanked her, she thanked me, and as I got up from the table I could see several dozen fans milling outside in the hall, waiting for a chance to say hello and get her autograph.

That night at the banquet, following the typical rubber-chicken dinner, Iris Meredith was one of a dozen people presented with the inscribed plaque traditionally given to Western Film Fair guest stars. As she made her way to the podium, every person in the ballroom rose to give her a lengthy standing ovation. It was our way of honoring her for the courage and grace she had exhibited during the show. The room fairly crackled with electricity. Even from where I was, some ten feet from the dais, I could see her eyes welling up with tears. When the applause died down, she said just two words: “Thank you.” Then, as it swelled again, she took her seat and stared intently at the plaque, as if embarrassed to make eye contact with her adoring fans.

Subsequently Iris Meredith attended another film festival, but she never became a regular on the “nostalgia circuit” as did some of her contemporaries. She continued her brave struggle with cancer, but the disease eventually overtook her. Not yet 65 years old, Iris died on January 22, 1980.

In 40 years of convention-going, I’ve met dozens of the actors, writers, directors, and stuntmen who worked on my favorite serials, Westerns, and “B” movies. I’ve enjoyed my encounters with all but two or three of them. But none ever affected me quite the way Iris Meredith did. It’s difficult to explain, but even now, decades later, I get a little thrill whenever I revisit The Spider’s Web and behold each chapter’s optical player credits—you know, those glimpses of the principal actors with their names splashed across the bottom of the frame. Iris always stands there, clad in Nita Van Sloan’s flying togs, smiling sweetly and placidly even though she will shortly find herself menaced yet again by minions of the Octopus.

In those brief moments, I like to pretend she’s smiling at me.

2018 Windy City Film Program

As always, this year’s Windy City Pulp and Paperback Convention film program boasts a number of obscure motion pictures adapted from pulp stories. There’s often an exception, though, and this year it’s The Keep (1983), based on the novel by special guest F. Paul Wilson, who will be on hand for the screening. Also as always, the film program is sponsored, assembled, and presented by Murania Press and Blood ’n’ Thunder. If you plan on attending the convention, here’s what you can expect. If not, here’s what you’ll be missing….

FRIDAY

12 p.m. — They Came from Beyond Space (1967).

Adapted from “The Gods Hate Kansas” (Startling Stories, November 1941) by Joseph Millard.

This British-made SF offering is decidedly cheesy but pleasantly old-fashioned in its approach. An Amicus production written by the company’s co-founder, Milton Subotsky, and directed by genre specialist Freddie Francis (who worked simultaneously on horror/SF films for Amicus and Hammer), They Came from Beyond Space takes place in rural England. Scientists descend upon a farm field to investigate a shower of small meteorites that landed in a V formation, suggesting an intelligent design. American actor Robert Hutton, a once-promising performer who landed a contract with Warner Brothers but failed to catch fire with the public and drifted into TV during the Fifties, stars as Dr. Curtis Temple, forbidden from joining his colleagues because he’s still recovering from injuries sustained in a car accident. Just as well: the investigating scientists, including Temple’s girlfriend Lee Mason (Jennifer Jayne), are possessed by an alien life force and turned into robotic slaves working upon behalf of the extraterrestrials. He finally goes to the remote camp but seems immune to whatever it is that now controls Lee and their co-workers. Why? And can he use this immunity to rescue his friends?

Those are the burning questions ultimately answered by director Francis and company in 85 minutes of low-budget foolishness. They Came from Beyond Space is a minor and curious addition to the roster of films adapted from pulp stories; we can’t honestly say you’d be missing a forgotten gem if you choose to pass it up and spend the convention’s first hour and a half in the dealer’s room. But it has a measure of charm, to be sure, and if you look carefully among the supporting players you’ll see Michael Gough, whose later screen accomplishments included playing Alfred the butler in the Batman movies starring Michael Keaton.

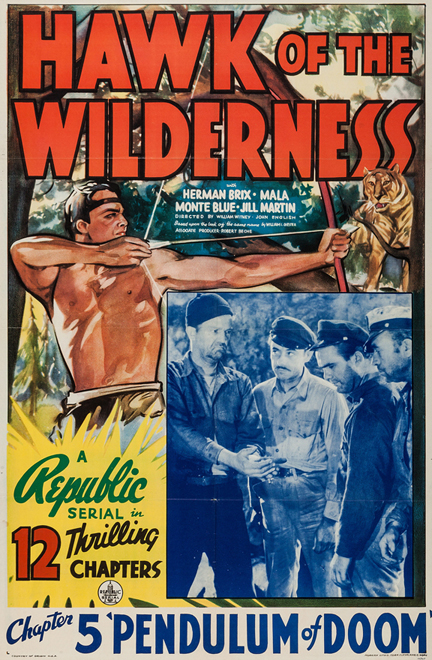

1:30 p.m. — Hawk of the Wilderness (1938).

Adapted from “Hawk of the Wilderness” (Blue Book, April-October 1935) by William L. Chester.

Of all the imitation Tarzans who paraded through pulp pages in the wake of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ immortal ape man, William L. Chester’s Kioga the Snow Hawk was possibly the best. Chester came from out of nowhere, with no previous fiction-writing credits, and sent his first novel, Hawk of the Wilderness, to Blue Book editor Donald Kennicott. It was accepted with alacrity, serialized during 1935, and published in hard covers by Harper & Brothers the next year. Chester wrote three sequels for Blue Book, which serialized one a year for 1936, 1937, and 1938. After selling an isolated short to Adventure, he apparently gave up writing fiction—and the pulp world lost a talented storyteller.

Republic Pictures licensed the first Kioga yarn upon its publication by Harper in 1936. Chester’s novel was entrusted to the serial unit for adaptation. For reasons unknown, however, a workable script wasn’t completed until 1938. The studio then cast Herman Brix, an Olympic athlete and former screen Tarzan, as the Snow Hawk; he had previously taken prominent roles in two other 1938 chapter plays for Republic, The Lone Ranger and The Fighting Devil Dogs. Both were directed by the formidable team of William Witney and John English, who had evolved a style of action filmmaking that would result in an unbroken string of successful serials regarded by aficionados of the form as among the best ever made.

Hawk of the Wilderness was shot in less than a month, with the dense forests near California’s Mammoth Lakes standing in for the uncharted volcanic island Chester placed in the Arctic Circle. As might have been expected, Republic’s screenwriters took liberties with the original work (such as elevating a minor character named Solerno to chief villain) but maintained fidelity to the basic concept. Brix was more than qualified to handle such daring physical feats as the script demanded, and he did his share of tree-swinging in Tarzan fashion. Hawk is a fine serial, beautifully photographed and loaded with action. It’s marred only by some unfortunate, stereotypical “comedy relief” from an African-American actor billed as “Snowflake.”

3:30 p.m. — The Keep (1983).

Adapted from the novel by F. Paul Wilson.

The Windy City film program occasionally deviates from its stated mission to offer only obscure movies adapted from stories that originally appeared in pulps. This year’s exception is being made in deference to our guest star, F. Paul Wilson, whose Repairman Jack novels are very much in the pulp tradition, being fast-action thrillers with supernatural underpinnings. The Keep, published in 1981, was his first horror story. Two years later it was brought to the screen by Michael Mann, who not only penned the adaptation but directed the film as well.

The story takes place during World War II, with Nazi soldiers and commandos being killed off in a mysterious castle in the Carpathian Mountains. It appears that some ancient demonic force within the fortress walls has been unleashed, and Nazi commander Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne) eventually—and ironically—calls upon an eminent Jewish scholar, Dr. Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellen), to identify and help defeat the malevolent entity. The presence of an enigmatic man named Glaeken (Scott Glenn) may have something to do with his problem.

Although The Keep was both a critical and commercial flop upon its theatrical release, but with subsequent exposure on TV and video the film has become a cult favorite in certain precincts. Wilson himself once described it as “visually intriguing, but otherwise utterly incomprehensible.” He’ll be on hand for our screening and is expected to make additional comments. Trust us, you’ll want to be there.

Immediately following evening auction — The Devil’s Saddle Legion (1937).

Adapted from “Hell’s Saddle Legion” (Big-Book Western, November-December 1936) by Ed Earl Repp.

The ninth of Dick Foran’s 12 “B” Westerns for Warner Brothers is a pretty fair horse opera, not as good as some of his earlier ones but certainly better than the three to come. Produced for approximately $64,000—a meager outlay for a major studio, even in those Depression days—The Devil’s Saddle Legion returned $158,000 in film rental (the fees paid by exhibitors). With studio overhead, distribution costs, and advertising and promotional expenses subtracted, it returned a tidy $34,500 net profit to Warners. That doesn’t sound like much in today’s world of billion-dollar blockbusters, but those “B”-picture profits made up for a lot of many rarified “A” movies that lost money.

During the 1880s, the region bordered by the Red River is claimed by both Texas and the wild and woolly Oklahoma Territory. Tal Holloway (Foran) has just returned to Texas when he witnesses the murder of a family friend. Arrested by a crooked sheriff, Tal winds up in a prison camp whose inmates are providing slave labor for a big project: the building of a dam that would change the Red River’s course and allow corrupt Hub Ordley (Willard Parker) to claim additional land for Oklahoma. Can Tal escape from the camp and clear his name?

A burly redhead from New Jersey, Foran was also a baritone who signed with Warner Brothers just as a young upstart named Gene Autry was commencing his series of musical Westerns for Republic Pictures. Warner’s “B”-picture production head Bryan Foy had writers hastily retool their script for an oater called Boss of the Bar-B Ranch, inserting several songs and retitling it Moonlight on the Prairie. Thus Dick Foran, a most unlikely Western star, became the screen’s second singing cowboy. He occasionally appeared in Warner “A” pictures, most notably The Petrified Forest (1936), but he never attained real stardom and eventually drifted to other studios after his Warner Brothers contract expired, always mired in low-budget fare. But he maintained a high average in these little sagebrush sagas, and The Devil’s Saddle Legion is quite entertaining.

SATURDAY

10 a.m. — The Ice Flood (1926)

Adapted from “The Brute Breaker” (All-Story Weekly, August 10, 1918) by Johnston McCulley.

Zorro’s creator was a prolific contributor to the Munsey pulp chain long before he wrote “The Curse of Capistrano” for All-Story Weekly; he placed stories with The Argosy back in 1907 and within five years was selling to The Cavalier, The Scrap Book, and The Railroad Man’s Magazine. (His byline could also be seen regularly in pulps published by other companies, including Blue Book, Top-Notch, and Adventure.) But it was the success of “Capistrano,” licensed for the screen by Douglas Fairbanks and released as The Mark of Zorro, that brought his other work to the attention of Hollywood. Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures did not often purchase screen rights to pulp-magazine stories, but the company bought McCulley’s “The Brute Breaker” sometime in the early Twenties only to sit on it for several years. When produced in 1926

Recent Oxford graduate Jack De Quincy (Kenneth Harlan), scion of a lumber magnate, is dispatched by his father to the northwest to “clean up” a few camps whose output is falling due to raucous behavior, insufficient discipline, and ineffectual management. Working undercover, without any outside help, Jack uses his fists as well as his brains to establish a reputation as a wildcat. He manages to run afoul of pretty Marie O’Neill (Viola Dana), a superintendent’s daughter, but also identifies two bullies as bootleggers operating their racket from one of the camps.

A vigorous action melodrama that climaxes with Jack’s rescue of Marie from gathering ice floes on the frozen river, The Ice Flood turned out much better than anyone at Universal anticipated. Possibly the muscular direction of George B. Seitz, a no-nonsense helmer whose experience dated back to Pearl White serials of the Teens, had much to do with the picture’s reaction. Laemmle insisted the picture be released as a “Universal Jewel,” a designation usually reserved for the company’s biggest productions. Critics were somewhat less impressed, and the picture did only modest business. But it’s a fine film of its type, very much the type of movie we enjoy introducing to pulp fans here at Windy City.

11:15 a.m. — The Flying Squad (1940).

Adapted from “The Flying Squad” (Detective Story Magazine, November 3-December 8, 1928) by Edgar Wallace.

The staggeringly prolific Wallace had already created the Four Just Men and Sanders of the River by the time he began selling thrillers to such American pulps as Flynn’s, The Popular Magazine, and Detective Story Magazine. The latter serialized no less than two dozen of his novels, beginning with Jack o’ Judgment in 1920. Th Flying Squad appeared in that long-running Street & Smith pulp prior to being issued in cloth by Doubleday as one of its Crime Club selections.

Scotland Yard Inspector Bradley (a young and handsome Sebastian Shaw, unmasked as the dying Darth Vader in Return of the Jedi) is slowly but surely closing in on a smuggling ring headed by suave Mark McGill (Jack Hawkins), who concocts a scheme to throw Bradley off his trail. Having murdered one of his henchmen, McGill tells the dead man’s sister, Ann Perryman (Phyllis Brooks), that Bradley was responsible for her brother’s death by shooting. In her grief, Ann allows herself to be drawn into McGill’s orbit out of a desire for revenge on Scotland Yard and Bradley in particular.

The Flying Squad was the last motion picture directed by Herbert Brenon, a veteran of nickelodeon-era filmmaking whose most famous works included A Daughter of the Gods (1916), Peter Pan (1925), A Kiss for Cinderella (1926), and Beau Geste (1926). Brenon seemed out of sorts in Hollywood once talking pictures became the rage, and relocated in England in 1934. His handling of The Flying Squad, which very much resembles a conventional American “B” picture, is smooth and assured. It marked a pleasant diversion for Phyllis Brooks, the only American cast member, then at liberty following several years as a Fox contract player. (Brooks today is remembered, if at all, as a longtime paramour of Cary Grant.) In a key supporting role is Ludwig Stossel, who later emigrated to America, settled in Hollywood, and finished out his career as the “Little Ole Wine Maker” in TV commercials. But it’s Basil Radford, best known as half of the Charters and Caldicott duo from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes and Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich, who nearly steals the show as a ham actor and petty crook pressed into service by Inspector Bradley.

12:30 p.m. — The Return of Casey Jones (1933).

Adapted from “The Return of Casey Jones” (Railroad Stories, April 1933) by John Patrick Johns.

This Poverty Row production was already underway when the story on which it was based appeared in Railroad Stories. In fact, a cover blurb alerted readers that a celluloid version of the John Patrick Johns short story would soon hit theater screens. We don’t know how or why this occurred; such things had happened before but were very rare. Johns was a specialist in this tiny sub-genre; he wrote exclusively for Railroad Stories and its later incarnation, Railroad Magazine.

Casey Jones, of course, was a real-life railroad engineer who in April 1900 sacrificed his own life to save passengers and other crew members. Knowing that his train was certain to crash into a stalled freight train on a Mississippi track, Casey remained in the cab, rather than jump off, in a successful bid to slow the locomotive. He was the only fatality, and his heroic deed became the stuff of legend. The Return of Casey Jones features Dartmouth football player and future cowboy star Charles Starrett as Jimmy Martin, an engineer wrongly pegged as a coward when he slips and falls from a train just before it hurtles over a precipice. He is thought to have jumped rather than attempt to slow the engine. He becomes a pariah, and his heartbroken girlfriend Nona (Ruth Hall) gives him up for a soldier, “Wild Willy” Bronson (George Walsh). The remainder of the story depicts Jimmy’s attempts to redeem himself.

Entertaining but hardly a world-beater, Return of Casey Jones is typical of the independently produced melodramas that emanated from Hollywood’s smaller studios during the Thirties and Forties. Starrett is a likable leading man, although Hall is such a pallid ingenue that any viewer could have forgiven Jimmy for thinking he was better off without her. Walsh, a silent-screen star originally cast as Ben-Hur in M-G-M’s 1925 classic blockbuster and the brother of director Raoul Walsh, is fine as Starrett’s romantic rival, and the supporting cast is studded with familiar players like Robert Elliott, Jackie Searl, and George Hayes (pre-“Gabby”).

1:45 p.m. — The Whispering Chorus (1918).

Adapted from “The Whispering Chorus” (All-Story Weekly, January 12-January 26, 1918).

Sheehan, a fecund fictioneer whose byline could be seen constantly during the Teens in the Munsey pulps, is undeservedly forgotten today. He worked in several genres and has several classic pieces of fantastic fiction to his credit, including The Copper Princess and The Abyss of Wonders. Screen rights to his novelette “We Are French” (All-Story Cavalier Weekly, August 8, 1914) were purchased by Universal, whose 1916 adaptation of the yarn, The Bugler of Algiers, was one of the most profitable feature films released by the company up to that time. Director Cecil B. DeMille loved Whispering Chorus and urged his partner, producer Jesse L. Lasky, to license it from Munsey. Then he assigned the lead role to Raymond Hatton, at that time one of his stock company but later best known as a Western sidekick.

Having embezzled a large sum of money from his firm, John Trimble (Hatton) decides to abandon his wife and mother. Temporarily hiding on an island off shore, he changes clothes with a corpse and sends the unidentifiable body toward the city waterfront, where it washes up and is believed to be Trimble. The consequences of that act motivate the remainder of the film.

A sober, downbeat drama that DeMille believed would earn him plaudits from all corners, The Whispering Chorus flopped at the nation’s box-offices. The disappointed director never again attempted to do a “message” picture, electing instead to produce films with broad audience appeal. But this is a quality motion picture that illustrates silent-era storytelling at its best and is more highly regarded today than it was upon initial release.

WHISPERING CHORUS: Raymond Hatton and Kathlyn Williams.

3:15 p.m. — Hawk of the Wilderness, Chapters 7-12

Immediately following evening auction — Hopalong Rides Again (1937).

Adapted from “Black Buttes” (Short Stories, November 10-December 25, 1922) by Clarence E. Mulford.

One of the very best Hopalong Cassidy films, this 13th entry in the long-running series actually adapts a non-Hoppy novel by Clarence E. Mulford. Black Buttes, serialized in Short Stories prior to hard-cover publication by Doubleday, has as its protagonist one Wyatt Duncan, whose ten-year search for the man who raped his sister is rewarded when he infiltrates a gang of rustlers headquartered in the forbidding Black Buttes, in which stolen cattle seem to disappear—as do any ranch hands foolish enough to enter this accursed area.

Hopalong Rides Again takes little from the source material but the location of the rustlers’ stomping grounds—the Black Buttes—and the name of the villain, Hepburn. The rest of the story is cut from the series’ familiar pattern, with two important exceptions. First, it gives Hoppy a romantic interest in mature but attractive Nora Blake (Nora Lane); second, it introduces a juvenile cast member in Billy King, a 12-year-old trick rider hired by producer Harry Sherman to give young viewers someone with whom to relate.

The supporting players are those who remain dearest to the hearts of most Hoppy fans: Russell Hayden as hot-headed Lucky Jenkins; George Hayes as grizzled, garrulous Windy Halliday; and silent-serial star William Duncan as rugged old Buck Peters, owner of the fabled Bar-20 ranch. What distinguishes Hopalong Rides Again—in addition to the sturdiness of its deceptively simple plot, the romantic byplay between William Boyd and Nora Lane, and the smoothness of Lesley Selander’s direction—is its inspired use of the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, California. This picturesque location, used by filmmakers in hundred of movies, is beautifully captured by cinematographer Russell Harlan.

Closing Days of Year-End Sale

As we wish our friends and customers a Happy New Year, we just want to remind Murania Press fans that you have only three more days to take advantage of our year-end sale. Until 11:59 p.m. on Sunday, December 31st, all our books are available at 20 percent off the usual list price. Come midnight and the New Year, prices will revert to their normal levels. And remember, the sale prices include shipping to domestic U.S. buyers.

Remember, too, that once 2017 draws to an end we will no longer offer back numbers of Blood ‘n’ Thunder on a single-issue basis. Beginning in January we’ll be selling them in omnibus volumes of three issues each. Each omnibus will be well over 300 pages in length and therefore carry a $29.95 price tag (which, if you think about it, is actually less than the cost of three issues purchased individually).

Finally, as you prepare to spend this year’s Christmas cash from Aunt Fanny, don’t overlook our Collectibles For Sale section, which still lists lots of goodies for discriminating collectors.

Murania Press 2017 Year-End Sale

Beginning today, December 22nd, Murania Press books are available for a limited time at a 20-percent discount. In other words, the books normally priced at $20.00 can be now had for $16.00, the $25.oo for $20.00, and so on. Shipping to domestic U.S. buyers is still included. But this sale lasts for ten days only and expires at 11:59 p.m. on December 31st. All titles will revert to their normal price on New Year’s Day, 2018. Prices have already been reduced in each book’s listing here on the site.

Please note that the sale discounts apply only to standalone books in the catalog and not to back issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder. And remember, BnT back issues will not be offered singly after December 31st. They will be reconfigured in Omnibus volumes that will contain three issues each and sell for $29.95. These will become available in early 2018. There are several reasons for the change in back-issue availability, the most important being that rising production and shipping costs no longer make it feasible for us to offer publications priced in the $10-12.50 range. We’re making an exception for the very popular Flickering Shadows, which henceforth will be available at $12.50.

This is a great opportunity to catch up on such well-received Murania Press books as The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Sampler, the first three volumes in the Blood ‘n’ Thunder Presents series, and of course our perennial best seller, The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction. Now you know how to spent that Christmas check from Grandma. Don’t miss out!

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net