EDitorial Comments

Birthday Boy: Hiram S. Brown, Jr.

Born on this day in 1909: Hiram S. Brown, Jr., whose career as a motion-picture producer lasted less than two years but gave us some of the finest serials made and released by Republic Pictures. Personally, I think he’s an unsung hero of serial history. A graduate of Princeton and Harvard Business School, “Bunny” (as he was known to friends) was the son of a former head of RKO. That probably helped him get a job at Republic, where he initially worked as a purchasing agent. In 1939 he was made producer of the studio’s serial unit, whose staff directors were William Witney and John English. Together they turned out eight classic chapter plays. They are, in chronological order, Zorro’s Fighting Legion, Drums of Fu Manchu, Adventures of Red Ryder, King of the Royal Mounted, Mysterious Doctor Satan, Adventures of Captain marvel, Jungle Girl, and King of the Texas Rangers.

In my opinion, Bunny has never gotten as much credit as he deserved for the unusually fine quality of these episodic thrillers. He pushed the writers to devise novel situations and inventive chapter endings whenever possible. He fought to use as villains such prominent A-list character actors as Henry Brandon and Eduardo Cianelli, even though they cost Republic more than the usual serial and B-picture heavies. He supported Witney and English when they asked for additional time and resources. He did battle with the front office to add another two weeks to the schedule of Drums of Fu Manchu, allotting the extra time to cinematographer William Nobles for eerie lighting effects on interior scenes. After making his first serial he eschewed use of the hated “recap chapters” (which included flashbacks to earlier episodes) to save money; instead he found other ways to economize. As World War II approached, Bunny left Republic to take a commission in the U.S. Signal Corps. He served with distinction but did not return to producing after the war’s end. But the eight serials he produced for Witney and English are still regarded highly by aficionados of the highly specialized form, and deservedly so.

Birthday Boy: John W. Campbell

Born on this day in 1910: John W. Campbell, Jr., the writer and editor who, after Edgar Rice Burroughs and Hugo Gernsback, was almost certainly the most important man in the history of science fiction. That’s hardly a daring appraisal on my part; no less a giant of SF as Isaac Asimov once declared his former editor “the most powerful force in science fiction ever.” Campbell died in 1971, but the intervening four decades haven’t dimmed or diminished his achievements. In fact, he remains a towering figure in the genre’s history while SF’s New Wave, which prospered during his later years and for a time eclipsed the type of science fiction he championed, now seems quaintly dated—like free love and flower power.

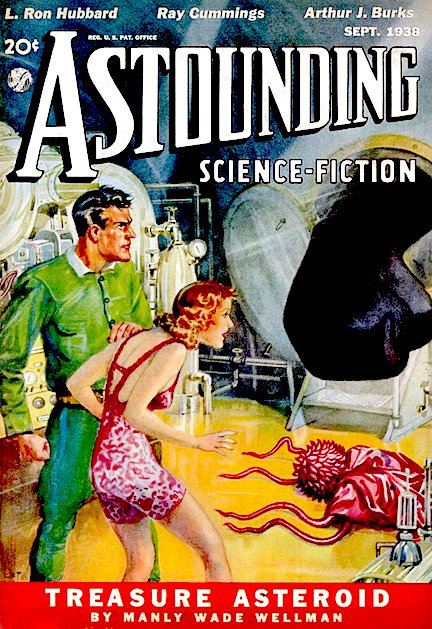

Born in Newark, New Jersey (as I was), Campbell was something of a prodigy who attended MIT and began writing science fiction while still in his teens, breaking into Amazing Stories in 1930 before his twentieth birthday. His early yarns were space operas featuring the heroic trio Arcot, Morey, and Wade. Within a few short years he was producing stories of a more mature nature for Astounding Stories, then edited by F. Orlin Tremaine and published by Street & Smith. “Twilight” (November 1934), a melancholy short story published under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart (a name Campbell used for several years), posited the existence two millennia in the future of a triumphal human race slowly deteriorating for lack of challenge and curiosity. It was a remarkable piece of writing—thoughtful, provocative, far more stimulating than the usual pulp SF fare.

Tremaine published more yarns by Campbell and “Stuart” before making the young writer his assistant editor in 1937. Campbell worked in that capacity for a handful of months, buying most of the magazine’s fiction before becoming Astounding‘s chief editor in early 1938. His high point as Don A. Stuart was reached in the August 1938 issue with the classic “Who Goes There?”, about a shape-shifting alien systematically laying waste to a colony of scientists conducting research in the Antarctic. Most pulp aficionados know that this suspenseful novella has been filmed three times to date: in 1951 as The Thing from Another World, and in 1982 and 2011 as The Thing. Although the latter two are marginally more faithful to Campbell’s original, the first version is by far the most satisfying of the three adaptations.

The next five years saw a flurry of activity that not only made the newly rechristened Astounding Science-Fiction tops in its field but also altered the genre’s history. During this period Campbell bought the first SF stories by writers who would dominate the landscape for decades, among them Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, L. Ron Hubbard, and A. E. van Vogt, to name just a handful. He eschewed the puerile space opera that had filled Astounding‘s pages when it was owned by the Clayton pulp line, demanding that his contributors produce tales which would pass muster for their solid craftsmanship as well as for their grounding in scientific principle.

Occasionally Campbell received from his stable of writers stories that were exceptionally absorbing and well written but utterly lacking in hard science. Some were out-and-out fantasies laced with irony or whimsy. To create a market for these, he persuaded Street & Smith to launch a magazine titled Unknown (later Unknown Worlds), which he also edited. Between 1939 and 1943 this outstanding magazine published some of the finest fantasy and horror stories ever to see print on pulp paper. Loved by its readers and widely respected throughout the industry, Unknown was not a top seller and fell victim to the same wartime paper shortage that forced Astounding‘s reconfiguration to digest size.

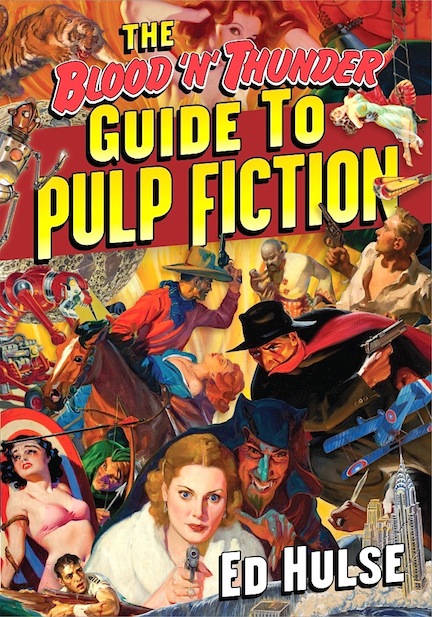

As I’ve written in The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction, Campbell was most influential between late 1937, when he began buying stories for Astounding, and late 1943, when Unknown went under and Astounding began its long, slow decline. Which is not to say that the digest issues didn’t offer many great stories; they did. But the Golden Age had come and gone: Campbell had already introduced and nurtured most of the field’s superstars.

The visionary editor’s judgment began to fail him in the late Forties. He became obsessed with the “fringe science” of psionics, which encompassed such phenomena as psychokinesis and mental telepathy. Despite the absence of hard scientific evidence to support belief in “psi” abilities, Campbell encouraged his regular contributors to submit yarns built around psionics. Some, fearful of losing a well-paying regular market, complied willingly. Others became disenchanted and deserted Astounding for such competing digests as Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Street & Smith had discontinued its line of pulp magazines in 1949, with only Astounding still being published when Condé Nast bought the company in 1959. The following year Campbell changed the magazine’s title to Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction. (This was accomplished after a transition of several months in which each cover’s graphics depicted a different stage of the metamorphosis.) Strong-willed and increasingly didactic, he alienated some former supporters and contributors as the magazine’s prestige diminished. When Campbell died in 1971 he was succeeded by Ben Bova, who in 1978 relinquished the editorial reins to Stanley Schmidt, who held them until 2012. Analog survives still, with this month’s issue being number 1,000. And its legacy, overall, is a fine one—thanks to John W. Campbell, who ushered in the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

Another Milestone for Murania Press

I’ve just finished looking at the monthly sales report for May and am happy to report that, as of last month, more than 1,000 copies of The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction have now been sold. That’s not bad for a small-press “niche” product released a year and a half ago with no significant advertising or promotional effort.

Sales of the Guide were quite strong for the first six months, then lagged for a little while only to pick up again last year for reasons unknown. Approximately 15 percent of the sold copies have gone to international buyers. As one would expect, most of those went to English-speaking countries—Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom—but quite a few have found their way to European Union and Pacific Rim companies as well.

Although I’ve personally sold hundreds of copies via the Murania Press site, wholesale customers, and pulp-collector conventions, the book’s availability on Amazon has played a big part in achieving this milestone, especially with regard to those international orders. (It certainly helps that the Guide to date has elicited nothing but five-star reviews there.)

I’m also been gratified to see the Guide to Pulp Fiction being used as a text in college courses (and not only because that results in individual orders of two dozen or more copies). It was always my hope that this tome—like its predecessor, The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Collecting Pulps—would become a trusted reference work as well as a hobbyist’s handbook. The community of pulp collectors might be dwindling as innumerable reprints and facsimile obviate the necessity of purchasing the vintage magazines for reading purposes, but with interest in the fiction growing slowly and steadily, the need for a reliable, comprehensive guide is arguably more pronounced than it ever was.

Having reached this milestone somewhat earlier than I expected, I’m now more eager to see the Guide reach a wider audience. Beginning today, I’m going to offer it at $19.95—two-thirds of its stated retail price—to first-time subscribers to Blood ‘n’ Thunder. You can take advantage of that deal here.

Copy #2,000, here we come!

Unfairly Dissed and Dismissed: FAMOUS FANTASTIC MYSTERIES

You see copies everywhere. At conventions for collectors of vintage pulps, practically every dealer has some among his stock. They appear on eBay in vast quantities; many weeks you can find multiple listings of the same issue. They even pop up in places you rarely find old fiction magazines anymore: garage sales, antique stores, flea markets. No doubt about it, as vintage pulps go, Famous Fantastic Mysteries is darn near ubiquitous. And it’s this omnipresence that prevents today’s science-fiction fans and collectors from taking the magazine as seriously as it deserves.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries was launched in 1939 by the Munsey organization (then operating under the brand name “Red Star Publications”) to capitalize on the sudden boom in science-fiction pulps that in little more than a year had already spawned Planet Stories, Startling Stories, Science Fiction, Marvel Science Stories, and Dynamic Science Stories. The editorship of FFM was entrusted to 42-year-old Mary Gnaedinger, a long-time Munsey staffer. As the once-mighty company had fallen on hard times and was struggling to hold market share, Gnaedinger was instructed to fill the new pulp with old stories—fantasy, horror, “scientific romance,” and lost-race adventure—culled from early issues of such venerable Munsey titles as The Argosy, The Cavalier, and (most prominently) The All-Story and its successor, All-Story Weekly. Only the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs were off-limits to her; ERB had cannily retained reprint rights to his imaginative adventure yarns.

FFM‘s first issue (September-October 1939) featured seven complete stories, including two fan favorites: A. Merritt’s “The Moon Pool”and Ray Cummings’ “The Girl in the Golden Atom.” The second issue began Merritt’s novel-length sequel, “The Conquest of the Moon Pool,” which was serialized over six issues.

In fairly short order Gnaedinger reprinted well-remembered yarns by some of All-Story‘s best-known contributors of fantastic fiction: George Allan England, Garrett P. Serviss, Homer Eon Flint, Austin Hall, J. U. Giesy, Francis Stevens, Garret Smith, Ralph Milne Farley, Charles B. Stilson, and Edison T. Marshall, to name a few.

FFM introduced a new generation to these classic stories but also fired the enthusiasm of veteran pulp readers who deluged Gnaedinger with requests for dimly remembered stories initially published 10, 20, and even 30 years earlier. As many of these were book-length tales, she persuaded Munsey president William T. Dewart to launch a companion magazine, Fantastic Novels, in which to spotlight the longer stories. Eventually, FFM too ran novels complete in one issue, forcing Gnaedinger occasionally to cut excess wordage. This practice earned her the undying enmity of some SF purists, but in truth some of those stories benefit from the trims.

The sure-handedness of Mary Gnaedinger’s stewardship of FFM led Popular Publications president Harry Steeger to retain both her and the magazine when he bought the Munsey line from Dewart in late 1942. With a more generous editorial budget than she had been allotted previously, FFM‘s editor expanded the magazine’s horizons by purchasing reprint rights to works not originally published by Munsey. Within just a few years she had ushered into its pages such fantastic-fiction luminaries as Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, H. G. Wells, Robert W. Chambers, H. Rider Haggard, and William Hope Hodgson.

The first handful of FFM issues sported no cover artwork, instead merely listing authors and story titles. This approach, common to literary journals, hadn’t worked for editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman when he tried it on Adventure in 1927, and it didn’t work for Gnaedinger. Pulp-magazine buyers looked for exciting, colorful covers. She hired Virgil Finlay and Frank R. Paul, already known by SF fans for their work in Weird Tales and Amazing Stories respectively, to provide full-color cover painting as well as black-and-white interior illustrations. After moving to Popular Publications she also acquired the services of Lawrence Sterne Stevens and, later, Norman Saunders and Rafael de Soto.

In its last few years—the early Fifties—FFM continued to reprint top-notch fiction by Talbot Mundy, Sax Rohmer, H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, and more contemporary favorites such as Ray Bradbury, Theodore Sturgeon, and Robert E. Heinlein. The final issue (June 1953) even featured yarns by Ayn Rand and Franz Kafka alongside those of Howard and Bradbury!

I’m often asked by beginning collectors to recommend titles they should go after. I can’t think of a better one than Famous Fantastic Mysteries. The fiction is often first-rate, being reprints of classic stories, and the artwork is of similarly high quality. Moreover, as mentioned at the outset of this piece, copies are plentiful and therefore easily affordable. Not a single one of the 81 issues is rare, or even scarce. And with few exceptions each can be had, even in high grade, for less than the price of today’s average hard-cover book. I have some nice samples in my Collectibles For Sale section now.

Join Us for a New Installment of the ART’S REVIEWS Podcast!

Those of you who have 39 minutes to spare could do worse than listen to the May 22 installment of the popular podcast Art’s Reviews, on which yours truly was interviewed by host Art Sippo. Our wide-ranging conversation touched on various subjects near and dear to the hearts of pulp-fiction fans. I talked at some length about the recent Windy City Pulp and Paperback Convention and plugged the upcoming PulpFest. We also discussed the current state of the pulp-collecting hobby. And, of course, I described in considerable detail the new triple-sized issue of Blood ‘n’ Thunder (which, by the way, bids fair to establish a new record for single-copy sales) and soon-to-be-released volumes in Murania’s Classic Pulp Reprints series.

Art’s Reviews began last year as a continuation of the long-running Book Cave podcast started by Ric Croxton. For the last several years I’ve appeared on Cave ‘casts to promote PulpFest and Murania Press, and it’s always been a pleasurable experience. Art often joined Ric in conducting Book Cave interviews of writers, artists, publishers, collectors, and convention organizers, so he’s an old hand at the podcast game.

You can listen to our most recent conversation here….

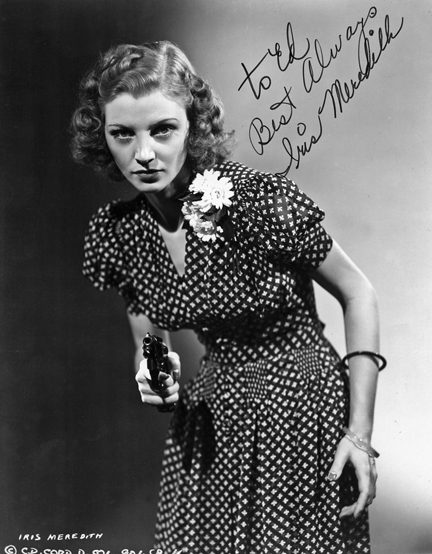

Birthday Girl: Iris Meredith

One of the most popular and frequently commented upon articles in Blood ‘n’ Thunder history is “My Dinner with Nita,” my tribute to Iris Meredith, the lovely actress who played pulp-fiction heroine Nita Van Sloan in a 1938 Columbia serial, The Spider’s Web. It first ran in issue #15 (Summer 2006) and was later reprinted in Blood ‘n’ Thunder’s Cliffhanger Classics. More recently it appeared as an interstitial piece in one of Anthony Tollin’s Spider pulp-reprint volumes. Since Iris was born exactly one hundred years ago today, I’m giving it some additional exposure: below you’ll find the complete text of “My Dinner with Nita.” I hope you enjoy it….

In the summer of 1976, I had an experience most serial fans could only dream of. I actually met, interviewed, and broke bread with the Spider’s paramour, Nita Van Sloan!

Not the real Nita, of course. That would have been impossible, because there wasn’t any real Nita. No, I attended a dinner with the reel Nita, the beautiful actress who played opposite Warren Hull in The Spider’s Web (1938), first of two fast-action Spider chapter plays made and released by Columbia Pictures.

Her name was Iris Meredith, and she had come to Nashville, Tennessee as a guest of the Fifth Annual Western Film Fair, a movie-buff confab sponsored by Western Film Collector magazine. Over the course of this four-day convention, some 160 feature-length films and a couple dozen serials—among them The Spider’s Web—unspooled in six makeshift screening rooms outfitted with 16mm projectors manned by bleary-eyed collectors. Movie showings began at 10 a.m. every day and continued until the wee hours of the next morning. The hucksters room included well over a hundred tables, some of them covered with boxes full of vintage-movie memorabilia, others sagging beneath the weight of film cans containing 16mm prints. Film Fair attendees could either screen themselves blind or spend themselves poor. Some did both.

Much-needed diversions were provided by panel discussions (in which the many guest stars reminisced about filmmaking in the Good Old Days) and the Saturday-night awards banquet, when actors long forgotten by the public at large accepted handsome plaques and standing ovations from True Believers who still cherished the Saturday-matinee movies of their youth.

I had already attended several such events and would likely have returned to Nashville even if Iris Meredith hadn’t been among the dozen or so performers invited to this year’s convention. But her presence was the icing on the cake for me. To think I’d be meeting the silver screen’s one true Nita Van Sloan! (Those of us who had seen both Spider serials rarely spoke of The Other, that brassy, garish floozy so obviously miscast in the 1941 sequel, The Spider Returns. As far as we were concerned, Iris Meredith was Nita. Period.)

Born on June 3, 1915 in Sioux City, Iowa, Iris Shunn didn’t have an easy childhood. By the time she was 10, her family had moved twice, first to Minnesota and then to southern California. By the time she was 13, both parents had died, leaving her to support three younger siblings with a Depression on the way. She attended school in the morning and toiled as a theater cashier in the afternoon and evening. Legend has it that Iris was discovered by a talent scout while working at the Loew’s theater in downtown Los Angeles. Still just a teenager—albeit a beautiful one—she briefly joined the fabled Goldwyn Girls and first appeared on screen with them in a 1933 Eddie Cantor vehicle, Roman Scandals.

Iris worked as a chorus girl in several movie musicals before landing her first substantial part: an ingénue role in The Cowboy Star (1936), a better-than-average “B” Western in which she played opposite Charles Starrett for the first time. (This film was the first in which she received on-screen billing, and for it she assumed the Meredith surname.) Starrett, scion of a wealthy northeastern family, had taken up acting while attending Dartmouth College. He never really caught on with adult moviegoers and in 1935 began starring in low-budget horse operas released by Columbia. He spent 17 consecutive years making Westerns for that studio, appearing exclusively as The Durango Kid from 1944 to 1952.

When Iris landed a Columbia contract, she was initially assigned to the unit cranking out Charlie’s pictures, and she co-starred with him in some 19 Westerns released between 1937 and 1940. The Starrett vehicles of this period maintained a fairly high standard, but their strict adherence to formula made one virtually indistinguishable from another. The Sons of the Pioneers, a Western-music group to which Roy Rogers once belonged, worked with Charlie and Iris in every picture. The supporting casts nearly always included Dick Curtis as the principal heavy and silent-screen veteran Edward Le Saint as either Starrett’s or Meredith’s father. Even the bit players were the same from picture to picture, and they almost always wore the same clothes. For that matter, so did Iris: She generally showed up in an ensemble consisting of plaid shirt with vest and split skirt.

Iris lobbied for parts in better movies but rarely escaped confinement in the Western and serial unit headed by producer Jack Fier. When she did, it was only temporarily and usually in a thankless role. In late 1940, after appearing in 22 Westerns and three serials, she left Columbia. For the next couple years Iris freelanced, finding it difficult to land roles outside of Hollywood’s Poverty Row. By 1943 she had married director Abby Berlin, himself a Columbia contractee; shortly thereafter she had a daughter and settled into domestic life.

Unlike some of her contemporaries, Iris never attempted a comeback when television series production created new opportunities for technicians and performers used to working at top speed on short budgets. She never dreamed that people still remembered her fondly, or that she had won new fans thanks to TV reruns of her old movies and the proliferation of 16mm dupe prints of the old Westerns. By the mid Seventies, however, the word was out. The “B”-Western stars, starlets, and supporting players were very much in demand at nostalgia-oriented film festivals, and Iris eventually accepted an invitation to appear at one such event.

Of course, those of us who attended that 1976 Western Film Fair had no way of knowing what hell Iris Meredith had been through. Some ten years earlier she had been diagnosed with oral cancer. She endured 14 operations, surrendering part of jaw and tongue in her fight against the disease. None of us expects our film favorites to withstand indefinitely the ravages of time, but we weren’t fully prepared for the severely disfigured, prematurely aged woman who courageously greeted her fans.

However shocked Film Fair attendees may have been, they never let on. Iris bravely met and talked with all of us, laboring mightily to make herself understood. Losing part of her tongue made it impossible to clearly articulate certain words, and her slurred speech was reminiscent of someone who’d had way too much to drink.

But ultimately this didn’t matter to us, and our outpouring of love plainly lifted her spirits. As the convention progressed Iris seemed demonstrably happier; by the second or third day one could see a twinkle in her rheumy eyes. Initially reluctant to speak, she pushed herself to engage fully with fans who approached her with questions as well as stills and lobby cards for her to sign.

She was accompanied by her grown daughter, who occasionally sat with her mom when Iris elected to watch one of her old movies. About halfway through a screening of The Spider’s Web—all 15 chapters in one marathon session, interrupted only by the projectionist’s reel changes—the daughter excused herself, leaving Iris alone. The screening rooms were sparsely attended at that moment; my recollection is that another guest-star panel was just getting underway. Only a dozen or so people remained to see the Spider battle his arch-foe, the Octopus, to a standstill.

A few rows behind and to the right of Iris, I stared at the erstwhile actress as the next episode began. She sat very still and straight, apparently transfixed by the flickering image of a younger, beautiful version of herself. I couldn’t help but wonder what might be going through her mind. Having already seen the serial several times, I left after one more chapter to attend another screening. As I eased through the screening-room door I shot a glance back at her. She was still riveted by the adventures of Dick, Nita, and the others.

On the third day of the convention, I persuaded Iris to sit for an interview. We adjourned to a small meeting room down the hall from the massive ballroom that housed dealers and other stars. She briefly stiffened when I brought out my portable cassette recorder, but after a few seconds—just as I was about to stuff it back into my briefcase—she relaxed again. “What would you like to know?” she asked.

Naturally, I was most eager to hear whatever she had to say about The Spider’s Web. “You know,” she said, “a year ago I couldn’t have told you anything about it. But now that I’ve seen it again, little things come back to me.

“Those serials were very hard to do. With the Westerns, you worked for a week or two and then you had time off. But those damn serials went for four, or five, or six weeks at a time. And we worked very long days, sometimes 12 or 14 hours. So every night you came home exhausted. It was all we could do to remember our lines the next day. The directors had it bad because they had to keep track of everything, all those little things that happened in the chapters.”

I asked her what she remembered about her castmates.

“Well, of course, I knew Richard Fiske already. We worked together on some of the pictures I did with Charlie [Starrett]. Warren Hull was a dear. Between takes he was a great kidder. And he loved to sing. He had a lovely voice. But then we would get in front of the camera and he would get so serious and squint, you know, and start shooting at people.

“I remember we all thought it was funny that Kenny Duncan was playing this Hindu [Ram Singh]. He was Canadian! And they gave him some of the craziest lines to say.” (I imagined Iris referred to Ram Singh’s snarling threats, like my favorite: “Dog with a pig’s face! If I had my knife, I’d carve my name in your heart!”)

“The other thing I enjoyed was that I got to wear nice clothes. I only had a few changes of wardrobe, but it was so much fun to wear nice dresses after doing all those Westerns in that damn split skirt. And of course, in the Spider film I didn’t have to deal with horses.”

Iris insisted, as had so many serial actors before and since, that she barely remembered making the chapter plays. “Really, we were rushing around so much we didn’t know half the time whether we were coming or going. The scripts were as thick as telephone books and every night I only memorized as many lines as I needed for the next day. We didn’t shoot the chapters separately, it was all done according to where on the back lot we were scheduled to be on any given day. Or on which set; we did many scenes on sets that had been built for other movies. I still wonder how the production managers kept things straight [during the making of a serial].”

She did, however, have specific memories of Overland with Kit Carson, the 1939 serial she did with newly minted cowboy star “Wild Bill” Elliott. “We went to Utah to shoot most of it,” she told me. Then she tried to pronounce the name of the town where the company stayed while on location, but I couldn’t understand what she was trying to say. Finally she scribbled the name on my note pad: “Kanab.” Several Westerns were made in and around that community, which the town fathers hoped would attract Hollywood producers in greater numbers. A Western street was built in the area to make Kanab a more appealing location for filmmakers; Overland with Kit Carson was the first production to utilize it.

Iris was fond of her Kit Carson co-star, with whom she also made three feature films. “Bill Elliott took his work very seriously,” she said. “The first picture I made with him, he wasn’t much of a rider yet. But he always practiced between takes. He got to be very good at it. And you know how he wore his guns, backward in the holsters? Well, he spent hours practicing a quick draw with those guns. I really admired him for working so hard to be convincing.”

She also had kind words for Ed Le Saint, another member of the Starrett stock company. “He was such a dear man. Very kind to me. But, you know, he was so old! I could never understand why they cast such an old man to play my father. Really, he was old enough to be my grandfather.”

By this time Iris seemed to be enjoying herself. She was no longer self conscious about the tape recorder, or about the effort it took to pronounce certain words. But I inadvertently brought our chat to an awkward halt with my next question:

“In 1940 you did your last serial, The Green Archer, for one of your Spider’s Web directors, James W. Horne. What do you remember about that film?”

Her face clouded and the spark went out of her eyes. She seemed more than a little sad as she quietly replied: “I don’t want to talk about that film. Please don’t ask me about it.”

I was stunned. What on earth could have happened during the making of that serial to elicit such a reaction? Fortunately, Green Archer was the last film about which I’d wanted to ask, and with nothing else to say I cleared my throat nervously and mumbled, “Well, I think we’re pretty much covered everything.” I thanked her, she thanked me, and as I got up from the table I could see several dozen fans milling outside in the hall, waiting for a chance to say hello and get her autograph.

That night at the banquet, following the typical rubber-chicken dinner, Iris Meredith was one of a dozen people presented with the inscribed plaque traditionally given to Western Film Fair guest stars. As she made her way to the podium, every person in the ballroom rose to give her a lengthy standing ovation. It was our way of honoring her for the courage and grace she had exhibited during the show. The room fairly crackled with electricity. Even from where I was, some ten feet from the dais, I could see her eyes welling up with tears. When the applause died down, she said just two words: “Thank you.” Then, as it swelled again, she took her seat and stared intently at her award, as if embarrassed to make eye contact with her adoring fans.

Subsequently Iris Meredith attended another film festival, but she never became a regular on the “nostalgia circuit,” as did some of her contemporaries. She continued her struggle with cancer, but the disease eventually overtook her. Not yet 65 years old, Iris died on January 22, 1980.

In 40 years of convention-going, I’ve met dozens of the actors, writers, directors, and stuntmen who worked on my favorite serials, Westerns, and “B” movies. I’ve enjoyed my encounters with all but two or three of them. But none ever affected me quite the way Iris Meredith did. It’s difficult to explain, but even now, decades later, I get a little thrill whenever I revisit The Spider’s Web and gaze at the optical player credits—you know, those glimpses of the principal actors with their names splashed across the bottom of the frame. Iris always stands there, clad in Nita Van Sloan’s flying togs, smiling sweetly and placidly even though she will shortly find herself menaced yet again by the minions of the Octopus.

In those moments, I like to pretend she’s smiling at me.

Underway: 2015 Memorial Day Sale!

Our last two Memorial Day sales were quite successful, so we’ve decided to try a third for this year. If you’ve been holding back on buying our recent releases, here’s your chance to pick them up at a discounted rate: Between now and 11:59 p.m. on Monday, May 25th, all Murania Press titles are available at 20 percent off cover price, with shipping included for purchasers in the United States.

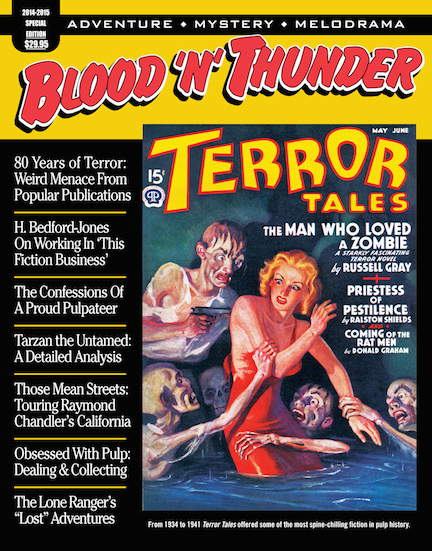

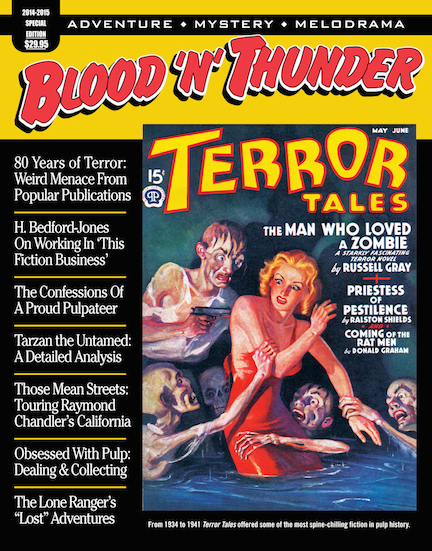

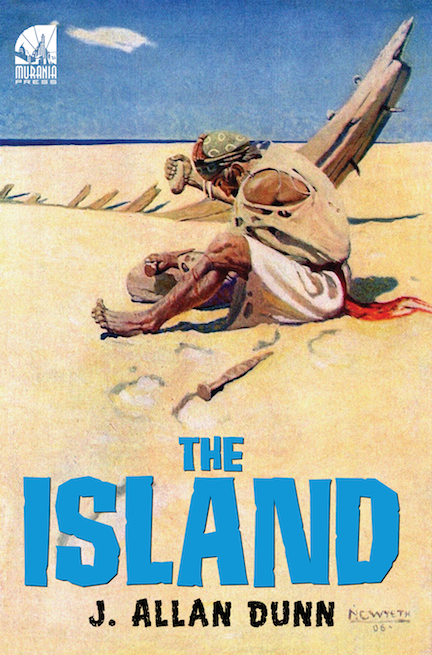

If, for example, you’re interested in the triple-sized Blood ‘n’ Thunder 2014-15 Special Edition (pictured below), you can pick it up this weekend for $23.95 instead of the usual $29.95. J. Allan Dunn’s The Island, Volume Five in our Classic Pulp Reprints series, can be had for $15.95 as opposed to $19.95.

Did you miss out on the award-nominated Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders, the first of our two volumes on silent-era movie serials? That, too, is temporarily available at $23.95, down from $29.95. Ditto for the best-selling book in our catalog, The Blood ‘n’ Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction. And if you’ve missed recent back issues of Blood ‘n’ Thunder itself, you can grab them for $10.00 each, postage included, rather than $12.50.

I must stress, though, that the free shipping extends to domestic U.S. customers only. We pay considerably more for books shipped internationally (including to Canada and Mexico) and, regrettably, must pass along those additional costs. Our average charge for sending a single item to foreign buyers is $6.99, but the good news is that the increase in shipping does not go up dramatically for multiple books. So by purchasing two or three at a time during one of our sales, international customers will find their postage fees largely absorbed by saving 20 percent off each item. If you’re buying from another country, please first send us an e-mail letting us know which books you want. After calculating the cost of shipping we’ll get back to you with a Paypal invoice for the total amount.

So while you’re waiting for the grill to heat up or those cookout guests to arrive, take a look at our books and magazines. If you’re a fan of pulp fiction, vintage movies and radio dramas, we guarantee you’ll find something of interest. Maybe several somethings. Happy hunting, and happy Memorial Day!

May 19: A 2nd Tarzan-Related Birthday

Earlier today I posted a birthday tribute to Herman Brix, a former screen Tarzan. But he wasn’t the only person with a connection to the Ape Man born on May 19th. The screen’s fifth and last silent-era Jane, Natalie Kingston, shared the same birthday and is likewise deserving of recognition here.

Born in 1905 as Natalie Ringstrom, this Golden State native showed traces of her mixed lineage, having both Spanish and Hungarian ancestors. Dark-eyed, dark-haired, and olive-skinned, Natalie grew up in the San Francisco Bay area. While still a teenager she began performing professionally as a dancer, briefly hoofing on Broadway. Natalie was just 18 when, having returned to California, she became one of Mack Sennett’s fabled Bathing Beauties and secured roles in his comedies starring Harry Langdon, among others.

In 1926, now billed as Natalie Kingston, she supported top comics Eddie Cantor in Kid Boots and Raymond Griffith in Wet Paint. Frequently cast as a fiery Latina, she occasionally played dramatic roles and was said to be particularly effective in a 1927 Ronald Colman vehicle, The Night of Love. Kingston also drew supporting roles in such popular late silent films as Howard Hawks’ A Girl in Every Port and Frank Borzage’s Street Angel.

In some of her early screen appearances Natalie looked a tad plump, but by 1928 she had slimmed down considerably. Lithe and leggy, the erstwhile chorus girl had never looked better when she was cast to play “Mary Trevor” in that year’s Tarzan the Mighty, a Universal chapter play scheduled for release in the fall.

The serial, supposedly based on the sixth book in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ long-running series, Jungle Tales of Tarzan, was actually filmed from an original screenplay. Kingston’s character had no counterpart in ERB’s collection of short stories, but she looked quite fetching in her abbreviated animal-skin garb. Champion gymnast and body-building enthusiast Frank Merrill, who had doubled Elmo Lincoln in The Adventures of Tarzan (1921), made a convincing Ape Man and bore at least a glancing resemblance to the Tarzan depicted in some of J. Allen St. John’s cover paintings.

The early episodes of Tarzan the Mighty were released while the serial was in the latter days of principal photography. Enthusiastic exhibitor reaction and the accompanying increase in bookings persuaded Universal to extend the film from 12 to 15 installments, thereby guaranteeing additional revenue inasmuch as serials were rented by the chapter. It was Universal’s highest-grossing production of the year.

The principal players—Merrill, Kingston, and villain Al Ferguson—were reunited the following year for the absurdly titled Tarzan the Tiger, a reasonably faithful adaptation of ERB’s Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar. This time around Natalie played Jane, who during the course of the story was menaced by Arab slave traders and Opar’s Queen La (played by the exotically beautiful Mademoiselle Kithnou). She screened to good advantage in a tasteful nude swimming scene. While successful, Tarzan the Tiger was not the box-office sensation that its predecessor had been, and the Ape Man’s screen career lay dormant for several years before being revived with M-G-M’s first Tarzan opus starring Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan.

Kingston had the female lead in one other Universal serial, The Pirate of Panama (also 1929), an adaptation of William MacLeod Raine’s adventure novel about modern-day treasure hunters. In a shameless bid to capitalize on her physical assets the script kept Natalie’s character clad in shredded garments for much of the footage, if production stills are to be believed. The chapter play itself is lost, as is Tarzan the Mighty.

Although Kingston had a perfectly acceptable voice and delivered dialogue convincingly, she failed to gain much of a foothold in talking pictures and worked in a handful of minor films before retiring from the screen in 1933, still in her twenties. Natalie fared better than many of her peers, however. She invested her money in real estate and attended law school to obtain the legal expertise required to successfully manage her holdings. She also enjoyed a long and stable marriage to one George Andersch, whom she wed shortly before beginning work on Tarzan the Mighty; their union ended with his death in 1960.

Natalie Kingston died in 1991 at her home in Los Angeles, just a couple months shy of her 86th birthday. Her brief tenure as the silver screen’s Jane would likely be totally forgotten had not a resourceful film pirate gained access to the only surviving 35mm print of Tarzan the Tiger in the mid 1980s. This gent made a good-quality video transfer from the deteriorating material and circulated VHS copies to selected collectors before selling sub-masters to grey-market video distributors a few years later. Thanks to him, Tarzan fans have developed an appreciation for the silent era’s sexiest Jane.

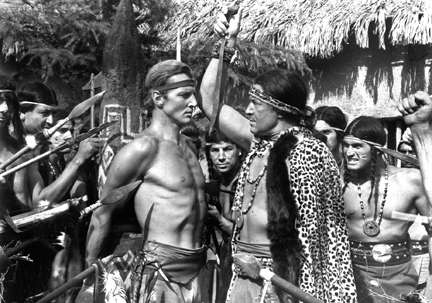

Birthday Boy: Tarzan of the Movies! (Well, ONE of them, anyway.)

On May 19, 1906 Olympic athlete-turned-actor Herman Brix—also known as Bruce Bennett, the adopted name he used for most of his professional life—was born in Tacoma, Washington. Most film fans probably remember Bennett for his roles in such classic “A” movies as Mildred Pierce (1945), The Man I Love (1947, his personal favorite), and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). Serial aficionados, however, revere the classic chapter plays in which he starred or co-starred as Brix: The New Adventures of Tarzan (1935), Shadow of Chinatown (1936), The Lone Ranger, The Fighting Devil Dogs, Hawk of the Wilderness (all 1938), and Daredevils of the Red Circle (1939).

I was supposed to visit and interview Brix in October 2002, at the tail end of a week-long stay in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, he got food poisoning the day before our scheduled visit and, unable to postpone my flight back east, I missed my chance. However, I prepared a list of questions and gave them to the friend who had offered to videotape the event; subsequently he conducted the interview for me, getting nearly two hours of footage of the 96-year-old actor.

I was primarily interested in writing the definitive article on New Adventures of Tarzan, and my questions elicited many then-unreported facts about the making of that 1935 serial. The article first appeared in Blood ‘n’ Thunder #5 (Summer 2003, long out of print) and was later included in Blood ‘n’ Thunder’s Cliffhanger Classics. For the Summer 2006 all-serial issue of BnT (also out of print) I distilled Brix’s few comments on his other serials into a brief article titled “Happy Hundredth, Herman!”, a reference to his recent centennial. To celebrate what would be the star’s 109th birthday I reprint those comments below.

On Shadow of Chinatown, his second serial and first film after playing Tarzan: I was taken by my agent to see [the serial’s producer] Sam Katzman, who wanted a leading man to play opposite Bela Lugosi. He hired me right away. I don’t remember waiting to be told I had gotten the part. Now, Bela was paid a considerable sum of money—I couldn’t tell you exactly how much—and he was on the set for one and a half days, total. That’s it. Shot all his scenes for a 15-chapter serial in one and a half days. (Editor’s Note: We find this very difficult to believe, given the amount of footage Lugosi has in Shadow. We’re more inclined to believe that he only worked a day and a half with Brix, who was in most scenes and therefore needed to be around for the entire shooting schedule.) That film was made in the days just before the Screen Actors Guild [instituted regulations governing overtime pay for actors]. Several times, I worked 12-hour, 14-hour days and just slept on a cot in the back of the studio. I wouldn’t go home for two or three days at a stretch.

[Director] Bob Hill was a very enthusiastic and humanitarian man, but he had a helluva job getting these things out on time. I liked him, but the quality of his pictures [for Katzman] was catch-as-catch-can. The direction was along the lines of, “You walk from here to here, you jump off that bridge there . . . .”

Bela was a nice guy. He and his wife had my wife and I out to his place for dinner one night when we finished shooting early. He told me he couldn’t understand how I could do all the things I did, the physical stuff as well as the acting, on that kind of schedule. “All those scenes in one day!” He was very professional, but I thought he had a strange sort of idea of acting. He learned all the lines, but he said them in his certain way and that was it. Frankly, I never understood why people wanted to see him [in movies]. But he had that peculiar quality of mystery about him that made him good for that kind of part.

Sam Katzman . . . well, at that phase of his career he gave the impression of being just a happy-go-lucky guy who hoped everything would turn out all right. But, boy, he sure watched the pennies. If he could save a few hundred dollars by having two crews work 12-hour shifts instead of paying one crew overtime, that’s the way he would do it. He was pretty clever at figuring out the most economical way of doing a picture.

On making his first serial for Republic, The Lone Ranger: That was a lot of fun. We shot most of the exteriors up in Lone Pine. We did lots of shots riding back and forth, here and there, with those mountains in the background. I remember they assigned me a horse named Blackjack. Now, he had a tough mouth. You really had to jerk the reins back hard to get him to respond. One day I was doing an insert shot, a running insert, and Blackjack got the bit in his teeth and wouldn’t stop. He jumped up on top of a boulder—I swear, it looked as big as a house to me—and I fell off backward, and he fell down as well. And that was the last day I rode Blackjack.

On making The Fighting Devil Dogs with his Lone Ranger co-star, Lee Powell, and director William Witney, who shared the megaphone with John English: I liked Lee a lot. We got to be pretty good friends and we did another serial together after The Lone Ranger. It was The Fighting Devil Dogs. We played Marines. I don’t remember too much about it, except that it had a lot of stock shots. The scenes were built around stock footage. But Lee and I had a lot of fun with it. There was a lot of action, a lot of fighting, as I recall. But, you know, when you’re young and active and in good health, you do the damnedest things that you otherwise wouldn’t do. During World War II, Lee was called up and went overseas. He was shot down not long after he got there. I was very unhappy to hear that he had died. I remember Billy Witney being an energetic, clever young director. On the set, he acted like, “Alright, I don’t care, do it that way.” But he always knew what he was doing. And everybody felt that way [about him].

Between scenes of THE LONE RANGER: Brix, behind the mask, with co-director Bill Witney and leading lady Lynn Roberts.

On making his only solo starring serial for Republic, Hawk of the Wilderness: That was fun to make. And I believe it was a fairly successful picture of that type for Republic. I can tell you what I remember most about that one. At the end of the shooting schedule, there were still a number of scenes—maybe 15 pages of script—that hadn’t been shot. Scenes with the Hawk doing things alone, running, climbing, and other things. This stuff hadn’t been shot when the production originally shut down. So [the producer] had me come back and we went up to the location, just me and a camera crew. Well, we shot one whole day, that night, and into the next day—without stopping. Now, by that time the SAG regulations were [being enforced], and I was on triple overtime. I got more money for those two long days and one night than I got for the whole film!

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net