EDitorial Comments

2018 Windy City Film Program

As always, this year’s Windy City Pulp and Paperback Convention film program boasts a number of obscure motion pictures adapted from pulp stories. There’s often an exception, though, and this year it’s The Keep (1983), based on the novel by special guest F. Paul Wilson, who will be on hand for the screening. Also as always, the film program is sponsored, assembled, and presented by Murania Press and Blood ’n’ Thunder. If you plan on attending the convention, here’s what you can expect. If not, here’s what you’ll be missing….

FRIDAY

12 p.m. — They Came from Beyond Space (1967).

Adapted from “The Gods Hate Kansas” (Startling Stories, November 1941) by Joseph Millard.

This British-made SF offering is decidedly cheesy but pleasantly old-fashioned in its approach. An Amicus production written by the company’s co-founder, Milton Subotsky, and directed by genre specialist Freddie Francis (who worked simultaneously on horror/SF films for Amicus and Hammer), They Came from Beyond Space takes place in rural England. Scientists descend upon a farm field to investigate a shower of small meteorites that landed in a V formation, suggesting an intelligent design. American actor Robert Hutton, a once-promising performer who landed a contract with Warner Brothers but failed to catch fire with the public and drifted into TV during the Fifties, stars as Dr. Curtis Temple, forbidden from joining his colleagues because he’s still recovering from injuries sustained in a car accident. Just as well: the investigating scientists, including Temple’s girlfriend Lee Mason (Jennifer Jayne), are possessed by an alien life force and turned into robotic slaves working upon behalf of the extraterrestrials. He finally goes to the remote camp but seems immune to whatever it is that now controls Lee and their co-workers. Why? And can he use this immunity to rescue his friends?

Those are the burning questions ultimately answered by director Francis and company in 85 minutes of low-budget foolishness. They Came from Beyond Space is a minor and curious addition to the roster of films adapted from pulp stories; we can’t honestly say you’d be missing a forgotten gem if you choose to pass it up and spend the convention’s first hour and a half in the dealer’s room. But it has a measure of charm, to be sure, and if you look carefully among the supporting players you’ll see Michael Gough, whose later screen accomplishments included playing Alfred the butler in the Batman movies starring Michael Keaton.

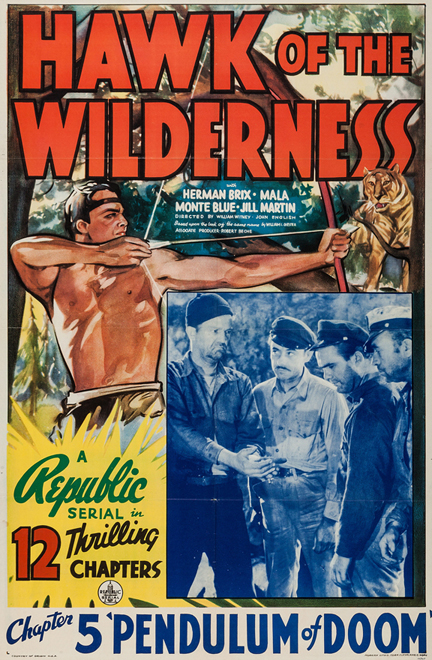

1:30 p.m. — Hawk of the Wilderness (1938).

Adapted from “Hawk of the Wilderness” (Blue Book, April-October 1935) by William L. Chester.

Of all the imitation Tarzans who paraded through pulp pages in the wake of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ immortal ape man, William L. Chester’s Kioga the Snow Hawk was possibly the best. Chester came from out of nowhere, with no previous fiction-writing credits, and sent his first novel, Hawk of the Wilderness, to Blue Book editor Donald Kennicott. It was accepted with alacrity, serialized during 1935, and published in hard covers by Harper & Brothers the next year. Chester wrote three sequels for Blue Book, which serialized one a year for 1936, 1937, and 1938. After selling an isolated short to Adventure, he apparently gave up writing fiction—and the pulp world lost a talented storyteller.

Republic Pictures licensed the first Kioga yarn upon its publication by Harper in 1936. Chester’s novel was entrusted to the serial unit for adaptation. For reasons unknown, however, a workable script wasn’t completed until 1938. The studio then cast Herman Brix, an Olympic athlete and former screen Tarzan, as the Snow Hawk; he had previously taken prominent roles in two other 1938 chapter plays for Republic, The Lone Ranger and The Fighting Devil Dogs. Both were directed by the formidable team of William Witney and John English, who had evolved a style of action filmmaking that would result in an unbroken string of successful serials regarded by aficionados of the form as among the best ever made.

Hawk of the Wilderness was shot in less than a month, with the dense forests near California’s Mammoth Lakes standing in for the uncharted volcanic island Chester placed in the Arctic Circle. As might have been expected, Republic’s screenwriters took liberties with the original work (such as elevating a minor character named Solerno to chief villain) but maintained fidelity to the basic concept. Brix was more than qualified to handle such daring physical feats as the script demanded, and he did his share of tree-swinging in Tarzan fashion. Hawk is a fine serial, beautifully photographed and loaded with action. It’s marred only by some unfortunate, stereotypical “comedy relief” from an African-American actor billed as “Snowflake.”

3:30 p.m. — The Keep (1983).

Adapted from the novel by F. Paul Wilson.

The Windy City film program occasionally deviates from its stated mission to offer only obscure movies adapted from stories that originally appeared in pulps. This year’s exception is being made in deference to our guest star, F. Paul Wilson, whose Repairman Jack novels are very much in the pulp tradition, being fast-action thrillers with supernatural underpinnings. The Keep, published in 1981, was his first horror story. Two years later it was brought to the screen by Michael Mann, who not only penned the adaptation but directed the film as well.

The story takes place during World War II, with Nazi soldiers and commandos being killed off in a mysterious castle in the Carpathian Mountains. It appears that some ancient demonic force within the fortress walls has been unleashed, and Nazi commander Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne) eventually—and ironically—calls upon an eminent Jewish scholar, Dr. Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellen), to identify and help defeat the malevolent entity. The presence of an enigmatic man named Glaeken (Scott Glenn) may have something to do with his problem.

Although The Keep was both a critical and commercial flop upon its theatrical release, but with subsequent exposure on TV and video the film has become a cult favorite in certain precincts. Wilson himself once described it as “visually intriguing, but otherwise utterly incomprehensible.” He’ll be on hand for our screening and is expected to make additional comments. Trust us, you’ll want to be there.

Immediately following evening auction — The Devil’s Saddle Legion (1937).

Adapted from “Hell’s Saddle Legion” (Big-Book Western, November-December 1936) by Ed Earl Repp.

The ninth of Dick Foran’s 12 “B” Westerns for Warner Brothers is a pretty fair horse opera, not as good as some of his earlier ones but certainly better than the three to come. Produced for approximately $64,000—a meager outlay for a major studio, even in those Depression days—The Devil’s Saddle Legion returned $158,000 in film rental (the fees paid by exhibitors). With studio overhead, distribution costs, and advertising and promotional expenses subtracted, it returned a tidy $34,500 net profit to Warners. That doesn’t sound like much in today’s world of billion-dollar blockbusters, but those “B”-picture profits made up for a lot of many rarified “A” movies that lost money.

During the 1880s, the region bordered by the Red River is claimed by both Texas and the wild and woolly Oklahoma Territory. Tal Holloway (Foran) has just returned to Texas when he witnesses the murder of a family friend. Arrested by a crooked sheriff, Tal winds up in a prison camp whose inmates are providing slave labor for a big project: the building of a dam that would change the Red River’s course and allow corrupt Hub Ordley (Willard Parker) to claim additional land for Oklahoma. Can Tal escape from the camp and clear his name?

A burly redhead from New Jersey, Foran was also a baritone who signed with Warner Brothers just as a young upstart named Gene Autry was commencing his series of musical Westerns for Republic Pictures. Warner’s “B”-picture production head Bryan Foy had writers hastily retool their script for an oater called Boss of the Bar-B Ranch, inserting several songs and retitling it Moonlight on the Prairie. Thus Dick Foran, a most unlikely Western star, became the screen’s second singing cowboy. He occasionally appeared in Warner “A” pictures, most notably The Petrified Forest (1936), but he never attained real stardom and eventually drifted to other studios after his Warner Brothers contract expired, always mired in low-budget fare. But he maintained a high average in these little sagebrush sagas, and The Devil’s Saddle Legion is quite entertaining.

SATURDAY

10 a.m. — The Ice Flood (1926)

Adapted from “The Brute Breaker” (All-Story Weekly, August 10, 1918) by Johnston McCulley.

Zorro’s creator was a prolific contributor to the Munsey pulp chain long before he wrote “The Curse of Capistrano” for All-Story Weekly; he placed stories with The Argosy back in 1907 and within five years was selling to The Cavalier, The Scrap Book, and The Railroad Man’s Magazine. (His byline could also be seen regularly in pulps published by other companies, including Blue Book, Top-Notch, and Adventure.) But it was the success of “Capistrano,” licensed for the screen by Douglas Fairbanks and released as The Mark of Zorro, that brought his other work to the attention of Hollywood. Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures did not often purchase screen rights to pulp-magazine stories, but the company bought McCulley’s “The Brute Breaker” sometime in the early Twenties only to sit on it for several years. When produced in 1926

Recent Oxford graduate Jack De Quincy (Kenneth Harlan), scion of a lumber magnate, is dispatched by his father to the northwest to “clean up” a few camps whose output is falling due to raucous behavior, insufficient discipline, and ineffectual management. Working undercover, without any outside help, Jack uses his fists as well as his brains to establish a reputation as a wildcat. He manages to run afoul of pretty Marie O’Neill (Viola Dana), a superintendent’s daughter, but also identifies two bullies as bootleggers operating their racket from one of the camps.

A vigorous action melodrama that climaxes with Jack’s rescue of Marie from gathering ice floes on the frozen river, The Ice Flood turned out much better than anyone at Universal anticipated. Possibly the muscular direction of George B. Seitz, a no-nonsense helmer whose experience dated back to Pearl White serials of the Teens, had much to do with the picture’s reaction. Laemmle insisted the picture be released as a “Universal Jewel,” a designation usually reserved for the company’s biggest productions. Critics were somewhat less impressed, and the picture did only modest business. But it’s a fine film of its type, very much the type of movie we enjoy introducing to pulp fans here at Windy City.

11:15 a.m. — The Flying Squad (1940).

Adapted from “The Flying Squad” (Detective Story Magazine, November 3-December 8, 1928) by Edgar Wallace.

The staggeringly prolific Wallace had already created the Four Just Men and Sanders of the River by the time he began selling thrillers to such American pulps as Flynn’s, The Popular Magazine, and Detective Story Magazine. The latter serialized no less than two dozen of his novels, beginning with Jack o’ Judgment in 1920. Th Flying Squad appeared in that long-running Street & Smith pulp prior to being issued in cloth by Doubleday as one of its Crime Club selections.

Scotland Yard Inspector Bradley (a young and handsome Sebastian Shaw, unmasked as the dying Darth Vader in Return of the Jedi) is slowly but surely closing in on a smuggling ring headed by suave Mark McGill (Jack Hawkins), who concocts a scheme to throw Bradley off his trail. Having murdered one of his henchmen, McGill tells the dead man’s sister, Ann Perryman (Phyllis Brooks), that Bradley was responsible for her brother’s death by shooting. In her grief, Ann allows herself to be drawn into McGill’s orbit out of a desire for revenge on Scotland Yard and Bradley in particular.

The Flying Squad was the last motion picture directed by Herbert Brenon, a veteran of nickelodeon-era filmmaking whose most famous works included A Daughter of the Gods (1916), Peter Pan (1925), A Kiss for Cinderella (1926), and Beau Geste (1926). Brenon seemed out of sorts in Hollywood once talking pictures became the rage, and relocated in England in 1934. His handling of The Flying Squad, which very much resembles a conventional American “B” picture, is smooth and assured. It marked a pleasant diversion for Phyllis Brooks, the only American cast member, then at liberty following several years as a Fox contract player. (Brooks today is remembered, if at all, as a longtime paramour of Cary Grant.) In a key supporting role is Ludwig Stossel, who later emigrated to America, settled in Hollywood, and finished out his career as the “Little Ole Wine Maker” in TV commercials. But it’s Basil Radford, best known as half of the Charters and Caldicott duo from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes and Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich, who nearly steals the show as a ham actor and petty crook pressed into service by Inspector Bradley.

12:30 p.m. — The Return of Casey Jones (1933).

Adapted from “The Return of Casey Jones” (Railroad Stories, April 1933) by John Patrick Johns.

This Poverty Row production was already underway when the story on which it was based appeared in Railroad Stories. In fact, a cover blurb alerted readers that a celluloid version of the John Patrick Johns short story would soon hit theater screens. We don’t know how or why this occurred; such things had happened before but were very rare. Johns was a specialist in this tiny sub-genre; he wrote exclusively for Railroad Stories and its later incarnation, Railroad Magazine.

Casey Jones, of course, was a real-life railroad engineer who in April 1900 sacrificed his own life to save passengers and other crew members. Knowing that his train was certain to crash into a stalled freight train on a Mississippi track, Casey remained in the cab, rather than jump off, in a successful bid to slow the locomotive. He was the only fatality, and his heroic deed became the stuff of legend. The Return of Casey Jones features Dartmouth football player and future cowboy star Charles Starrett as Jimmy Martin, an engineer wrongly pegged as a coward when he slips and falls from a train just before it hurtles over a precipice. He is thought to have jumped rather than attempt to slow the engine. He becomes a pariah, and his heartbroken girlfriend Nona (Ruth Hall) gives him up for a soldier, “Wild Willy” Bronson (George Walsh). The remainder of the story depicts Jimmy’s attempts to redeem himself.

Entertaining but hardly a world-beater, Return of Casey Jones is typical of the independently produced melodramas that emanated from Hollywood’s smaller studios during the Thirties and Forties. Starrett is a likable leading man, although Hall is such a pallid ingenue that any viewer could have forgiven Jimmy for thinking he was better off without her. Walsh, a silent-screen star originally cast as Ben-Hur in M-G-M’s 1925 classic blockbuster and the brother of director Raoul Walsh, is fine as Starrett’s romantic rival, and the supporting cast is studded with familiar players like Robert Elliott, Jackie Searl, and George Hayes (pre-“Gabby”).

1:45 p.m. — The Whispering Chorus (1918).

Adapted from “The Whispering Chorus” (All-Story Weekly, January 12-January 26, 1918).

Sheehan, a fecund fictioneer whose byline could be seen constantly during the Teens in the Munsey pulps, is undeservedly forgotten today. He worked in several genres and has several classic pieces of fantastic fiction to his credit, including The Copper Princess and The Abyss of Wonders. Screen rights to his novelette “We Are French” (All-Story Cavalier Weekly, August 8, 1914) were purchased by Universal, whose 1916 adaptation of the yarn, The Bugler of Algiers, was one of the most profitable feature films released by the company up to that time. Director Cecil B. DeMille loved Whispering Chorus and urged his partner, producer Jesse L. Lasky, to license it from Munsey. Then he assigned the lead role to Raymond Hatton, at that time one of his stock company but later best known as a Western sidekick.

Having embezzled a large sum of money from his firm, John Trimble (Hatton) decides to abandon his wife and mother. Temporarily hiding on an island off shore, he changes clothes with a corpse and sends the unidentifiable body toward the city waterfront, where it washes up and is believed to be Trimble. The consequences of that act motivate the remainder of the film.

A sober, downbeat drama that DeMille believed would earn him plaudits from all corners, The Whispering Chorus flopped at the nation’s box-offices. The disappointed director never again attempted to do a “message” picture, electing instead to produce films with broad audience appeal. But this is a quality motion picture that illustrates silent-era storytelling at its best and is more highly regarded today than it was upon initial release.

WHISPERING CHORUS: Raymond Hatton and Kathlyn Williams.

3:15 p.m. — Hawk of the Wilderness, Chapters 7-12

Immediately following evening auction — Hopalong Rides Again (1937).

Adapted from “Black Buttes” (Short Stories, November 10-December 25, 1922) by Clarence E. Mulford.

One of the very best Hopalong Cassidy films, this 13th entry in the long-running series actually adapts a non-Hoppy novel by Clarence E. Mulford. Black Buttes, serialized in Short Stories prior to hard-cover publication by Doubleday, has as its protagonist one Wyatt Duncan, whose ten-year search for the man who raped his sister is rewarded when he infiltrates a gang of rustlers headquartered in the forbidding Black Buttes, in which stolen cattle seem to disappear—as do any ranch hands foolish enough to enter this accursed area.

Hopalong Rides Again takes little from the source material but the location of the rustlers’ stomping grounds—the Black Buttes—and the name of the villain, Hepburn. The rest of the story is cut from the series’ familiar pattern, with two important exceptions. First, it gives Hoppy a romantic interest in mature but attractive Nora Blake (Nora Lane); second, it introduces a juvenile cast member in Billy King, a 12-year-old trick rider hired by producer Harry Sherman to give young viewers someone with whom to relate.

The supporting players are those who remain dearest to the hearts of most Hoppy fans: Russell Hayden as hot-headed Lucky Jenkins; George Hayes as grizzled, garrulous Windy Halliday; and silent-serial star William Duncan as rugged old Buck Peters, owner of the fabled Bar-20 ranch. What distinguishes Hopalong Rides Again—in addition to the sturdiness of its deceptively simple plot, the romantic byplay between William Boyd and Nora Lane, and the smoothness of Lesley Selander’s direction—is its inspired use of the Alabama Hills near Lone Pine, California. This picturesque location, used by filmmakers in hundred of movies, is beautifully captured by cinematographer Russell Harlan.

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net