EDitorial Comments

Hoppy birthday, William Boyd: Part 1

One hundred and seventeen years ago today, William Boyd was born in Hendrysburg, Ohio. When he was seven his family moved to Oklahoma, where Bill’s parents both died before he finished high school. Left to fend for himself, the strikingly handsome youth initially found work as a grocery-store clerk, then as a surveyor and oil-field worker. Bill married for the first time in 1917 and soon thereafter moved with his wife to Hollywood, California, where they hoped his pretty face would land him work in moving pictures. Happily for generations of Western fans, they were right.

In 1918 Bill made his screen debut as an unbilled extra in Cecil B. DeMille’s Old Wives for New. The already famous director championed young Boyd and over the next seven years gave him increasingly larger parts. Following Bill’s strong showing as the second male lead in The Road to Yesterday (1925), DeMille made him a full-fledged star in The Volga Boatman (1926) and gave him a pivotal role in the Biblical epic King of Kings (1927).

Boyd’s light, wavy hair and boyish good looks stood him in good stead throughout the silent era. He never reached the heights attained by such matinee idols as John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, or John Barrymore, but he achieved some prominence as a dependable leading man in moderate-budgeted films made by the DeMille-sponsored Producers Distributing Corporation and released by Pathé Exchanges, Inc.

The advent of talking pictures didn’t hurt Boyd’s career; his voice was perfectly suitable to the new medium. When Pathé was absorbed into the conglomerate that became RKO Radio Pictures, Bill maintained his star status for several years, although his films were relatively inexpensive “program pictures”—the type that could play either half of a double bill, according to theater size, location, and clientele. Disaster struck in 1933, when newspapers and wire services across the country ran a photo of him accompanying lurid accounts of a sex-and-booze scandal involving another actor named William Boyd. Although it was a plain case of mistaken identity, the ensuing kerfuffle stopped Bill’s career dead in its tracks. It didn’t help that he was thrice divorced and a big drinker himself. Some media outlets ran corrections, but the damage was already done. RKO dropped Boyd like a hot potato, and for the next two years he could only find work in Poverty Row cheapies that traded on his earlier fame.

In early 1935, independent producer Harry “Pop” Sherman acquired screen rights to the Hopalong Cassidy stories written by Clarence E. Mulford. He raised funds to make a series of six pictures and then cut a distribution deal with Adolph Zukor’s Paramount Pictures. There was one caveat: In the interest of facilitating the series’ marketing and promotion, Paramount insisted that Sherman cast a recognizable star—past or present—in the lead role.

Originally, Pop had planned to make his celluloid Cassidy the grizzled cowpuncher of Mulford’s later novels (which were serialized in the pulp magazine Short Stories prior to book publication by Doubleday), but Paramount’s demand forced him to change direction. Problem was, the major movie cowboys were getting more money than he could afford to pay.

Sherman was turned down by several actors before someone recommended he approach Bill Boyd, who was “at liberty” after having completed four low-budget melodramas for Poverty Row producer George Hirliman. Boyd was not a horse-opera star per se, but two of his most popular starring vehicles—The Last Frontier (1926) and The Painted Desert (1930)—had been epic Westerns.

Although Bill wasn’t especially fond of Westerns, he eagerly accepted Sherman’s offer of five thousand dollars per film with a six-picture guarantee. At the time, neither Boyd nor Sherman had any expectation that the Hopalong Cassidy series would extend beyond the half-dozen entries scheduled for Paramount release during the 1935-36 season. Happily for generations of Western fans, they were wrong.

More on birthday-boy Boyd and Hoppy tomorrow….

28 thoughts on “Hoppy birthday, William Boyd: Part 1”

Leave a Reply

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net

Great article about Hoppy. I will be looking forward to reading the rest.

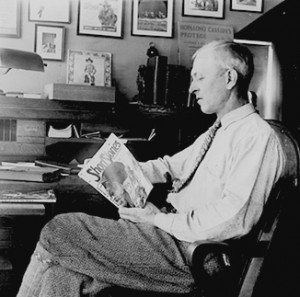

Nice info on Boyd, and the photo of Mulford with the copy of Short Stories is awesome! Jonathan

Jonathan, it’s hard to see because the picture is reproduced very small here, but there’s a copy of the May 1928 Frontier Stories on the desk in front of Mulford.