EDitorial Comments

The Movie Serial’s Precursor: “10-20-30” Stage Melodrama

(Have you ever wondered from whence the motion-picture serial developed? Here’s an excerpt from my upcoming book, Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders, which explains the chapter play’s origin at some length.)

From its beginnings, the motion-picture serial reflected the influences of popular-priced stage melodrama and mass-market fiction, the latter delivered to thrill-hungry readers in cheaply produced woodpulp magazines. Chapter-play writers hewed closely to the well-established conventions of pulp periodicals and sensation-based theatrical productions because they hoped to attract the same consumers to which those mediums appealed: largely working-class folks, and a small but significant percentage of the middle class. The relatively short lengths and primitive storytelling techniques of nickelodeon-era motion pictures made inevitable a reliance on melodrama, with its simple narratives, broadly sketched situations, and clearly defined character types.

Stage melodrama emerged at the turn of the 19th century, but it took nearly a hundred years to evolve into the form from which early filmmakers drew plots, themes, and concepts. By then known as “10-20-30” (reflecting the prices asked by theaters specializing in this sort of fare), the thrill-charged stage melodrama flourished in small towns and big cities alike, playing mostly to uncritical, unsophisticated, and sometimes marginally literate spectators. Many successful shows of the type premiered in New York City, where they were known generically as “Third Avenue melodrama,” owing to the proliferation of 10-20-30 theaters along that particular thoroughfare.

The hallmark of 10-20-30 was sensationalism. Nineteenth-century melodrama is often identified with mustache-twirling, black-garbed villains of the “Curses, foiled again” stripe, badgering defenseless young women for overdue rent money, but 10-20-30 productions went far beyond eyeball-rolling malefactors and sobbing ingenues.

The average 10-20-30 story was presented in four acts and incorporated as many as 20 separate scenes, some lowering the curtain in the immediate aftermath of thrilling situations — not unlike the serial’s “cliffhanger” endings — calling for elaborate scenic effects. The climax of Joseph Arthur’s The Still Alarm (1890, and adapted to celluloid several times during the silent-movie era) boasted a race to the rescue in which real horses, hitched to a real fire engine, galloped on a treadmill (backed by a revolving cyclorama to create the illusion of speed) to the scene of a conflagration represented by smoke wafting across the stage from carefully hidden pots.

The heroine of Charles T. Dazey’s In Old Kentucky (1893), which also had several screen incarnations, was called upon to swing by rope across a deep chasm and rescue a racehorse from a burning stable. Ramsey Morris’s The Ninety and Nine (1902) depicted the passing of a locomotive through a forest fire, and Charles A. Tyler’s Through Fire and Water (1903) simulated the plunging of a canoe over a waterfall. Such effects required complicated sets and apparatus, and were occasionally achieved with astonishing verisimilitude. Both natural and unnatural disasters paraded nightly across the stages of 10-20-30 theaters.

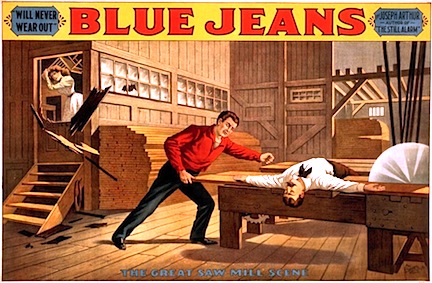

Perhaps the ne plus ultra of such thrills was the climactic sequence of Joseph Arthur’s Blue Jeans (1890), arguably the most influential 10-20-30 melodrama. Villainous Ben Boone (played by George Fawcett) lures hero Perry Bascom (Robert Hilliard) and wife June (Jennie Yeamans) to a lumber mill. The young woman is locked in a small office adjoining the plant, where her husband is knocked unconscious and placed on a conveyor belt atop a log being carried toward a whirling buzz saw. There was nothing phony about this scene — which worked on two levels, as explained by the Boston Evening Transcript’s Jeanette Leonard Gilder, writing as “Brunswick”:

The fourth and last act shows us the Buzz Saw going at full speed. To show that the saw is as real as the buzz, it is made to cut thick boards into lengths, and cold shivers pass over the audience as it settles itself down to enjoy what it thinks, I will not say hopes, may be a real tragedy. . . . With a fiendish smile upon his face, [villain Ben Boone] points to the buzz-saw, winks at the audience and places the unresisting form of Hilliard within a few feet of the cruel wheel. He is being drawn nearer and nearer his doom, and we expect every moment to see the buzz-saw do to the prostrate actor what King Solomon intended to do to the disputed baby, when [the heroine] June breaks through the door and grabs him away from certain death just before he is split in twain.

Not surprisingly, Blue Jeans was a huge hit — the gaslight-era equivalent of today’s “water cooler” TV programs. Fortunately, actor Hilliard escaped injury night after night, but the potential for disaster was there in every performance. (The buzz-saw bit became so firmly ingrained in memory that early serial writers and directors referred to any hazard-portraying chapter ending as “a Blue Jeans finish.”) Acting in 10-20-30 melodramas was not for the faint-hearted or weak-limbed: cast members were expected to do stunts such as wire-walking and rope-swinging in addition to trading poorly-pulled punches and making the occasional leap from a wood-flat scaffold painted to resemble a cliff.

(Part Two of this excerpt follows tomorrow. How could I cover this topic without giving you a “To Be Continued”?)

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net