EDitorial Comments

Windy City Film Program: Day Two

Saturday

10:00 am — Donovan’s Brain (1953, United Artists, 83 minutes)

Adapted from Curt Siodmak’s “Donovan’s Brain” in Black Mask, September-November 1942.

Dr. Patrick Cory (Lew Ayres) and his colleague Dr. Frank Schratt (Gene Evans) are researching brain activity, performing experiments on monkeys in their remote laboratory. A plane crashes nearby and its mortally wounded passenger, crooked financier W. H. Donovan, brought to Cory’s lab because it’s closer than the nearest hospital. Cory is unable to save Donovan but removes and preserves the tycoon’s brain, which exhibits telepathic abilities and takes over the doctor’s mind. From beyond the grave Donovan exerts his malevolent influence over Cory, directing the physician to dispose of the millionaire’s enemies.

“Donovan’s Brain” was an odd choice for publication in the pulp magazine Black Mask, being neither a detective yarn nor a story that fit the classic definition of a mystery. Author Curt Siodmak felt the same way and admitted as much to me in 1998. “But,” he added, “it was a magazine sale, and in those days you wanted to serialize your stories in magazines before they came out as books. At least that’s what my agent told me.” Originally filmed in 1944 as The Lady and the Monster, Siodmak’s thriller was more faithfully adapted by Hugh Brooke and Felix Feist; the latter also directed. Neither version properly characterized Patrick Cory, whom Siodmak portrayed in the novel as cold-blooded, self-absorbed, and rather contemptuous—qualities that made him receptive to Donovan’s telepathic control. But this is a minor failing. Overall, Donovan’s Brain makes top-notch entertainment.

11:30 am — The Saint in London (1939, RKO Radio Pictures, 72 minutes)

Adapted from “The Million Pound Day” in Mystery Novels Magazine, Spring 1933.

Back in London after a long absence, Simon Templar (George Sanders), aka The Saint, learns that high-society gambler Bruno Lang (Henry Oscar) is involved in a plot to flood England with a million pounds’ worth of counterfeit currency. Before long the conspirators commit murder and Templar decides to take a hand. Aided by adventure-loving Penny Parker (Sally Gray) and American pickpocket Dugan (David Burns), The Saint races against time to ferret out the brains behind the counterfeiting ring. With his old nemesis, Scotland Yard Inspector Claud Teal (Gordon McLeod), in hot pursuit, that won’t be easy.

The third in RKO’s series of Saint films, London was the first actually produced in the United Kingdom. At that time British law required that American motion-picture companies doing business in England make a certain number of movies there. Although the film was scripted in Hollywood, all other aspects in production were handled overseas, with principal photography mostly taking place at the Rock Studios in Hertfordshire, north of London. George Sanders had settled in America but cheerfully returned to the city where he’d broken into show business as a chorus boy. The Saint in London lacks the verve of Hollywood-filmed entries but maintains fidelity to its source material.

01:00 pm — The Glass Key (1942, Paramount Pictures, )

Adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s “The Glass Key” in Black Mask, March-June 1930.

Tough political boss Paul Madvig (Brian Donlevy) forges an alliance with reform-minded Senator Ralph Henry (Moroni Olsen) and is smitten with the Senator’s daughter Janet (Veronica Lake). Madvig’s advisor and best friend Ed Beaumont knows that Janet loathes Paul and strings him along only to help her father secure reelection. Henry’s scapegrace son Taylor (Richard Denning), who has been dating Paul’s sister Opal (Bonita Granville), turns up dead and Madvig falls under suspicion. Ed has an idea that gangster Nick Varna (Joseph Calleia) may have engineered the murder to frame Paul, and he takes desperate chances to find out.

We included the 1935 adaptation of The Glass Key in our very first Windy City film program, back in 2002, and while that version has a lot to recommended it, this Stuart Heisler-directed remake is superior. Screenwriter Jonathan Latimer, writer of the highly regarded “Bill Crane” mysteries published by Doubleday’s Crime Club in the Thirties, builds on the 1935 script with additions from Hammett’s novel and some minor flourishes of his own devising. The casting is good, with standout performances from Calleia, Granville, and especially William Bendix as Nick Varna’s thuggish henchman Jeff. Theodor Sparkuhl’s shadowy photography anticipates the film noir style (still a few years off) and Archie Marshek’s film editing maintains perfect pacing. This one’s a real crackerjack. Based on its success, both critically and commercially, Latimer wrote an adaptation of Hammett’s Red Harvest. Sadly, that film wasn’t made.

02:30 pm — Street of Chance (1942, Paramount Pictures, 74 minutes)

Adapted from Cornell Woolrich’s “The Black Curtain” in Two Complete Detective Books, Spring 1942.

Mild-mannered Frank Thompson (Burgess Meredith) is grazed by something that falls from a skyscraper. Dazed, he staggers home to his wife Virginia (Louise Platt), who’s thrilled to have him back home: He’s been missing for a year. Frank realizes he’s suffering from amnesia and must recreate this chunk of his life. A woman named Ruth Dillon (Claire Trevor) assists him in trying to do so, but Frank suspects he must have done something horrible because a dark, sinister-looking man (Sheldon Leonard) pursues him relentlessly.

In one of my old film-history articles I called Street of Chance “the best ‘B’ movie ever made,” and while I’ve since seen other serious contenders for that honor, it’s certainly not a stretch to number this criminally little-known jewel among the best three or four film adaptations of a Cornell Woolrich story. And with more than two dozen works based on the author’s yarns made in Hollywood alone, that’s saying something. I must point out, though, that including it in a Windy City lineup is a bit of a cheat: “The Black Curtain” wasn’t written for the pulps, it was first published as one of Simon & Schuster’s Inner Sanctum novels and reprinted in Two Complete Detective Books a few months later. But this magnificent thriller bears all the hallmarks of Woolrich’s best rough-paper work, and since the movie version has only recently been released on home video—for the first time in any format and digitally restored from original 35mm film elements—I couldn’t resist scheduling it. Like the 1942 Glass Key it’s a forerunner of film noir, not only stylistically but thematically. Former film editor Jack Hively is not considered a particularly important or innovative director, but Street of Chance alone has earned him a place in cinema-history books. Saying any more would just be gilding the lily, so I’ll close with an exhortation: Don’t miss this one.

04:00 pm — Find the Blackmailer (1944, Warner Bros., 56 minutes)

Adapted from G. T. Fleming-Roberts’ “Blackmail with Feathers” in Detective Novels Magazine, August 1942.

Down-at-heel private detective D. L. Trees (Jerome Cowan) is hired by politician John Rhodes (Gene Lockhart) to locate a talking blackbird being used to blackmail him. The bird’s owner, a crooked gambler, taught it to squawk “Don’t kill me, Rhodes!” just before being murdered. The chief suspects include gangster Mitch Farrell (Bradley Page), lawyer Mark Harper (Robert Kent), and femme fatale Mona Vance (Faye Emerson). But there’s more to the mystery than a talking bird and some suspicious characters, as Trees learns the hard way.

Incredibly prolific pulpster G. T. Fleming-Roberts managed to sell only two of his hundreds of stories to Hollywood. Find the Blackmailer was first to reach the screen, and while even the most knowledgeable film buffs who have trouble recognizing the title, this breezy little “B” picture—not even an hour long—is equally offbeat and entertaining. It’s helped immeasurably by the performance of long-time character actor Cowan (you’ll remember him as Sam Spade’s murdered partner in the 1941 Maltese Falcon) in one of his few leading roles. The rest of the cast is good too, with minor player Marjorie Hoshelle registering strongly if her brief scenes as Trees’ long-suffering secretary. Director D. Ross Lederman, an old hand at fare of this type and budgetary class, keeps things moving at a good clip and injects as much comedy relief as the script permits.

Following auction — Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937, Republic Pictures, 54 minutes)

Adapted from William Colt MacDonald’s “Riders of the Whistling Skull” in Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, March 1934, and “Valley of the Scorpions” in Big-Book Western, November 1934.

The Three Mesquiteers—Stony Brooke (Bob Livingston), Tucson Smith (Ray Corrigan), and Lullaby Joslin (Max Terhune)—join an archaeological expedition searching for the lost city of Lukachukai, home to descendants of an ancient Indian murder cult known as the Sons of Anatazia. One of the scientists has just been murdered, and detective-story enthusiast Stony is eager to find the killer. While searching for the lost city’s landmark—a huge rock formation in the shape of a human skull—the expedition is menaced by raiders from the lost city. The Mesquiteers learn that the man behind these depredations is a member of their party, but acquiring that knowledge may have come too late to save them.

Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937), Republic’s fourth Three Mesquiteers opus, was the best to date. The screenplay by Oliver Drake and John Rathmell combined plot elements from two MacDonald novels, “Whistling Skull” and its successor, “Valley of the Scorpions” (published in hard covers as The Singing Scorpion). It offers a refreshing departure from horse-opera formula. There are no cattle rustlers, stagecoach robbers, crooked bankers, or dictatorial ranchers. No stampedes, no saloon brawls, no street duels at high noon. Instead there’s genuine mystery and steadily building suspense. The film is suffused with mystery and includes a dollop of horror to chill the blood. Competent but undistinguished director Mack V. Wright fails to fully exploit the script’s possibilities—it indicates a spooky atmosphere he never really develops—yet Riders succeeds primarily by virtue of its novelty. At 54 minutes it’s short and fast-moving . . . just what you’ll crave after a lengthy auction!

Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

The 2023 film program contains several obscurities, as usual, and we acknowledge this year’s 90thanniversary tribute to the 1933 hero-pulp explosion with a screening of George Pal’s Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze, a fan favorite not previously shown here. We’re also including remakes of popular pulp adaptations featured in early Windy City movie lineups. With adventure, drama, mystery, suspense, horror, Westerns, and science fiction all represented in the schedule, it’s our hope there will be something for everyone. As always, we invite you to take a periodic break from dealer-room shopping, get off your feet for a while, and enjoy one or more of these great films adapted from pulp-magazine stories.

Friday

12:00 pm — Burn, Witch, Burn (1962, Anglo-Amalgamated Pictures, released in the U.S. by American-International Pictures, 90 minutes)

Adapted from Fritz Leiber Jr.’s “Conjure Wife” in Unknown Worlds, April 1943.

College professor Norman Taylor (Peter Wyngarde) seems to be living a charmed life. Everything is going his way and he’s the odds-on favorite to be named department head, even though most of his colleagues have been teaching there much longer. When Norman learns his superstitious wife Tansy (Janet Blair) has been practicing witchcraft to ensure his good fortune, he insists she burn all the paraphernalia she’s used to craft the spells protecting him. And that’s when bad things starts happening to Norman. . . .

Leiber’s “Conjure Wife” had previously been filmed as Weird Woman (1944 Universal), a reasonably effective “B”-grade chiller that didn’t entirely do justice to the original story. Burn, Witch, Burn (released in England as Night of the Eagle) takes its own liberties with the source material but on balance is a more faithful adaptation. Wyngarde is a tad too arrogant to make Norman a wholly sympathetic figure, but Blair—who spent most of her film career in musicals and comedies—scores decisively as the apprehensive wife. The script by Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson is literate and well-constructed, and Sidney Hayers’ direction masterfully builds suspense that culminates in a genuinely shocking climax.

01:45 pm — Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975, Warner Bros., 100 minutes)

Adapted from Kenneth Robeson [Lester Dent]’s “The Man of Bronze” in Doc Savage Magazine, March 1933.

The year is 1936. Famed surgeon and adventurer Clark Savage Jr. (Ron Ely) and his five intrepid aides (William Lucking, Paul Gleason, Michael Miller, Darrell Zwirling, and Eldon Quick) travel to the South American country of Hidalgo in a bid to locate Doc’s father, who has disappeared in the jungle. Their mission is opposed by unscrupulous Captain Seas (Paul Wexler), who fears that the Bronze Man and his companions will beat him to a fortune of Incan gold said to be located in Hidalgo.

Loosely adapted from Lester Dent’s first Doc adventure, Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze was produced by George Pal, the erstwhile producer of animated cartoons who graduated to feature films in 1950 and turned out a slew of memorable fantasy, science fiction, and adventure movies. He gets screen credit for co-writing Doc’s script with Joseph Morheim, and while the two men successfully incorporated elements from several of the pulp novels, they undermined the effort by layering the yarn with “camp” touches that, sadly, were only enhanced by Michael Anderson’s tongue-in-cheek direction. Even so, there’s plenty to enjoy here, and former Tarzan Ron Ely makes an imposing Doc. A sequel was already in development when the original’s disappointing box-office returns forced Pal to cancel it.

03:30 pm — Under Eighteen (1932, Warner Bros., 79 minutes)

Adapted from Agnes Christine Johnson and Frank Mitchell Dazey’s “Sky Life” in Everybody’s Magazine, October 1929.

Young seamstress Margie Evans (Marian Marsh) lives in a crowded tenement flat with her parents, her sister, and her worthless brother-in-law. Discouraged by her lack of financial prospects, Margie yearns for better things and is reluctant to marry her hard-working boy friend, milk-truck driver Jimmie Slocum (Regis Toomey). A quirk of fate brings Margie in contact with millionaire Raymond Harding (Warren William), who has a not-entirely-deserved reputation as a cad. He takes an interest in the seamstress when she crashes a pool party at his New York penthouse.

Marian Marsh made a strong impression as the ingenue in two 1931 John Barrymore dramas for Warner Bros., Svengali and The Mad Genius, inspiring the studio to give her a big build-up and a star vehicle. Under Eighteen was that film, and it’s a sterling example of the type of motion picture in which Warners specialized during the early Depression years. No other Hollywood production entity was so adept at depicting life in the big city and portraying the disappointments and disillusionments of barely-employed working stiffs struggling to get by. Tenements in M-G-M or Paramount films were shabby but clean and tranquil; in Warner Bros. films they had men and women lolling on fire escapes or rooming-house stoops, kids playing in the streets, babies crying, street vendors speaking Yiddish, and so on. Under Eighteen is hardly the best of its type, and it failed to advance Marsh’s career as Warners had hoped. But it’s solidly entertaining and boasts some terrific performances, especially from the perennially underrated Warren William.

Following auction — Stagecoach War (1940, Paramount Pictures, 62 minutes)

Adapted from Harry F. Olmsted’s “War Along the Stage Trails” in Dime Western, July 1937.

Crusty old Jeff Chapman (J. Farrell MacDonald) needs new horses for the rag-tag stage line he’s been managing for years. He buys a small herd of mustangs from the Bar-20, which entrusts delivery of the mounts to top hands Hopalong Cassidy (William Boyd), Lucky Jenkins (Russell Hayden), and Speedy McGinnis (Britt Wood). Chapman’s competitor Neal Holt (Harvey Stephens) has a crush on the old man’s daughter Shirley (Julie Carter) but would happily drive her father out of business if he could. Complicating matters are the robberies being pulled by an outlaw band getting inside information from Holt’s foreman Twister Maxwell (Frank Lackteen).

When producer Harry Sherman in 1935 licensed screen rights to Hopalong Cassidy from author Clarence E. Mulford, he obtained two dozen novels for potential adaptation. It took less than five years to run through them, forcing Sherman to commission original screenplays and license Western stories from other writers. Stagecoach War was the first film in the long-running series to be based on a non-Hoppy yarn, Harry Olmsted’s “War Along the Stage Trails.” Scripter Norman Houston was tasked with grafting Hoppy and his pals onto Olmsted’s plot. Although this 30th series entry has a number of strong points—including an unexpectedly engaging group of bad guys and a good musical score—it also has several weaknesses, the most glaring being a weak ingenue in Julie Carter, for whom Lucky rather inexplicably falls hard.

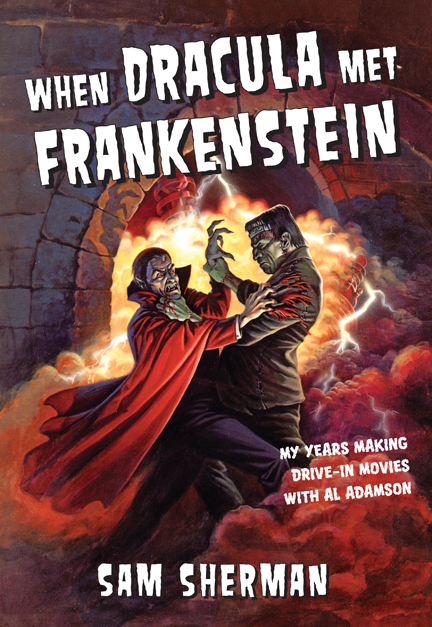

Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

Murania’s first book published since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic also happens to be the first not written or edited by me. But it’s an excellent addition to our line and I’m delighted to announce its availability.

In 1968 two ambitious young filmmakers, working on a shoestring, made a movie about a ruthless motorcycle gang. Titled Satan’s Sadists, it became the initial release of their new company, Independent-International Pictures, and was wildly profitable. Over the next two decades Sam Sherman and Al Adamson collaborated on a succession of low-budget films that attracted moviegoers to drive-ins and hardtop theaters alike. They exploited all the hot trends—horror, sci-fi, biker films, martial arts, sexploitation, blaxploitation—and marketed their product with dynamic, occasionally lurid campaigns. IIP used limited resources wisely and cast its films with a mix of talented young performers and former stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Along the way Sam and Al encountered many of the industry’s most colorful characters, both behind and in front of the camera.

Their films included some of the most memorable—and most memorably awful—attractions that played in urban entertainment districts such as New York City’s “The Deuce” (42nd Street to the uninitiated) and on drive-in screens all across the country: Girls for Rent, Women for Sale, Females for Hire, Mean Mother, Dynamite Brothers, Naughty Stewardesses, Blazing Stewardesses, Brain of Blood, Brain of Ghastly Horror, Horror of the Blood Monsters, and of course the legendary Dracula vs. Frankenstein. And those are only some of the jewels in IIP’s celluloid crown: the company’s holdings run to several hundred films, a good number of them foreign exploitation films that IIP imported and released domestically under new titles.

In this book Sam Sherman revisits those halcyon days and reveals the behind-the-scenes story of IIP’s rise and fall. But When Dracula Met Frankenstein is more than the chronicle of one company: It paints a vivid picture of the entire drive-in era and the feisty independent producers and distributors who comprised the lower strata of the motion-picture industry. Accompanied by nearly 250 images—posters, scene stills, and candid on-set photos (many never before published)—Sam’s memoir is a must-have for casual fans and film historians alike. Its 378 pages are chock full of behind-the-scenes anecdotes that not only put to rest the most outrageous rumors about IIP but also provide valuable insights about the under-documented underbelly of the movie trade.

Full disclosure: Sam Sherman and I have been friends for nearly a half century. Even before I knew him, I knew who he was, because as a grade-school kid and budding film buff I religiously followed Screen Thrills Illustrated, the magazine he co-edited with the late Bob Price for Famous Monsters publisher Jim Warren. Friendship notwithstanding, though, I’d have been delighted to publish When Dracula Met Frankenstein. It’s a terrific reminder of those years I spent on The Deuce, seeing obscure horror and exploitation films that never made it to the multiplexes in my suburban New Jersey neighborhood.

Sadly, Al Adamson died in a manner befitting any number of characters in IIP movies: He was brutally murdered by a larcenous contractor renovating one of his houses, his corpse entombed in the concrete bed of a hot tub. But in this book Sam pays more than ample tribute to his resourceful, hard-working partner, whom he calls “the brother I never had.”

You can order When Dracula Met Frankenstein now by clicking here.

Collectibles Section Update

We’ve recently sold many of the items listed in our Collectibles For Sale section, and as a first step toward replenishing our supply we’ve just added 15 or so items, most of them pulps. You’ll find a number of very desirable items and a couple of true rarities in this update.

Below are just a few of the new additions….

Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Last night I learned that long-time friend and fellow pulp collector Mark Halegua passed away on March 18th at the age of 66. After he failed to respond to multiple e-mails and phone calls over a period of several days, a mutual friend called the NYPD and asked them to visit Mark at his apartment in the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens. The police first performed an on-line check, which revealed that Mark had passed away from unnamed “medical complications” and that his next of kin had been notified.

I was momentarily shocked but not altogether surprised to learn of his death. Mark had been in poor health for some time. He was already diabetic when he suffered a serious heart attack last August. He spent several months in hospital and then in a rehab facility; during this time he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure and put on diuretics to flush excess fluid out of his body. Eventually he developed kidney disease and was undergoing dialysis three times weekly. I don’t know if Mark contracted Covid-19, but his underlying conditions certainly put him in the high-risk category. He would have been among patients least likely to survive the virus.

Those of you who frequently attend pulp conventions would remember Mark as a regular attendee. More often than not he could be found in the dealers room, selling everything from vintage magazines to T-shirts adorned with pulp covers to CDs loaded with cover scans. He also peddled these wares from his Pulps 1st website. Mark was a big guy, hard to miss, with a ready smile and a hearty laugh that reverberated in even the biggest space.

Back in the early Seventies I used to see him at a large comic-book convention staged in New York City every July 4th weekend. He was just a guy I passed in the dealers-room aisles; I knew him by face but not by name. Oddly, I met his brother Richie more than a decade before I got to know Mark. For many years Rich Halegua was a prominent dealer in original comic art and I was one of his customers. Got many good pieces from him.

At the 1997 Pulpcon in Bowling Green, Ohio, I recognized Mark from the comic-book conventions and introduced myself. During our first brief conversation I learned he was a fan and collector of the “Thrilling Group” pulps edited by Leo Margulies and published by Ned Pines. He was compiling complete sets of The Phantom Detective, Black Book Detective (with his favorite character, the Black Bat), and Captain Future, among others. He liked hero pulps in general and also had a fondness for science fiction.

I can’t honestly say Mark and I became close friends, but we interacted every year at Pulpcon and I occasionally ran into him at a small monthly New York gathering of comic-book collectors. My own interest in comics had long since dissipated, but a few of that show’s regular dealers also carried pulps. One day I remember approaching a merchant who was patiently listening to Mark chide him for charging too much for his pulp magazines. The guy easily could have snapped, “If you don’t like my prices, get the hell away from my table.” To his credit, though, he took Mark’s tongue-lashing with equanimity. After finishing the tirade Mark strode off, waves of righteous indignation rippling in his wake as he clomped away. Years later I teased him about that event. “But,” he replied, “his prices were too high.” He wasn’t a bit embarrassed to be reminded of his outburst.

Mark selling his wares at the 2011 PulpFest.

By 2005 Mark was not only attending Pulpcon each summer, he also was patronizing the Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention every April and New Jersey’s Pulp Adventurecon every November. But being around pulps and pulp aficionados three times a year still wasn’t enough for him. After making inquiries he arranged to commandeer the meeting room at a downtown branch of the New York Public Library for monthly Saturday-afternoon meetings of what he called the Gotham Pulp Collectors Club. The club met for the first time that November. The charter members were Mark, Chris Kalb, Robert Lesser, Leo Doroschenko, and myself. With very few exceptions the group has assembled every month since. It’s gone through several venues and currently meets at the Muhlenberg Library on Manhattan’s West 23rd Street. The membership has grown to nearly two dozen people and roughly half of them are present at any given meeting.

Mark took great pleasure in the Club’s success and longevity, and constantly advocated for new members. In the last year or two, even in fragile health, he looked forward to every meeting—and even more so to the “after-meeting,” which consists of group dining at the local coffee shop. Those sessions are often lively, to say the least. During last month’s meal Mark and I got into a heated argument over politics. But as was always the case following such eruptions, we left the diner with no hard feelings. “See you next month,” Mark called to me as he shuffled up 23rd Street.

This month’s meeting was scheduled for last Saturday, the 21st. As it happens, New York’s libraries are closed to groups like ours due to Coronavirus concerns. But I wouldn’t have seen Mark anyway. He died last Wednesday.

I noted earlier that Mark and I weren’t especially close friends. Occasionally we swapped e-mails between meetings, and on rare occasions one of us phoned the other. I often kidded him, sometimes mercilessly, although he gave as good as he got. But there was never any rancor between us. And when you’ve been sitting next to a guy every third Saturday for 15 years, you get used to him. Mark enjoyed being around pulps and enjoyed being around pulp collectors even more. I’ll miss him.

Mark at the 2017 Windy City convention.

Windy City 2020 Film Program Notes 2

Today we present the program notes for Saturday’s films being shown at this year’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention.

SATURDAY

10:00 am — The Roaring West (1935), Chapters Nine through Fifteen, 140 mins.

Adapted from Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, January 1935).

See above notes for Friday screening of Chapters One through Eight.

12:30 pm — The Hatchet Man (1932), 75 mins.

Adapted from Achmed Abdullah’s “The Hatchetman” (Blue Book, March 1919), also his play The Honorable Mr. Wong.

Let’s make this clear at the outset: If you can accept such obviously Occidental actors as Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Dudley Digges, and Charles Middleton as Chinese inhabitants of San Francisco during an early 20th-century tong war, you’ll probably enjoy this William Wellman-directed drama from Warner Bros. But doing so requires an enormous suspension of disbelief and has proved an insurmountable obstacle for many a viewer. We daresay that was the case upon the film’s initial theatrical release in 1932, which probably accounts for its lackluster box-office performance. Still, there’s much to recommend in The Hatchet Man.

Robinson plays Wong Low Get, the hatchet-wielding dispenser of justice for Frisco’s Lem Sing tong. Forced by his fealty to the tong to kill his own best friend, the member of a rival group, Wong accepts the role of guardian to the latter’s six-year-old daughter Toya San, who grows up to look like Loretta Young. Because the hatchet man has been so kind to her—even though he killed her father, a fact of which she is unaware—Toya believes herself honor bound to accept his proposal of marriage. But her true love is Harry En Sai (Leslie Fenton), a New York-born Chinaman who has come west to join the Lem Sing tong. Their romance is destined to end in tragedy, but we guarantee you’ll be surprised by its exact nature.

The Hatchet Man was an unusual assignment for Wellman, who become a top Hollywood director following the success of his Oscar-winning World War I aviation drama Wings (1927). As a Warners contractee in the early Thirties he specialized in rugged crime thrillers and socially conscious dramas such as Public Enemy (the 1931 gangster film that made James Cagney a star), Night Nurse, Star Witness, Safe in Hell, Love Is a Racket, Heroes for Sale, and Wild Boys of the Road. We’re guessing he chafed under the responsibility of making the anachronistic Hatchet Man marketable to Depression-era moviegoers, but the film benefits from his no-nonsense helming and the uncompromising fatalism that was a Warners trademark during this period.

01:45 pm — The Human Monster (aka Dark Eyes of London, 1939), 73 mins.

Adapted from Edgar Wallace’s “Blind Men” (Detective Story Magazine, May 7—June 4, 1921), later published in hardcover as Dark Eyes of London.

A spine-tingling Edgar Wallace adaptation that was filmed in London but traded on the conventions of American horror movies, Dark Eyes of London is notable as the first British film awarded an “H” certificate (identifying a “Horrific” movie to which only those over the age of 16 could be admitted). While certainly tasteless, this Argyle Productions shocker wasn’t far removed from its Hollywood counterparts. In choosing Bela Lugosi as the film’s lead villain, producer John Argyle clearly intended his modestly budgeted Wallace adaptation to emulate American-made chillers. Indeed, Dark Eyes is comparable to the “B”-grade product Bela would soon be making for such low-rent Tinseltown outfits as Monogram and PRC.

Polite, kindly Dr. Orloff (Lugosi) heads the Greenwich Insurance company and funds a home for the blind run by coolly efficient Mrs. Reaborn (May Hallatt). But when a series of murders are linked to the charitable institution, Scotland Yard Inspector Larry Holt (Hugh Williams) and recently orphaned Diana Stuart (Greta Gynt) launch a discreet investigation that finds the young woman taking a job at the home. Suspicion lands on a bestial resident named Jake (Wilfrid Walter), although Larry believes a master mind is behind the killings.

Although British citizen Edgar Wallace enjoyed his greatest success in the United Kingdom, his thrillers were nearly as popular in America. Many of them, including “Blind Men,” saw publication in Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine prior to issuance in hard covers. Nearly all took place in Merry Olde England (and frequently were confined to London), so it’s no surprise that Brit filmmakers licensed them for translation to celluloid. During the Thirties alone more than two dozen Wallace properties reached U.K. theater screens, with another half dozen being dramatized late in the decade for experimental television broadcasts by the BBC.

Our DVD of Dark Eyes derives from a transfer of the American theatrical version, retitled The Human Monster and released here by Monogram Pictures in early 1940.

03:00 pm — Convicted (1938), 58 mins.

Adapted from Cornell Woolrich’s “Face Work” (aka “Angel Face,” Black Mask, October 1937).

The first Cornell Woolrich story to reach the screen was Children of the Ritz, a College Humor novelette adapted by Warner Brothers in 1929. But this unpretentious Columbia “B” picture was the first to adapt one of his suspenseful crime stories from the pulps. It was produced in Canada (with studio funding) under the auspices of Kenneth J. Bishop’s Central Films Ltd. Shot over a two-week period in December 1937, Convicted was directed by Leon Barsha and reunited 19-year-old starlet Rita Hayworth with handsome Charles Quigley, with whom she had already been paired in several low-budget melodramas.

Woolrich’s heroine, one Jerry Wheeler, is a street-wise stripper who turns detective to prove that her kid brother Chick has been framed for the murder of gold-digging Ruby Rose. Not surprisingly, Jerry became a nightclub dancer in the film version, which otherwise sticks closely to “Face Work,” even to incorporating much of Woolrich’s dialogue.

Hayworth was actually too young for her role; actor-screenwriter Edgar Edwards, who played Chick, was several years her senior. But even at this early stage in her career Rita exhibited star quality and easily outclassed wooden leading man Quigley. Prolific screen heavy Marc Lawrence, just beginning a lengthy career, delivers the film’s best performance, although his comeuppance is a bit too abrupt to be wholly satisfying.

We make no claims of greatness for Convicted. Cheaply made, intended for the bottom half of a double bill, and produced in Canada under an arcane quota requirement of Hollywood studios marketing product to the United Kingdom, it’s primarily of historical interest to pulp fans. Including the picture in this year’s Windy City lineup acknowledges two anniversaries: the Black Mask centennial and the 20th anniversary of our convention. Convicted was among the movies screened in our very first film program. Back then we were running 16mm prints exclusively. The DVD we’re showing this year is a recent high-definition video transfer made from original 35mm elements in the studio’s vault. As yet it has not been made commercially available for purchase.

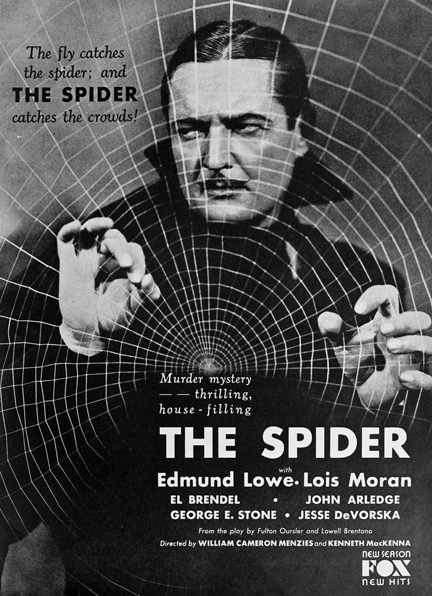

04:00 pm — The Spider (1931), 59 mins.

Adapted from Grace Oursler’s “The Spider” (Ghost Stories, December 1928—July 1929), a novelization of the 1927 play by Fulton Oursler and Lowell Brentano.

Like The Sin of Nora Moran, which we showed here last year, The Spider has a convoluted literary history. The basic plot was devised for “The Man with the Miracle Mind,” serialized in four late 1921 issues of National Pictorial Brain Power Monthly, a magazine published by physical-culture enthusiast Bernarr Macfadden. Authorship was attributed to one Samri Frikell, a pseudonym used by Fulton Oursler, who edited and contributed to various Macfadden sheets.

In 1927 Oursler and author/playwright Lowell Brentano dramatized the story as The Spider, a play that opened on Broadway in March 1927. A true novelty, it was a murder mystery that took place in a New York vaudeville house, which was represented by the theater staging the play (Chanin’s 46th Street Theatre from March to May, then the Music Box until the show’s December 17 closing). Actors playing the chief suspects were thus scattered throughout the first few rows, near the orchestra. Once the murder had been committed, actors playing police ran down the aisles shouting that nobody could leave the theater while the investigation was underway. It was a fascinating gimmick that inspired favorable word-of-mouth and enabled the show to sell out 319 performances in its first run. (A 1928 revival in the Century Theatre inexplicably lasted just two weeks.)

Following the Broadway engagements, the play was novelized by Oursler’s wife Grace and—not surprisingly—slated for publication in a Macfadden-owned pulp magazine, Ghost Stories, running as a serial from December 1928 through July 1929. Screen rights to both play and novel were then sold to the Fox Film Corporation for $27,500. The Spider was assigned to a new directorial team, former actor Kenneth MacKenna and well-regarded scenic designer and visual-effects specialist William Cameron Menzies. The latter eagerly accepted the challenge of making a magician’s stage illusions spectacularly cinematic. Art director Gordon Wiles, meanwhile, designed elaborate sets to represent the entire theater—the stage, the auditorium and orchestra pit, dressing rooms, and a prop-filled basement. Award-winning cinematographer James Wong Howe, working from Menzies’ detailed sketches, devised atmospheric lighting effects to reflect the director’s vision. Principal photography began on June 11, 1931 and consumed just three weeks. Menzies and company had prepared thoroughly.

The plot revolves around a magician and mentalist named Chatrand the Great (played in the film by Edmund Lowe), whose emotionally fragile assistant Alexander (Howard Phillips) has genuine psychic abilities and participates in a mind-reading act that’s the highlight of Chatrand’s nightly show. Alexander suffers from amnesia, and each evening Chatrand broadcasts from the stage an appeal for information to the young man’s identity. Hearing the psychic’s voice over the radio, Beverly Lane (Lois Moran) becomes convinced that he is her brother, driven from his home long ago by their cruel stepfather, John Carrington (Earle Foxe). She persuades the reluctant Carrington to bring her to Chatrand’s next show, and he is murdered when theater lights are extinguished during the performance. Alexander is suspected of the crime and Chatrand uses his assistant’s psychic talents to help ferret out the real killer.

The film cost $311,517, a fairly substantial amount for a glorified “B” picture. It earned worldwide film rentals totaling $519,137. Subtracting distribution costs, it returned a modest profit of $16,052 to Fox. Grosset & Dunlap published a hardcover “PhotoPlay” edition of Grace Oursler’s novelization.

The Spider is heavy on visual appeal but light on plot. It also lacks the key element of the stage play’s appeal: Broadway audiences were part of the action, but moviegoers were just spectators. Nonetheless, it’s an extremely entertaining film and, at just 59 minutes, too compact to be boring. It was also a good warm-up for the following year’s Chandu the Magician, another mysticism-heavy melodrama starring Lowe, photographed by Howe, and co-directed by Menzies (this time with Marcel Varnel). By the way, Lowe’s Chatrand must have been the model for the comic-strip character Mandrake the Magician, who first appeared in newspapers three years after The Spider‘s release. See the movie and decide for yourself.

Immediately Following Auction — Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937), 53 mins.

Adapted from William Colt MacDonald’s “Riders of the Whistling Skull” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, March 1934) and “Valley of the Scorpions” (Big-Book Western Magazine, November 1934).

Next to Clarence Mulford’s Hopalong Cassidy, featured in 66 feature-length movies produced between 1935 and 1948, the most popular Western-pulp characters to grace the silver screen were William Colt MacDonald’s Three Mesquiteers: Tucson Smith, Stony Brooke, and Lullaby Joslin. They were featured (with occasional substitutions) in 55 films made between 1935 and 1943; all but two of these emanated from Republic Pictures, the small studio that also was home to Gene Autry and Roy Rogers.

MacDonald introduced Tucson and Stony in “Restless Guns,” a book-length yarn serialized in late 1928 issues of the Clayton pulp Ace-High Magazine. They were joined by Lullaby at the end of “The Law of the Forty-Fives,” serialized in the December 1929—April 1930 issues of Harold Hersey’s Quick-Trigger Western Magazine. That yarn was the first Mesquiteer story to reach the screen, produced in 1934 with Guinn “Big Boy” Williams as Tucson and comedian Al St. John as Stony (whose last name was inexplicably changed to Martin). Williams then played Lullaby in Powdersmoke Range (1935 RKO) opposite Harry Carey’s Tucson and Hoot Gibson’s Stony.

Republic’s series began in 1936 with The Three Mesquiteers, which cast little-known actors Ray “Crash” Corrigan as Tucson and Bob Livingston as Stony. Painfully unfunny comedian Syd Saylor played Lullaby for this entry only; the next film, Ghost Town Gold, replaced him with old-time vaudevillian and radio performer Max Terhune.

Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937), Republic’s fourth Mesquiteers opus, was the best to date. The screenplay by Oliver Drake and John Rathmell combined plot elements from two MacDonald novels, “Whistling Skull” and its successor, “Valley of the Scorpions” (published in hard covers as The Singing Scorpion).

The film is suffused with mystery and includes a dollop of horror to chill the blood. It opens with the Mesquiteers joining an archaeological expedition searching for the lost city of Lukachukai, home to descendants of an ancient Indian murder cult known as the Sons of Anatazia. One of the scientists has just been murdered, and detective-story enthusiast Stony is eager to find the killer. While searching for the lost city’s landmark—a huge rock formation in the shape of a human skull—the expedition is menaced by raiders from the lost city. The Mesquiteers learn that the man behind these depredations is a member of their party.

Riders of the Whistling Skull offers a refreshing departure from horse-opera formula. There are no cattle rustlers, stagecoach robbers, crooked bankers, or dictatorial ranchers. No stampedes, no saloon brawls, no street duels at high noon. Instead there’s genuine mystery and steadily building suspense. Competent but undistinguished director Mack V. Wright fails to fully exploit the script’s possibilities—it indicates a spooky atmosphere he never really develops—yet Riders succeeds primarily by virtue of its novelty. At 53 minutes it’s short and fast-moving . . . just what you’ll crave after a lengthy auction!

Windy City 2020 Film Program Notes 1

At each year’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention, Murania Press sponsors a film program that concentrates exclusively on movies adapted from stories originally published in pulp magazines. This is the con’s 20th year, and the 19th for our film screenings. Below are program notes describing the Friday offerings; tomorrow we’ll post notes covering Saturday’s selection.

FRIDAY

12:00 pm — The Roaring West (1935), Chapters One through Eight, 160 mins.

Adapted from Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, January 1935).

Buck Jones, who had been a Western star for 15 years when he made Roaring West, was also an avid reader of pulp fiction. During his 1934-37 tenure at Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures, Buck had his own production unit and personally selected the stories for his starring vehicles. The vast majority were yarns first published in rough-paper magazines. We have not read Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law,” the credited source for The Roaring West, and therefore can’t comment on the serial’s degree of fidelity to the original story. But very few novels had plots dense enough to fill 15 two-reel episodes, and it’s obvious that screenwriters George H. Plympton, Nate Gatzert, Basil Dickey, Robert Rothafel, and Ella O’Neill added numerous capture-and-escape sequences to pad the proceedings.

Jones plays Montana Larkin, a two-fisted cowboy who helps his pal Jinglebob Morgan (Frank McGlynn Sr.) rescue the latter’s brother Clem (Harlan Knight) from claim jumpers led by Gil Gillespie (Walter Miller). The bad guys are eager to learn the location of Morgan’s gold mine. Montana’s allies include prominent rancher Jim Parker (William Desmond) and his daughter Mary (Muriel Evans).

Some Windy City viewers might find Roaring West unnecessarily repetitive, although it should be remembered that serial chapters were designed to be seen at the rate of one per week, not bunched together in groups of seven or eight per day. But the chapter play’s plot deficiencies are compensated for by a wealth of fast action and Buck’s endearing performance. He’s especially good in scenes with Muriel Evans, his favorite leading lady, who also appeared in six of his self-produced feature films. Their chemistry is palpable and authentic; when I met Muriel in 1990 and asked her about Jones, she described him as “one of God’s great gentlemen.”

At the time of this serial’s production Buck Jones was the nation’s top cowboy star, a favorite of exhibitors and hero to millions of American boys. The Roaring West isn’t the best of his motion pictures by a long shot, but it’s representative of his peak-period output and rollicking good fun even today, 85 years after its theatrical release. We can guarantee that it won’t tax your brain, so if looking to take a break from the dealer room’s hustle and bustle, you could do a lot worse than to relax by watching a few chapters.

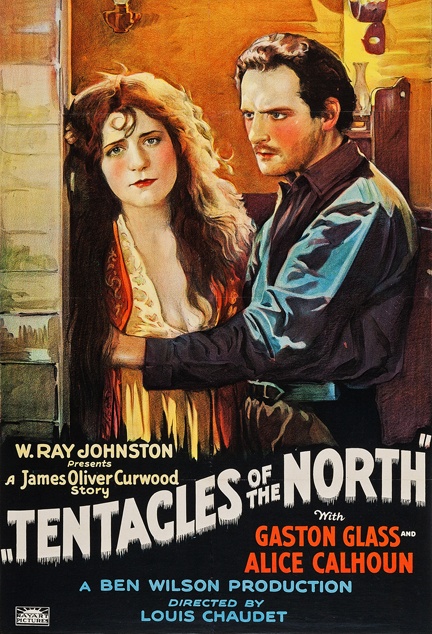

02:45 pm — Tentacles of the North (1926), 52 mins.

Adapted from James Oliver Curwood’s “In the Tentacles of the North” (Blue Book, January 1915).

Few fictioneers ever attained the success enjoyed by James Oliver Curwood, who wrote for slicks and pulps alike and saw many of his best tales published between hard covers. His virile adventure stories, mostly taking place in Alaska and the Canadian Northwest, were extremely popular with filmmakers, who began licensing them in 1910 and adapted them to the screen regularly for the next 50 years. Some Curwood yarns, including River’s End, The Wolf Hunters, and Back to God’s Country, were made into movies three and four times each. For many years, especially during the Twenties and Thirties, his name on a movie poster virtually guaranteed an audience regardless of the film’s quality.

This low-budget thriller, while hardly among the best Curwood-based movies, is certainly typical of the breed. A terse synopsis from Motion Picture News captures its essence nicely: “Ice in North seas ties up two vessels; one with boy mate and other with daughter of seaman left alone through death of crew. Boy leaves his ship and discovers girl. He is chased by his crew but outwits them and escapes both them and the Arctic wastes. He brings girl back to civilization.”

Produced by Poverty Row habitué Ben Wilson, Tentacles of the North hews closely to the Blue Book yarn on which it’s based and seems to have pleased the undiscriminating small-town audiences for which it was intended. The unabashed melodrama wasn’t very well received by big-city sophisticates, though. Variety‘s critic “Mark” (no last name given), reviewing the picture after a screening in Manhattan, was decidedly unimpressed: “It may have been the intention to make this Curwood [adaptation] a big production, but it pulled a smashing dud, face down. Little to commend it despite the apparent camera effort to make the far, far northland, but the icy, frigid scenes won’t. [sic] The New York audience didn’t think much of it. Some of them sighed when the end came. One wonders if Mr. Curwood could recognize in this production any of the realistic scenes his book [sic] describes.”

On the plus side, we are showing a privately pressed DVD mastered from an original tinted 35mm nitrate print of Tentacles. As always with the silent movies we include in our Windy City film program, it’s accompanied by a period-appropriate music score.

03:45 pm — The Working Man (1933), 75 mins.

Adapted from Edgar Franklin’s “The Adopted Father” (All-Story Weekly, January 22—February 19, 1916).

Totally forgotten by even the most rabid fans and collectors of pulp magazines, Edgar Franklin (real name: Edgar Franklin Stearns) for many years was a ubiquitous presence in the Munsey sheets—Argosy, Cavalier, All-Story, Scrap Book, Railroad Man’s Magazine—and sold frequently to other general-interest pulps such as People’s, Blue Book, and The Popular Magazine. His work also appeared regularly in such prestigious slicks as Red Book, Hearst’s Cosmopolitan, and the mighty Saturday Evening Post. So why is Franklin so little known today? Mostly because he specialized in humorous tales with domestic settings and not gun-dummy Westerns, lost-race adventures, or masked-hero melodramas—in other words, not the types of stories favored by most present-day collectors.

Franklin’s stories were licensed by Hollywood studios some 32 times between 1914 and 1938, although elements from the best were “borrowed” rather promiscuously by scripters cranking out purportedly original screenplays. His 1916 book-length comedy-romance “The Adopted Father” was filmed three times: in 1924 as $20 a Week, in 1933 as The Working Man, and finally in 1936 as Everybody’s Old Man. The first two versions starred stage actor George Arliss, a horse-faced ham who reinvigorated his film career with a series of well-regarded early-Thirties biopics that cast him as Voltaire, Disraeli, Cardinal Richelieu, Alexander Hamilton, and the Duke of Wellington. A scenery-chewer of the first water, Arliss occasionally eschewed heavy historical fare in favor of lighthearted contemporary tales that permitted him to portray avuncular characters.

The Working Man casts Arliss as wealthy shoe manufacturer John Reeves, who leaves his business in the hands of ambitious nephew Benjamin Burnett (Hardie Albright) and goes to Maine on a fishing trip. While up there Reeves meets Tommy and Jenny Hartland (Theodore Newton and Bette Davis), the fully grown but undisciplined children of his friendly rival, the late Tom Hartland. Distressed by their cavalier handling of the family business, Reeves has himself appointed a trustee of the Hartland estate. He insinuates himself into the lives of Tommy and Jenny—who don’t know his true identity—and persuades them to take greater interest in the venerable firm that is their father’s legacy. Jenny becomes sufficiently competitive to secure a job at the Reeves Company under an assumed name, but she doesn’t count on falling in love with John’s nephew Benjamin. As the saying goes, complications ensue.

Working under his favorite director, John G. Adolfi, Arliss turns in a delightful performance. Bette Davis, still a year away from her star-making turn in Of Human Bondage (1934), is appropriately spirited as Jenny Hartland; it’s hard to imagine that Working Man audiences wouldn’t have recognized the obvious talent that would soon make her one of the biggest names in the picture business. Fast-faced and funny, this Warner Bros. programmer is easily the best adaptation of Franklin’s thrice-filmed 1916 pulp story.

Immediately Following Auction — Lawless Valley (1938), 59 mins.

Adapted from W. C. Tuttle’s “No Law in Shadow Valley” (Argosy, September 26, 1936).

A phenomenally prolific pulpster whose Westerns appeared in rough-paper magazines for more than 40 years, Tuttle also enjoyed considerable success in Hollywood. Movie rights to his yarns were being snapped up by studios as early as 1920, and during the silent-film era he penned original screen stories for such popular cowboy stars as Hoot Gibson. One of his pulp tales, “Sir Piegan Passes,” was adapted by filmmakers three times.

Tuttle’s 1936 novelette “No Law in Shadow Valley” was licensed early in 1938 by RKO, at that time on the lookout for properties that would make suitable vehicles for its newest Western star, George O’Brien. No stranger to horse operas adapted from pulp stories, O’Brien at Fox Film Corporation during the early Thirties had top-lined sturdily made Westerns based on popular yarns by Zane Grey and Max Brand. Budgets routinely approached $200,000 and funded lengthy sojourns to picturesque locations in Arizona, Colorado, and Utah.

O’Brien’s RKO series, however, was produced on a more modest scale. Lawless Valley, which opened the 1938-39 season, cost exactly $80,364 with exteriors lensed in familiar Southern California locations and on the Western street in the studio’s Encino facility. A strong entry, it has a dialogue-heavy first act but picks up the pace considerably about 30 minutes in, finishing with the knuckle-bruising action that audiences had come to expect from George’s pictures. The brawny star plays an ex-con who returns to his home range to apprehend the men responsible for killing his father and framing him into prison. Forbidden from carrying a gun by the terms of his parole, O’Brien’s character is forced to rely on his wits to expose the real culprits.

In a nice bit of casting, veteran heavy Fred Kohler and his son Fred Jr. play a crooked father and his offspring. Chill Wills, rail-thin at this early stage in his film career, interprets a familiar Tuttle character type: the lanky, disrespectful deputy who’s forever needling a blustery sheriff. Erstwhile silent-serial leading man Walter Miller contributes a solid supporting turn as a tramp who befriends O’Brien after the latter is released from prison.

Nobody will ever mistake Lawless Valley for Shane, Stagecoach, or The Searchers. It’s a Saturday-matinee “B” Western, plain and simple, but a first rate example of the species. If you’re not expecting too much we think you’ll thoroughly enjoy this encore presentation from our 2002 lineup.

McCulley Omnibus Price Reduction

Exactly one year ago today Murania Press released this 502-page omnibus of Johnston McCulley novels reprinted from the pages of Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. To mark the anniversary we are permanently reducing the price of this jumbo-sized volume to $25, which includes shipping to domestic U.S. buyers. For more information and easy ordering, just click on this link: https://muraniapress.com/book/johnston-mcculley-omnibus/

Now Available: A Scintillating Slice of Serial History

The complete story of Walter Miller and Allene Ray, king and queen of the silent serial. Beautiful, blonde Allene had already starred in three chapter plays for Pathé Exchange, Inc., when the firm teamed her with handsome, virile Walter in early 1925. Their first starring serial, Sunken Silver, was based on an Albert Payson Terhune novel adapted to the screen by ace scripter Frank Leon Smith. Directed by George B. Seitz with an assist by Spencer Gordon Bennet, it proved successful beyond expectations. With the glory days of episodic epics receding into history, Pathé was delighted to keep the pair together. Although Seitz left serials to direct features at Paramount and other studios, the Miller-Ray unit continued to function with Bennet promoted to full director and Smith providing the scenarios.

This group collaborated on nine more serials released by Pathé over the next four years. While some were better than others, the overall average was remarkably high. Among the very best were The Green Archer (1925, adapted from the classic mystery yarn by best-selling British mystery writer Edgar Wallace) and The House Without a Key (1926, adapted from Earl Derr Biggers’ first Charlie Chan novel). With a total of ten chapter plays to their credit, Miller and Ray were the most prolific team in the history of the form. To further exploit their popularity, Pathé occasionally featured each with other co-stars; Allene Ray would ultimately take the female lead in 16 chapter plays—more than any other actress. Miller notched 17 serials as leading man and at least a dozen more (in the sound era) as a villain. Director Bennet, having early on displayed his affinity for the genre, ultimately helmed some 53 episodic thrillers, including 1956’s Blazing the Overland Trail, the final serial produced for the theatrical market in America.

Partners in Peril, expanding upon material originally published in two Blood ‘n’ Thunder articles and the book Distressed Damsels and Masked Marauders, covers the Miller-Ray serials in exhaustive detail. Its exclusive sources include the private correspondence of Frank Leon Smith, several interviews with Spencer Bennet, and surviving copies of the original scripts to half of the team’s chapter plays. Additionally, this monograph features dozens of rare photos—including on-the-set candids—that became available to me only after publication of the BnT articles and Distressed Damsels.

For anybody interested in the silent-movie era in general and the classic cliffhangers in particular, Partners in Peril will not just provide hours of entertainment but also become a valuable reference to which you’ll return again and again.

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net