EDitorial Comments

Birthday Boy: Elmo Lincoln

The first actor to play Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes in a motion picture was born on this day in 1889 in Rochester, Indiana. Otto Elmo Linkenheit was a burly youth when he left his middle-class home for California. He held several jobs (including one as a longshoreman, where his prodigious strength was a decided asset) before breaking into silent films as an actor. Initially billed as Lincoln Helt, he became a protégé of prominent director D. W. Griffith, who cast him in The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (1913). Elmo got progressively better roles from Griffith in the director’s classic feature films Judith of Bethulia (1914), The Birth of a Nation (1915), and Intolerance (1916). Reportedly, Griffith was the one who persuaded the Indiana native to make Elmo Lincoln his stage name.

Elmo worked steadily over the next several years, eventually becoming a leading man in Might and the Man (1917). He owed his casting as ERB’s immortal Ape Man to a fluke. Producer William Parsons had originally cast an actor named Winslow Wilson to play the title role in his film adaptation of Tarzan of the Apes, which went before the cameras in the summer of 1917. At that time an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve, Wilson was called to active duty a few weeks after production began. Parsons was forced to suspend principal photography and resume casting in Los Angeles. Elmo’s massive physique and substantial acting experience made him the obvious choice. There was one catch: He was afraid of heights and looked unaccountably timid in sequences calling for him to climb trees and swing from vines. Fortunately, Winslow Wilson had already shot most of the “aerial” scenes needed and Parsons elected to keep his previous star’s vine-swinging footage in the picture.

Edgar Rice Burroughs felt—correctly—that the bulky Lincoln did not accurately represent the lithe, sinewy Ape Man of his popular stories. But Elmo’s imposing appearance and obvious strength made him convincing in scenes where raw power was called for, such as his wrestling match with a lion. And although ERB squabbled with Parsons repeatedly, he wanted the picture to be a success and publicly lent his support to the venture, posing with Lincoln for publicity photos.

Tarzan of the Apes, many months in production, was a sensation upon its premiere in January 1918. The original version was ten reels in length, with a running time of more than two hours. Parsons trimmed the footage by 20 percent and sent the picture into national release that April. Its success made Elmo Lincoln a star. He reprised the role later that year in a hastily turned out sequel, The Romance of Tarzan, undertaken by Parsons as soon as it became apparent that the first picture was a big hit. (Tarzan of the Apes is said to have grossed more than a million dollars, this at a time when movie theaters charged 10 to 25 cents per ticket.)

The following year Elmo was signed to an exclusive contract by the Great Western Producing Company, whose principals, Julius and Abe Stern, were related by marriage to Carl Laemmle, president of what was then called the Universal Film Manufacturing Company. Lincoln starred in three cliffhanger serials produced by Great Western and released by Universal: Elmo the Mighty (1919), Elmo the Fearless and The Flaming Disc (both 1920). Packed with action, these episodic thrills included frequent scenes of the star getting his shirt ripped off so audiences could see his barrel chest.

When the Weiss brothers-owned Numa Pictures Corporation, which had licensed screen rights to ERB’s The Return of Tarzan, decided to make a serial out of the book, Great Western was contracted to produce the chapter play with Lincoln reprising his star-making role. Enid Markey had played Jane in the first two features but was replaced by younger, prettier Louise Lorraine in the serial, which was titled The Adventures of Tarzan. A hectic, action-packed affair, it reached the nation’s screens in December 1921 and was quite profitable, although not as much as Tarzan of the Apes had been.

For reasons still not easily determined, Elmo’s career virtually dissolved in the years after Adventures of Tarzan. By 1923 he was reduced to playing an unbilled supporting role in The Hunchback of Notre Dame with Lon Chaney. He appeared in just a handful of bit parts before securing his last leading role, in the 1927 Rayart serial King of the Jungle. Despite the title, it was not a Tarzan picture; Lincoln played a Great White Hunter type. King was a modest success but did nothing to reverse Elmo’s steady decline. Subsequently he left Hollywood to pursue several business ventures.

Lincoln returned to motion pictures in 1939, making frequent appearance in “B” Westerns starring the likes of Gene Autry, George O’Brien, and Charles Starrett. Ironically, he also won small roles in a brace of later films featuring ERB’s Ape Man: Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942, starring Johnny Weissmuller) and Tarzan’s Magic Fountain (1949, starring Lex Barker). Publicity materials for both movies played up Elmo’s association with the character.

The screen’s first Tarzan died on June 27, 1952, at the age of 63. He had a heart attack in the middle of a coughing spell.

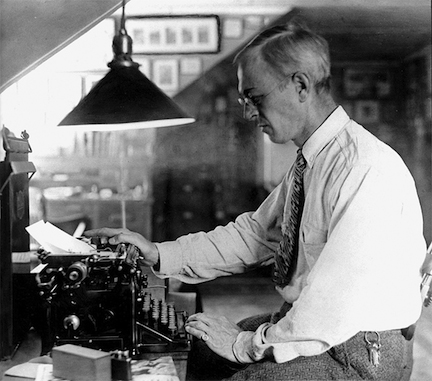

Birthday Boy: Clarence E. Mulford

Western fiction’s most enduring hero was the offspring of a mild-mannered, bespectacled civil servant who spent his leisure hours writing about a mythical frontier from the confines of a modest Brooklyn apartment. The author was Clarence Edward Mulford, and the literary figure he sired was Hopalong Cassidy. Hoppy and his Bar-20 comrades first appeared in a short story, “The Fight at Buckskin,” published in the December 1905 issue of Outing Magazine. Today we celebrate the birthday of that prolific writer, whose work mostly (but not exclusively) appeared first in pulp magazines.

Born on February 3, 1883 in Streator, Illinois, Clarence Mulford grew up in a solidly middle-class household. Small of frame, quiet, and introverted, Clarence was an indifferent student with limited social skills and a disdain for athletics. His principal interest was the Wild West—or, at least, the Wild West depicted in the lurid dime novels of that era. He read in prodigious quantities the almost wholly fictitious exploits of Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, and Kit Carson, living vicariously through their adventures. After graduating from high school he toiled in several humdrum jobs before finding steady work as a civil servant, dispensing marriage licenses in Brooklyn, New York.

As a young man Mulford was animated by two passions: physical fitness and writing. Weight training and roadwork developed his undersized body; putting pen to paper developed his mind. “The Fight at Buckskin” wasn’t the first story he wrote, but it was the first he sold. This 6,250-word yarn introduced Outing readers to the scrappy cowpunchers of the Bar-20, a Texas cattle ranch managed for an Eastern syndicate by foreman Buck Peters. His loyal “waddies” included Red Connors, Johnny Nelson (also known as “the Kid”), Lanky Smith, Skinny Thompson, Pete Wilson, Billy Williams, and a particularly colorful gent known as Hopalong Cassidy.

The Cassidy of Mulford’s early stories is a raucous cowboy whose habits certainly wouldn’t make him welcome in polite society. He’s an inveterate tobacco chewer (and spitter) prone to swearing and fond of concocting creative insults good-naturedly directed at his fellow punchers. Described in an early story as “passably good-looking,” Hopalong sports a thatch of unruly red hair and typically wears the faded denims, chaps, and broad-brimmed sombreros common to working cattlemen. He can be volatile now and then, but for the most part he’s a cool character with a keen mind and a general’s sense of strategy. Like all his comrades at the Bar-20, he puts a high premium on loyalty. “The Fight at Buckskin” revolves around an all-day gunfight occasioned by the killing of one Jimmy Price, Buck’s youngest puncher.

Although Mulford was not a particularly distinguished writer—his prose was often stiff and formal, as per the Victorian style prevalent in the early 20th century—his Bar-20 yarns had the ring of authenticity. His early interest in the Wild West of dime novels had metamorphosed into a fascination with Western history, and he built a reference library that consisted not only of books written about the frontier, but also a library of file cards bearing data he gleaned from countless magazine articles and newspaper accounts. (Eventually he amassed more than 17,000 file cards, the largest such collection ever assembled by a single researcher.)

Mulford’s tales were accurate with regard to history, location, and the minutiae of ranch life, but the principal characters in the Bar-20 saga bore little resemblance to real working cowhands in the late 19th century. From the first, Hoppy, Buck, and the others were mythical figures comparable to Odysseus and his adventurers, or to the knights of Arthurian legend. Hardly perfect men, they nonetheless adhered to a rigid moral code and used violence primarily to achieve rough justice in a region of the country not yet bound by the rule of law.

For several years following publication of “The Fight at Buckskin,” the Bar-20 saga unfolded in short stories. In June of 1907, Mulford began writing his first novel-length installment in the series. He discarded two drafts before completing the manuscript in March, 1909. Hopalong Cassidy was published exactly one year later by Chicago’s A.C. McClurg & Co. The novel focused on the feud between the Bar-20 and an adjoining ranch, the H2, with a subplot detailing Hopalong’s romance with Mary Meeker, mistress of the rival cow outfit. Lengthy, episodic, and packed with supporting characters, the book didn’t overly impress critics but achieved considerable success nonetheless; McClurg went through six hardcover printings in the first year alone.

Mulford gradually eased up on short-story production and concentrated on cranking out book-length yarns. Hoppy wasn’t always the focal point of these; Buck Peters, Johnny Nelson, and reformed gambler Tex Ewalt (an early antagonist of the Bar-20) each “starred” in novels using their names in the titles. In 1923 Mulford transferred his allegiance from McClurg to Doubleday, and that house published his subsequent novels in hard covers after serializing most of them in its pulp magazines Short Stories and West. While not blockbuster best-sellers, Mulford’s books attracted a fairly large, faithful following that guaranteed consistent sales for Doubleday. Over the years the New York-based publishing house developed a warm relationship with Mulford, which directly resulted in Hopalong Cassidy being brought to the silver screen. Readers of this blog, Blood ‘n’ Thunder, and my other publications know how fond I am of the Hoppy films, which have been discussed in this space before and doubtless will be again.

A staunch small-government conservative, Mulford hated paying a huge percentage of his earnings in income tax, so after completing Hopalong Cassidy Serves a Writ in 1941 he stopped writing altogether. Royalty payments on his books and licensing fees from Hollywood enabled him to live comfortably, and in fact he became wealthy in the early Fifties from his small percentage of the revenue generated by sales of licensed Hopalong Cassidy consumer products. Ever the prudent steward of resources, Mulford continued to enjoy a modest lifestyle. He died in 1956 at age 72.

Mulford’s fiction shows its age more so than the works of many contemporaries. But he remains readable, and at their best his yarns have about them an almost magical aura. The Hoppy about whom he wrote is a larger-than-life figure despite the author’s efforts to make him seem like an ordinary cowhand with a good head for strategy. In recent years several early Bar-20 books have been reprinted in paperback, and I recommend them to fans of pulp fiction in general and Westerns in particular.

Birthday Boy: Johnston McCulley

Today we celebrate the birthday of Johnston McCulley, the creator of Zorro and one of the giants of pulp fiction. Born and raised in Illinois, he began his literary career as a crime reporter for The Police Gazette. McCulley turned to fiction writing in 1906 and made his pulp-magazine debut in the June issue of The Argosy. Over the next few years he cracked other Munsey pulps—The All-Story, Railroad Man’s Magazine—sold to Blue Book, and started writing for Street & Smith with yarns in Top-Notch.

In 1915, at the age of 32, he became one of the regular contributors to Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, which evolved from the Nick Carter nickel weekly. The first of McCulley’s many series characters for that periodical was Black Star, a criminal mastermind who wore a cloak and a hood with a jet-black star on the forehead. These stories appeared under the pseudonym John Mack Stone, the first of many pen names McCulley used. (Others included Harrington Strong, Raley Brien, George Drayne, and Walter Pierson.) Although Black Star was a thoroughgoing villain, most of McCulley’s recurring characters in DSM were avenging angels or modern Robin Hoods—always working outside the law but committed to serving the interests of justice. Among them were The Thunderbolt, the Avenging Twins, the Man in Purple, and the unaccountably popular Crimson Clown. McCulley also score with Thubway Tham, a lisping pickpocket whose often-humorous exploits were chroncled first in DSM and later in Best Detective, a Street & Smith reprint title.

To the best of my knowledge, McCulley rarely if ever employed pseudonyms for his submissions to Argosy and All-Story Weekly. It was for the latter magazine that he created his most famous pulp hero, Senor Zorro, who first appeared in “The Curse of Capistrano,” a book-length novel serialized in five parts during the summer of 1919. The basic idea, involving a daring hero who poses as a foppish aristocrat, had already been used by Baroness Orczy in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905), but where her story unfolded in Europe during the French Revolution McCulley set his in Old California during the late 18th century.

The initial Zorro adventure was clearly intended as a one-off, since at story’s end the character was unmasked and (presumably) headed for matrimony. But McCulley struck it rich when popular motion-picture actor Douglas Fairbanks licensed the novel for adaptation as his first self-produced, big-budget swashbuckler. The resulting film, The Mark of Zorro (1920), was an international sensation that boosted Fairbanks into stardom’s top rank. On the strength of its success McCulley quickly wrote and easily sold “The Further Adventures of Zorro” (1922), serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly. “Curse of Capistrano” was published in hard covers by Grosset & Dunlap in 1924, retitled The Mark of Zorro to capitalize on the film. In 1925 Fairbanks produced and starred in a sequel, Don Q, Son of Zorro, which simply grafted McCulley’s character onto an adaptation of Hesketh and Kate Prichard’s “Don Q’s Love Story.”

McCulley wrote other high-adventure yarns with similar settings and Zorro simulacrums, but none seemed to have the same appeal. The original returned in a 1931 novel, Zorro Rides Again, also serialized in Argosy. Over the next few years he popped up in a handful of uncollected novelettes. The author had pretty good luck selling his other pulp stories to Hollywood, but he hit pay dirt again when Republic Pictures licensed the character for a 1936 feature film (The Bold Caballero) and a series of cliffhanger serials: Zorro Rides Again (1937), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Zorro’s Black Whip (1944), Son of Zorro (1947), and Ghost of Zorro (1949). Their mutually beneficial relationship was not affected by the 1940 release of a lavish 20th Century-Fox remake of The Mark of Zorro; Fox had purchased remake rights to the 1920 film from Fairbanks, but McCulley retained his hold on the character and gave Republic free rein to use Zorro in any way the studio deemed useful, as long as it didn’t attempt to adapt “Curse of Capistrano.”

The Fox film, which starred Tyrone Power, Linda Darnell and Basil Rathbone, made Johnston McCulley hot again and he was able to sell one last novel, “The Sign of Zorro,” to Argosy for serialization during 1941, as The Mark of Zorro was playing in the nation’s movie theaters. In 1944 he parlayed the character’s continuing popularity into a series of short stories for the Thrilling Group’s West, which had become a mundane pulp magazine. The Zorro series ran in West for seven years, and during that time McCulley revived his Detective Story Magazine characters Thubway Tham and The Crimson Clown for Thrilling’s detective pulps.

West lasted only a couple more years after dropping the Zorro series in 1951. Pulp magazines were dying, and after nearly a half-century of fictioneering Johnston McCulley was pretty well written out. He made sporadic short-story sales over the next few years but might easily have been forgotten but for Walt Disney’s 1957 licensing of Zorro for a TV series broadcast over the ABC network. Zorro was a huge hit that lasted for three seasons and continued to earn good ratings for years afterward in syndication.

McCulley died in 1958, having lived long enough to see his most famous creation revived for a new generation. I suspect he’d be amazed to learn that, another 50 or so years later, Zorro is still going strong in movies and on television.

On the basis of volume alone Johnston McCulley could be considered a hack. A fair percentage of his output was bland, trite, and/or repetitive. His various Detective Story series abound with familiar situations and character types, and like most high-volume producers who were active for a prolonged period, his later yarns cannibalized earlier ones. But like other pulp writers who enjoyed comparable longevity, McCulley was a natural storyteller whose stories, whatever their flaws, were never unreadable. He never lost sight of the quality that endeared him to editors: his ability to provide the masses with escapist entertainment. Altus Press and Wildside Press, to name just two specialty publishing houses, have reprinted some of his works. I recommend giving them a try.

Flashback Friday: 1998 Pulpcon

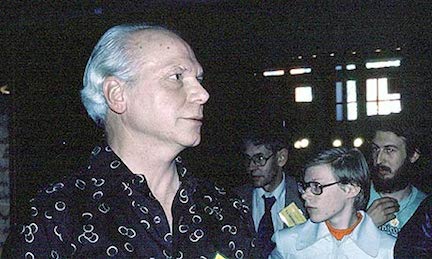

Having just come across some long-buried photos in the Blood ‘n’ Thunder archives, and with nothing better to post here today, I’m attaching a handful of shots from Pulpcon 27, which was held in July 1998. This was either the last or next to last Pulpcon held at the university in Bowling Green; my memory is a little fuzzy as to which. As I recall, that summer in Ohio was hot and humid, but the convention attendees were nice and cool in the auditorium crammed with vintage pulps, books, and related collectibles. I was still a newbie to pulp fandom but made many new friends that year — folks I still see regularly at PulpFest, the Windy City con, and other events geared to book and magazine collectors.

My friend Rob McKay took the pictures you’ll see below, and many more as well. But the other photos are missing in action. Perhaps I’ll be able to turn them up yet.

To start with, here a bird’s eye view of the dealer room:

I had purchased a dealer table that year but sold all my (limited) wares in fairly short order. The shot below was probably taken on the last afternoon of the show as things were winding down. Jerry Peters (left) and I are listening intently to an unidentified speaker. I’m fairly, but not totally, certain that Joe Rainone is doing the talking.

In the next shot I’m making a trade with veteran dealer/collector Dick Wald, who’s inspecting the quality of my offering. That’s Shadow collector Lisa Kwaterski next to me. As I recall, 1998 was the year that Dick brought a huge stock of recently acquired Shadow pulps. He made the mistake of inviting a friend to his hotel room to check them out the night before the show started. Word got around and before Dick could do anything about it, he had a bonafide feeding frenzy on his hands as collectors swarmed into his room uninvited. I remember forking over $1500 to him that night.

Another bird’s eye view, with me in the middle brandishing my newly acquired treasure from the trade with Dick.

Finally, here’s a shot of my good buddy and Weird Tales/Arkham House specialist Dave Kurzman, looking characteristically mellow behind his table. Dave always brings top-notch stuff to the conventions, and I’m already looking forward to seeing what he’ll unveil at the upcoming Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention.

Hey, this was fun. I’d like to do more “Flashback Friday” posts of this sort, so if you’re willing to share any photos from pulp conventions of the past, please feel free to send me some scans. Meanwhile, I’ll see what else I can dig up….

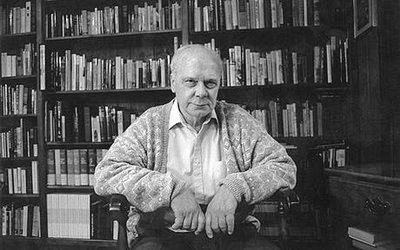

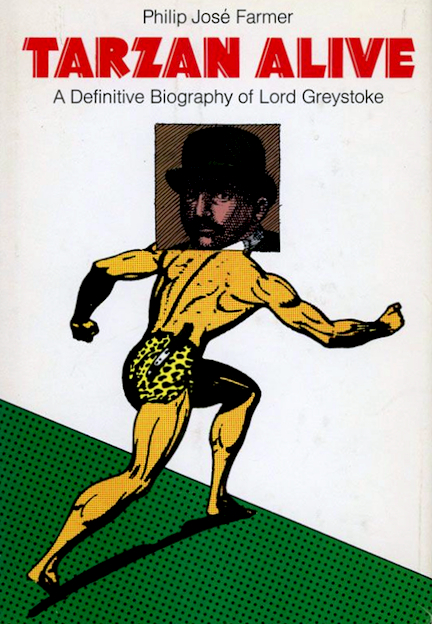

Birthday Boy: Philip José Farmer

Were he still with us, Philip José Farmer today would be celebrating his 97th birthday. As it was, he had a pretty long run, passing in early 2009 shortly after turning 91. I suspect he’s best remembered by readers of this blog and Blood ‘n’ Thunder as the author of Tarzan Alive (1972) and Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life (1973), fanciful “biographies” of those enduring pulp-fiction creations and the seminal works establishing what has come to be known as the “Wold Newton Universe.” To others, especially those in the science-fiction community, he’s probably regarded more highly for two multi-novel sagas, one revolving around the World of Tiers (1965-93) and the other around Riverworld (1971-83). The latter, which always appealed to me, posits the existence of a planet over which winds a huge river valley populated by resurrected Earthlings.

Farmer certainly deserves kudos for those works, but he also merits recognition as (in my opinion) the last major science-fiction writer to get his start in pulp magazines. He broke into print with “O’Brien and Obrenov,” a short story in the March 1946 issue of Adventure, but it was “The Lovers,” a novella first published in the August 1952 Startling Stories, that attracted attention and marked him as a comer.

Under the editorship of Samuel Mines Startling had moved beyond the adolescent space opera of its early years and was publishing a better grade of speculative fiction. When he purchased Farmer’s provocative story Mines had to have known it would create a sensation, which is exactly what happened. For those who don’t know, “The Lovers” revolves around the romance and sexual relationship between a male human and a female extraterrestrial (with humanoid characteristics, of course). Previous SF writers had avoided sexual themes and few pulp editors would have countenanced publishing such a story, but the tyro’s mature, thoughtful treatment of this subject matter disarmed Mines. With “The Lovers” Farmer made what arguably was the most audacious debut in the genre’s history. Although it’s now more than 60 years old, the story holds up beautifully and can be enjoyed even by readers unaware of its historical significance.

“The Lovers” won Farmer a richly deserved 1953 Hugo Award for Most Promising New Talent. It was followed by “Moth and Rust” (Startling Stories, June 1953), an equally assured story that didn’t have quite the same impact as its predecessor. But Farmer was on his way, and in subsequent SF works he frequently displayed the same audacity and inventiveness that had distinguished his maiden effort. He wrote for pulps and digests alike, expanding both “The Lovers” and “Moth and Rust” in the early Sixties to market them as paperback originals.

“The Lovers” won Farmer a richly deserved 1953 Hugo Award for Most Promising New Talent. It was followed by “Moth and Rust” (Startling Stories, June 1953), an equally assured story that didn’t have quite the same impact as its predecessor. But Farmer was on his way, and in subsequent SF works he frequently displayed the same audacity and inventiveness that had distinguished his maiden effort. He wrote for pulps and digests alike, expanding both “The Lovers” and “Moth and Rust” in the early Sixties to market them as paperback originals.

Phil Farmer never made any secret of his affection for the pulp-magazine heroes of his youth, and in 1969 he wrote a still-controversial novel, originally published in wraps by Essex House, that seemed to poke fun at two of them. A Feast Unknown featured thinly disguised simulacrums of Tarzan and Doc Savage, dubbed Lord Grandrith and Doc Caliban respectively. Farmer made them half-brothers — their father being Jack the Ripper (!) — initially at odds but eventually allied against a mutual adversary bent on world domination. Farmer larded the novel with extremely graphic scenes of sex and violence, alienating some readers but dazzling others with its — there’s that word again — audacity. Two sequels, Lord of the Trees and The Mad Goblin, followed in 1970.

The Grandrith/Caliban series led to Farmer’s ersatz biographies of Tarzan and Doc Savage, which established a genealogical connection between the two and sparked development of what PJF scholar Win Scott Eckert later dubbed the “Wold Newton Universe,” so named for the small Yorkshire village where a meteorite fell in 1795. According to Farmer, the highly radioactive fragment contaminated the occupants of a passing coach nearby and produced genetic mutations in their progeny. Eventually he incorporated into the Wold Newton extended family such popular pulp characters as The Shadow, G-8, The Spider, Sam Spade, and The Avenger, as well as Doc and Tarzan. He also proposed genetic linkages to other favorites of mystery and adventure fiction, including Sherlock Holmes (and his nemesis, Professor Moriarty), Fu Manchu (and his nemesis, Nayland Smith), Raffles, Allan Quatermain, Solomon Kane, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Nero Wolfe, James Bond, and others too numerous to list in this space. The “Universe” also is home to fictional characters not descended from the coach occupants affected by the 1795 meteor strike.

Another controversial product of Farmer’s inventiveness was Venus on the Half-Shell, a 1974 novel serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction prior to its publication the following year as a paperback bylined to Kilgore Trout, a fictional scrivener created by Kurt Vonnegut for his 1965 novel God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. Trout, who made appearances in subsequent Vonnegut yarns, is described as a science-fiction writer who sells primarily to cheesy porn magazines. Farmer had the idea of expanding a story fragment referred to in Mr. Rosewater. He approached Vonnegut for permission, which was granted, but the Slaughterhouse Five author reportedly disliked Venus on the Half-Shell and resented its being assumed to be one of his own stories. Farmer later claimed that Vonnegut angrily chewed him out in a profanity-laced phone call.

During his lengthy career Philip José Farmer won three Hugos, the 2000 Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, and the 2001 World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement. All told he authored nearly 60 novels and over 100 shorter works of fiction. His many essays and articles appeared in pro and fan publications alike.

Today, his output — especially the Wold Newton material — is analyzed and celebrated by a small but dedicated cadre of enthusiasts, some of whom assemble yearly at an event known as Farmercon. In recent years, Farmercon has operated under the auspices of PulpFest, an annual gathering of pulp-fiction enthusiasts that’s familiar to Blood ‘n’ Thunder readers. The contributions of Farmercon attendees to PulpFest are always interesting, and if you plan on joining us in Columbus this August, consider sitting in on their panels and presentations. They do a bang-up job of keeping the PJF flame burning.

Viva THRILLING WONDER STORIES!

I recently updated the site’s Collectibles For Sale section, and among the newly added items were a half dozen or so issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories from the late Forties and early Fifties. It’s been a good many years since I read the copies in my own collection, but after listing these duplicates I flipped through them and was reminded just how much fun they are.

Thrilling Wonder Stories and its sister magazine, Startling Stories, had always been fun, but they made great strides in the immediate aftermath of World War II under the editorship of Sam Merwin. He deemphasized their juvenile aspects — such as the hokey letter columns presided over by “Sergeant Saturn” — and gradually introduced a more mature type of science fiction. Startling continued to run book-length novels and TWS continued to run a mix of novelettes and short stories, but each began to eschew adolescent space opera in favor of more thoughtful and mildly provocative yarns. Humor and irony were found with increasing frequency, as were stories that ended on poignant or downbeat notes.

What’s really striking about the late Forties-early Fifties TWS is the roster of regular contributors. Practically every issue from this period boasts an all-star author lineup. You see the same names over and over on the covers and contents pages: Ray Bradbury, John D. MacDonald, Fredric Brown, L. Ron Hubbard, Robert A. Heinlein, Henry Kuttner, Leigh Brackett, Murray Leinster, Jack Vance, L. Sprague de Camp, and so on. You have the series of novelettes by Raymond F. Jones that were later adapted to film as This Island Earth. Believe me, there’s plenty of great reading in this period of the magazine’s history. Not every author is represented in every issue by a classic yarn; after all, TWS was far from the best paying market for SF. But the overall average is quite high. And even though they were controversial at the time (readers mostly disliked them), those “Good Girl Art” covers by Earle Bergey certainly make the magazine distinctive.

Anybody who enjoys pulp SF should have a few representative issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories in his or her collection. If you’re of a mind to sample this long-running, generally meritorious magazine, I strongly suggest beginning with the selection for sale elsewhere on this site.

Happy Birthday, Two-Gun Bob!

On this day in 1906, in the small Texas town of Peaster, Robert Ervin Howard was born. Growing up in the Lone Star State, deeply attached to his sickly, possessive mother, he took his own life 30 years later as she lay on her deathbed. By that time he had become a modestly successful writer of pulp fiction. Today, nearly eight decades after his passing, Robert E. Howard is considered one of the form’s giants, his works most ardently championed by generations of readers not yet born when the last appeared in a rough-paper magazine.

Like so many of his present-day fans, I first encountered REH (as he is popularly known) in 1966 when Lancer Books, at the urging of fantasy/science-fiction writer L. Sprague de Camp, began reprinting the adventures of Howard’s most famous creation, Conan the Barbarian. At the time I was 13, just an eighth-grader, but already a voracious reader and an avid consumer of vintage pulp fiction via the medium of mass-market paperbacks. I’d already devoured the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs reissued by the publishing houses Ace and Ballantine, as well as the former’s reprints of pulp science fiction. I’d also read most of Sax Rohmer’s tales (reprinted by Pyramid), had recently consumed the book-length yarns of “hard-boiled” detective-fiction scribes Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, and waited with breathless anticipation for each new Bantam reprint of a Doc Savage story.

But that first Lancer paperback, Conan the Adventurer, promised a reading experience unlike any I had enjoyed up to that time. The Frank Frazetta cover — showing Conan post-battle, surrounded by corpses and with a near-naked wench at his feet — promised something new and exciting. My classmates didn’t always share my taste in fiction (many of them didn’t read anything but comic books for enjoyment), but I remember several of them buying Adventurer after getting a glimpse of my copy. Howard’s extraordinarily vivid prose, especially his bone-crunching action sequences, really spoke to us. Especially since we 13-year-old boys were little more than barbarians ourselves, with our own fantasies of blood-thirsty adventures and nascent yearnings for those voluptuous wenches to be found loitering on battlefields after the defeats of evil wizards and power-mad monarchs.

I bought the subsequent Conan paperbacks as fast as they hit local bookstores, staying with the series after Lancer closed up shop and Ace assumed the responsibility of completing it. At the time I didn’t pay much attention to de Camp’s manipulation of the original material, and it didn’t particularly bother me that he and Lin Carter were adding their own entries to the canon. Frankly, by the time I’d finished the 12th and final volume, 1977’s Conan of Aquilonia, I’d had enough of the Cimmerian, the wizards, and the wenches. It was many years before I attempted to read anything else by Howard.

Later, after becoming obsessed with pulp fiction, I sought out much of the remaining REH material — not just his other fantasy and sword & sorcery fiction for Weird Tales, but also his Westerns, spicy yarns, sport stories, and straight adventure fiction. I still haven’t read his entire output, but I’ve put quite a dent in it. Much of his stuff is appealing to me, although some of it is plainly hackwork that I’ll never revisit. But he’s one of the storytellers whose oeuvre is essential to an understanding of the blood-and-thunder tradition in American popular fiction. This evening, on the occasion of his 109th birthday, I plan on rereading one of his yarns. Many of you who follow this blog are doubtless Howard fans to a greater or lesser extent, so I imagine I won’t be alone.

Windy City 2015 Film Program

Our 125th birthday tribute to H. P. Lovecraft extends to movies and TV episodes adapted from his classic pulp stories. Amazingly, it took four decades for Hollywood to discover HPL: the first Lovecraft film, 1963’s The Haunted Palace, flashed on the nation’s big screens fully 40 years after publication of his first story in Weird Tales. And relatively few of the Master’s yarns were translated to celluloid until the late Nineties, when the floodgates opened. For this year’s Windy City Film Festival we’ve assembled a representative sampling of HPL movies. Friday’s lineup is devoted to the Lovecraft-themed output of writer-director Stuart Gordon, who brought mainstream attention to the creator of Cthulhu with his 1985 hit Re-Animator, nominally based on “Herbert West, Reanimator.” Saturday’s lineup is a cross-section of other notable adaptations.

It should be noted that most of the films we’re running this year’s show are either R-rated or unrated and contain occasional scenes of gore and nudity, making them potentially unsuitable for attendees with children.

FRIDAY

12:00 pm — Dagon (2001) 98 minutes.

Despite the title, this Spanish-made film actually adapts HPL’s “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.” A boating accident off the coast of Spain finds Paul Marsh (Ezra Godden) and his girlfriend Barbara (Raquel Merono) looking for help in the ramshackle fishing village of Imboca. As night falls, people start disappearing and a shroud of unseen menace hangs over the community. Paul and Barbara, pursued by the entire town, learn Imboca’s dark secret: that its residents worship Dagon, a monstrous sea god of ancient origin. The film got mixed reviews, although AllMovie critic Jason Buchanan said, “Lovecraft fans will most likely be willing to forgive Dagon‘s shortcomings in favor of a film that obviously shows great respect and appreciation for its source materials.” And Film Threat‘s K. J. Doughten opined, “While not a perfect movie, Dagon crams its wild, over-the-top concepts down our throats with so much conviction that we can’t help but get swept along for the ride.”

01:45 pm — Castle Freak (1995) 95 minutes.

Stuart Gordon’s version of HPL’s “The Outsider” was produced by the father-son team of Albert and Charles Band, whose Full Moon Entertainment supplied most of the direct-to-video horror movies that flooded rental-store shelves during the Nineties. In a nod to that market, Gordon included some elements of the “splatter” school, including one surprisingly brutal sequence that Lovecraft would have abhorred. But the film is not without merit; in fact, it’s more serious and mature than the lurid VHS packaging would have one believe. After inheriting a 12th-century castle that belonged to a notorious Duchess, John Reilly (Jeffrey Combs), wife Susan (Barbara Crampton), and their blind teenage daughter Rebecca (Jessica Dollarhide) relocate to Italy. The family is a troubled one: Susan blames John for the death of their son in the drunk-driving incident that also cost their daughter her sight. On the advice of the executor, the Reillys decide to stay at the castle until the estate can be liquidated. Unbeknownst to them, a freakish monster remains locked in the basement. This was the third and last HPL-inspired feature film on which Gordon, Combs, and Crampton collaborated.

03:30 pm — From Beyond (1986) 85 minutes.

Following the surprise success of his first Lovecraft adaptation, Re-Animator, Stuart Gordon was inspired to make a series of HPL films with the same stars, along the lines of American-International’s Edgar Allan Poe series directed by Roger Corman. From Beyond, loosely based on a short story of the same title, reunited Re-Animator cast members Jeffrey Combs and Barbara Crampton. It centered on a pair of scientists attempting to stimulate the pineal gland with a device called “The Resonator.” An unforeseen result of their experiments is the invasion of Earth by creatures from another dimension. They capture the head scientist and whisk him away to their world, returning him as a grotesque shape-changing monster that preys upon others at the laboratory. Shot in Italy to save money, From Beyond boosted the previous film’s the gore quotient and included some S&M content that the MPAA objected to. Gordon was forced to re-cut several sequences and completely eliminate some five minutes of footage. The missing scenes were restored in 2007 and we are running the original director’s cut.

Immediately Following Auction — Dreams in the Witch House (2005) app. 50 minutes.

One of Lovecraft’s most memorable yarns gets fine treatment by HPL aficionado Stuart Gordon. It originally aired on American TV on November 4, 2005 as the second episode of Masters of Horror. University student Walter Gilman (Dagon‘s Ezra Godden) moves to a cheap room in an old boarding house. He hears shrill screaming and rushes to help his neighbor, Frances (Chelah Horsdal), when she is menaced by what appears to be a large rat. Walter becomes close with Frances and even lends her money to keep her in the boarding house. A neighbor warns the student that the house is evil—and that his room houses something unspeakably evil. Gordon’s adaptation streamlines the story somewhat and gives it a contemporary setting, but the essential elements remain intact and overall Dreams in the Witch House is quite effective.

SATURDAY

10:00 am — The Haunted Palace (1963) 87 minutes.

We’re running this American-International release starring Vincent Price because it was the first feature film that brought Lovecraft to the screen. Ostensibly another of Roger Corman’s popular and profitable Edgar Allen Poe adaptations, it’s actually derived from HPL’s “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.” In their book Lurker in the Lobby: A Guide to the Cinema of H. P. Lovecraft, Andrew Migliore and John Strysik write: “The Haunted Palace is a seminal film for Lovecraft lovers; it is the first major motion picture to introduce [Lovecraft’s] creation[s]—the Necronomicon, and those cosmic abominations Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth—to a general audience. [Lovecraft’s] obsession with the past is clearly presented, and in a heartfelt passage at the end of the film, so is his belief that mankind is a minor species adrift in a malevolent universe. The film strikes a good balance between narrative and action, and Vincent Price is, well, priceless as Ward/Curwen. The supporting cast is solid and the art direction by Daniel Haller is really quite good for such a low-budget film. Roger Corman did an admirable job as the first American feature-film director to stake out some cinematic high ground for the cosmos-crushing adaptations of [H. P. Lovecraft] to follow.” We’re also running Dan O’Bannon’s 1992 take on “Charles Dexter Ward,” The Resurrected, but the two movies are strikingly different, though each excellent in its own right.

11:45 am — H. P. Lovecraft’s Necronomicon: To Hell and Back (1993) 96 minutes.

An American-made anthology film, Necronomicon was produced in 1993. It was directed by Brian Yuzna, Christophe Gans and Shusuke Kaneko and was written by Gans, Yuzna, Brent V. Friedman, and Kazunori Itō. It stars Bruce Payne , Richard Lynch, Jeffrey Combs (who plays Lovecraft himself in a newly devised framing story), Belinda Bauer, and David Warner. Three segments are based on a trio of Lovecraft classics: “The Drowned” comes from “The Rats in the Walls”, “The Cold” from “Cool Air,” and “Whispers” from “The Whisperer in Darkness.” A film-festival favorite released in home-video formats, Necronomicon did quite well in America but was even more profitable in European and Asian markets. Truth be told, two of the film’s three segments leave a little something to be desired, but we’ve included Necronomicon because it enables us to present three Lovecraft tales for the price of one, so to speak. And “The Drowned” really is quite good.

01:30 pm — The Dunwich Horror (1970) 91 minutes.

This drive-in favorite released by American-International Pictures attained considerable notoriety for a supposed topless scene featuring top-billed Sandra Dee, the screen’s original “Gidget” and a squeaky-clean teen idol. (Actually, a body double was used for the shot.) But Dunwich Horror also familiarized American audiences with key elements of the Cthulhu Mythos and therefore warrants inclusion in our lineup. The film opens at the fictional Miskatonic University in Arkham, Massachusetts, where Dr. Henry Armitage (Ed Begley) has just finished a lecture on the sinister Necronomicon. He gives the book to his student Nancy Wagner (Dee) to return to the University library. She is followed by a stranger, who later introduces himself as Wilbur Whateley (Dean Stockwell). Using his hypnotic gaze, Whateley persuades Nancy to give him the terrible tome, with which he hopes to unleash ancient and malevolent forces. Clearly an AIP attempt to capitalize on the phenomenal success of 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, this neatly turned out Lovecraft adaptation takes liberties with the original but replicates the oppressive, unwholesome atmosphere of timeless horror.

03:15 pm — The Resurrected (1992) 108 minutes.

Directed by Dan O’Bannon (screenwriter of Alien and long-time horror/SF filmmaker), this is an adaptation of “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.” Claire Ward (Jane Sibbett) hires private investigator John March (John Terry) to look into the increasingly bizarre activities of her husband Charles Dexter Ward (Chris Sarandon). Ward has become obsessed with the occult practices of raising the dead once practiced by his ancestor Joseph Curwen (Sarandon in a dual role). As the investigators dig deeper, they discover that Ward is performing a series of grisly experiments in an effort to actually resurrect his long-dead relative Curwen. In their book Lurker in the Lobby: A Guide to the Cinema of H. P. Lovecraft, Andrew Migliore and John Strysik write: “The Resurrected is the best serious Lovecraftian screen adaptation to date, with a solid cast, decent script, inventive direction, and excellent special effects that do justice to one of [Lovecraft’s] darker tales.”

Immediately Following Auction — The Call of Cthulhu (2005) 47 minutes.

This lovingly crafted adaptation of the seminal Cthulhu Mythos story was produced, written, and directed by the team of Andrew Leman and Sean Branney for distribution by the HPL Historical Society. In a bold but inspired move, Leman and Branney filmed it as a black-and-white silent movies and employed for its special visual effects only such techniques as would have been available to filmmakers in 1926, when the yarn was published in Weird Tales. Extremely faithful to HPL’s original, The Call of Cthulhu has found almost universal favor with Lovecraft lovers. Andrew Migliore and John Strysik write: “The Call of Cthulhu is a landmark adaptation that calls out to all Lovecraftian film fanatics—from its silent film form, its excellent cast, its direction, and its wonderful musical score … this is Cthulhuian cinema that Howard would have loved.” We ran the film several years ago but feel it’s worth repeating as a superb HPL adaptation.

The Overstock Sale Has Ended

Thanks to those of you who purchased books during the Overstock Sale that was underway this past week. Technically, the sale is still underway as I write these words on Friday afternoon, but in actuality I’ve just terminated it because all available copies of the five advertised items are gone. In fact, I didn’t have enough on hand to meet all orders, but I decided to honor purchases made through yesterday afternoon by ordering up new copies. So a few of you will receive two shipments: one from me and one from my printer. All orders have now been processed, and any books that haven’t already been shipped will go out early next week.

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net